Irreconcilable Differences: The McKnight Fellows Coexist at MCAD

Cecilia Aldarondo reviews the McKnight Fellows Show at MCAD: Suzanne Kosmalski, David Lefkowitz, Aaron Van Dyke, Jay Lance Wittenberg show the work they spent the last year doing.

At a recent panel discussion of the 2006 McKnight Fellows exhibition currently on display at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, LA critic Jan Tumlir attempted to spur the debate by wondering if there was a ‘regional sensibility’ to the show. With a city-mouse naiveté, Tumlir peddled stereotypes of metropolitan v. provincial art as he trawled the artists’ work for literal symptoms of some kind of relentless Midwesternness.

The truth is, the four artists in this exhibition share little, apart from the fact that they have all received $25,000 grants from the McKnight Foundation, which supports mid-career Minnesota artists through its annual competition. But while Tumlir may have been off the mark in trying to nail these artists so directly to their home turf, the question of this show’s regional significance isn’t entirely without merit; it’s just misguided. If there is a ‘local flavor’ here, it’s not to be found in the art on display, but in the fabric of the show itself.

The fruits of the fellows’ grant year range across media—video, oil painting, photography, and sculpture are all represented—and aesthetic, from the poetic to the cinematic to the downright ugly.

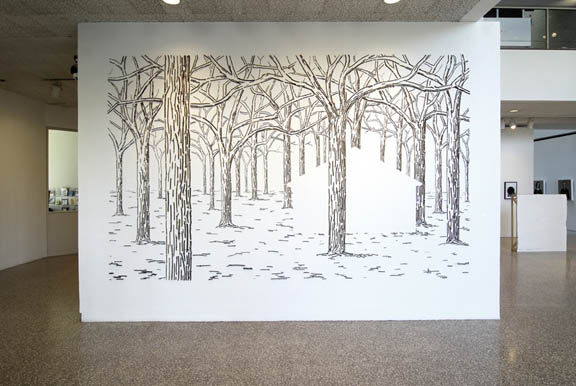

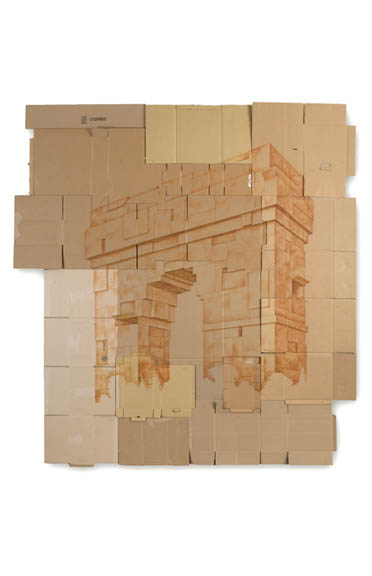

The most immediately impressive works are by David Lefkowitz, whose large-scale architectural renderings remind us that art executed simply is often the most suggestive. Using a variety of building materials such as sheetrock, caulk, and cardboard, Lefkowitz explores the mediations through which we approach the ‘natural’ world.

In all his pieces there are obvious traces of the artist’s mark—a bit of pencil sketching which he has failed to erase, or screws that hold the work together. We see this most evocatively in Outbuilding, an assemblage of amazingly uniform twigs which have been glued to the gallery wall. These twigs are arranged like building blocks to form the shapes of trees, a reconstructed woodland out of which emerges the outline of a little cottage made up of negative white space. A closer examination of these bits of forest refuse reveals a tangle of gossamer-like, translucent strands, excesses of the hot glue that has oozed out from between the wood and the gallery wall. Outbuilding,like the other works, externalizes the constructedness of all artistic representation, in the most literal sense; art as forging, and foraging—trawling the world for its generative capabilities. In Lefkowitz’s hands, art is never a window to the world, disinterested and objective, but always an intervention upon it.

In his collection of altered photographs and sculptural arrangements Aaron Van Dyke demonstrates a similar concern with the image as signifier, although what he makes of this notion could not be more different.

In Van Dyke’s work, images appear and reappear in multiple contexts, rehashed and recontextualized in a frantic attempt to efface the codes within them. Advertisements are reversed or up-ended, and whole blocks of text are repeated only to be rubbed out. With these scratch-marks and white-outs, visual material is simultaneously appropriated and diminished. In two wooden sculptures the photographs hanging on the wall are recycled, then trapped in a bulbous yellow spray foam like bees in honey. These sculptures are filled with clues that go nowhere—moustaches, a photo of the Baader-Meinhof Gang, a building cut by Gordon Matta-Clark. It’s the refusal of a frame of reference, an externalization of being mired in thought, the flotsam and jetsam of an intellectual implosion.

This kind of abject refusal is at its most perplexing in a wooden platform, about three feet square, which lies flush against one gallery wall. Painted black, the platform is fringed on three sides with short strips of shiny black plastic. It lies on its back pitifully, with four stubby, inutile legs poking the air, like an overturned beetle. Its belly has been sliced right down the middle, exposing the yellow spray foam of the other pieces. It is this profound unlikeability that distinguishes Van Dyke’s work. So disgusting, so pathetic!

Still, there’s something missing in this amalgamation of nihilistic junk that makes experiencing it a touch underwhelming. In order to keep the viewer pinioned in this position of unhappy looking, these sculptures and photos could stand to go further. It may be that what’s needed is a negation so present it cannot be ignored, a whorl of meaninglessness so great that there is no escape.

In her videos and photographs Susanne Kosmalski exhibits a fascination with the intersection of three categories of masculinity in the American West: the White cowboy, the American Indian, and the Mexican. In Show/Down, a non-synchronous, two-channel video installation, Kosmalski juxtaposes shoot-‘em-up footage from a multitude of Hollywood Westerns. On opposing screens, cowboys, Indians, and Mexicans alternately do battle across their film frames (the shooters fire on one screen, hitting their targets on the other), while a non-synchronous soundtrack of gunshots and galloping horses provides context. The result is an emphatic presentation of the racialized tropes of masculine violence, without much of an interrogation of such tropes. Unfortunately, while she begins with some interesting source material, Kosmalski does little beyond present it to us. The piece’s momentum is driven by the sheer plethora of so many similar images, not by anything in the piece itself. Her interventions remain at the formal level, so that Show/Down results in little more than a clever conceit.

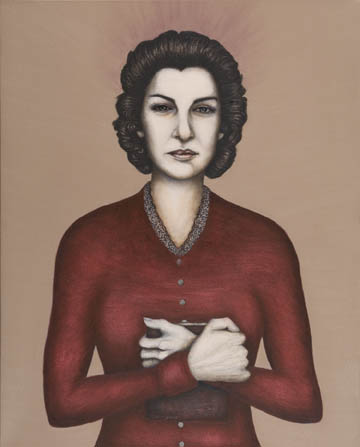

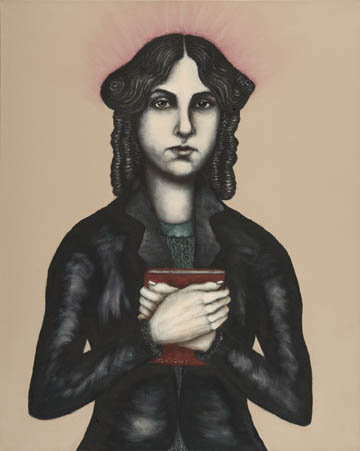

In his oil portraits of women writers Jay Lance Wittenberg also explores the representation of gender in contemporary culture, albeit in a radically different way. Many of these women are so well known they are almost predictable: Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, Louisa May Alcott. Others are more obscure, but all are depicted from the same perspective and pose—frontally, with arms folded primly at the waist, their hands clutching an unmarked book. Faces and hands are subtly rendered, due in part to the woodcuts Wittenberg makes of each of his subject’s faces before he paints them. Meanwhile, the plainness of the surrounding details—their demure dresses, the bland beige backgrounds, everything that is not them—suggests a simplicity that has been forced upon them, as if they’ve been sent away to a nunnery.

In the hands of a male artist, this compulsive depiction of literary ladies becomes wonderfully perverse, perhaps despite Wittenberg’s best intentions to the contrary. In his earnest regard for these women, he doesn’t seem to recognize the hairiness of restoring them their due place, that in retrieving them from scholarly oblivion he cannot help appropriating them. However, there is a fierceness in his subjects that suggests that they know what he does not—that they can’t be inserted into history, but only intrude upon it, as powerful, yet not necessarily benevolent ghosts. They seem to see what has been done with and to their work since it was ‘rescued’, what Wittenberg himself is doing to them. ‘From our cold, dead hands’, those graying, tightly wrapped fingers seem to say.

Since 1981, the McKnight Fellowship (like the Jerome Foundation’s awards for emerging artists) has been a primary factor in combating artistic flight to major art centers. This kind of contribution to the infrastructure has resulted in an arts community sophisticated enough to resist a metropolitan inferiority complex. If this rather cacophonous show says anything about ‘regional sensibility’, it gestures toward the elusive and contradictory character of ‘Minnesota art’—whatever that may be.

The McKnight exhibition closes on August 13.