Seductive, Repulsive: Quantum Circus at Soo VAC

Amanda Vail reports on Quantum Circus: The Intelligent Design Process, an enviroment built by Michael Zansky and Andréa Stanislav at the Soo Visual Arts Center. The show is up through December 24.

A faint mechanical whirring, interspersed with periods of unhinged, impish cackling, accompanies entrance into the “Quantum Circus” currently showing at the Soo Visual Arts Center on Lyndale Avenue in Minneapolis. The gallery is dim, thanks to maroon curtains strung across two of the large windows, and the lighting comes across as even more eerie thanks to the subject matter of the exhibition. Situated throughout the front half of the gallery, on the walls and on the floor, are the oddities of Michael Zansky and Andréa Stanislav. Viewers sink neck deep in a tangled web of symbolism, allusion, metaphor, and the just plain peculiar.

The title and presentation say “freak show”; even the curtains (an addition during the first week of the run) contribute by precluding sneak peaks from passersby. The gallery has become a sanctum, the inner space dedicated to the mysteries of any sort of faith, be it religious or secular. Often, those mysteries are intended to awe; sometimes, they disappoint. Zansky and Stanislav intend to illuminate. Or maybe just befuddle. Or maybe just poke a few holes in things so there’s a chance light might shine through.

Scattered throughout are things you might find in a circus: distorted pictures, creepy animals, science experiments gone weird. Glittering white-and-black emaciated hounds gambol atop overturned washbins; monkey busts with ponytails revolve on turntables and fix the viewer with unnerving stares; a cricket in a pink tutu dances madly on the end of gyrating wires. The walls are covered with grotesquely altered portraits, giant astrological charts, and other morphed images. The back half of the sanctum hosts one of Soo’s comfy round benches, suitable for watching the three projected films–and the interaction of viewers with the rest of the gallery pieces.

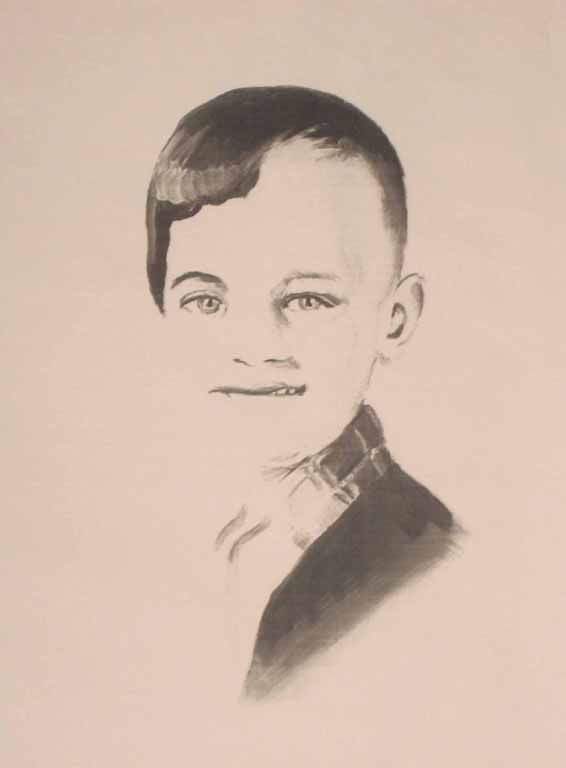

The front half of the south gallery wall is taken up with an enormous collage of images and text entitled Quantum Circus I. Lines lead from one image to the next, connecting them in a network reminiscent of cause and effect, although which is which is not exactly clear. Distorted pictures of dictators, faces squashed in on themselves like a reflection in a house of mirrors, float among mutant, bug-eyed dogs (who also seem to have been subjected to the mirror treatment), trees with glass eyes instead of knotholes, and expanded WWII battle maps covered in Dada and Surrealist imagery. Atop one map, a barely recognizable sideways face melts over Duchamp’s comb.

Quotes from Einstein are peppered throughout the array: “Technological progress is like an axe in the hands of a criminal” or “He who joyfully marches rank and file to music has already earned my contempt. He has been given a large brain by mistake, since for him the spinal cord would suffice.” Other phrases that emerge from the welter of images include “Egypt at her climax,” “The sick man of Europe,” and “Heliogabalus: Wanton, extravagant, depraved, and horribly cruel.” Of particular importance, because they show prominently in other pieces in the exhibition, are “Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream” and “Daniel’s Second Vision: A Bear with Three Ribs in Its Mouth.” The trend by now is obvious: the rise and fall of empires religious, artistic, historical, or otherwise. The stories behind these myriad references lead off on all sorts of tangents; in bringing them together, Zansky and Stanislav attempt to show just how truly unusual the chimera of human experience can be.

Two of the pieces utilize Zanksy’s signature magnifying lenses – Quantum Circus IV, one of the monkey busts, and Quantum Circus VI, the dancing cricket. The lenses make the pieces truly interactive, as the view changes depending upon the perspective of the observer. The light bends about them as the spectator walks past or shifts position; this, combined with the motion of the objects in front of the lenses, is practically dizzying. It is a nod to science, to the voyeurism of a sideshow, and to the ubiquitous critical question of the gaze. How does the viewer’s gaze change the work of art?

In quantum mechanics, that branch of science which has shaped so much of twentieth-century history (see Einstein, Heisenberg, and the atom bomb here), the question of the gaze becomes even more complex: some schools of thought point out that the act of observation changes the nature of the observed, as in the case of Schrödinger’s cat. Is it alive or dead in there? Neither, or both, until the viewer opens the box. If the flashing lights don’t make you lightheaded, thoughts like these certainly will.

In addition to scientific and artistic references there are the religious ones. Daniel’s apocalyptic visions of grotesque animals are paired with Nebuchadnezzar’s dream (also from the Biblical book of Daniel) of a statue representing all the kingdoms of the world, right down to the end times. Which some people presumably still think are upon us. With the heightened state of tension in the world today, it’s hard not to wonder. But if there’s one thing Zansky and Stanislav have made apparent, it’s the patterns of empire, conquest, war, and dictators: in their text, these are horribly frightening and grotesque, but also absurd. One of the three videos in the back shows puppets dancing, rattling mindlessly, to destructive heavy metal music. That the puppets look a little bit like our current President might be only a coincidence; they are also classic caricatures of everyman, with an uncanny grin, big teeth, bulging eyes and protruding ears. These creatures aren’t marching to the beat of their own drum; perhaps for them spinal cord alone really would suffice.

/

A second projected film is a sequence of pictures, beginning and ending with a monkey, showcasing artwork from the exhibition and film clips reminiscent of 1950’s television. In the background, names of influential social figures have been warped into what could either be ticks on a classic timeline or the pulse of an EKG machine. The third film is a lovely, quiet piece, mainly in soft grey tones, that nevertheless manages to disturb through quiet eeriness. Mirror images, the separation and fusing of doubles, and a dose of Zen gardens and Japanese Shinto torii gates, make it mesmerizing; it’s easy to watch three or four times in a row. Music from the dancing puppets film and demonic cackling from the small television on the floor several yards away, however, show the solitude of this piece to be illusory. Quantum Circus is a sculptural environment; the artworks within it cannot be separated from each other and retain the same meaning.

Once one has been submerged in the show, exiting is difficut – it’s seductive in its own way, even though much of the imagery is repulsive. It’s even harder to leave behind completely. Stanislav and Zansky have generated enough food for thought to last a lifetime, simply because so much of it is tied into the way we perceive the world. No loaves and fishes miracles here, though; rather, the artists seem to be teaching fishing techniques. Here’s hoping the observers walk away and catch a big one.