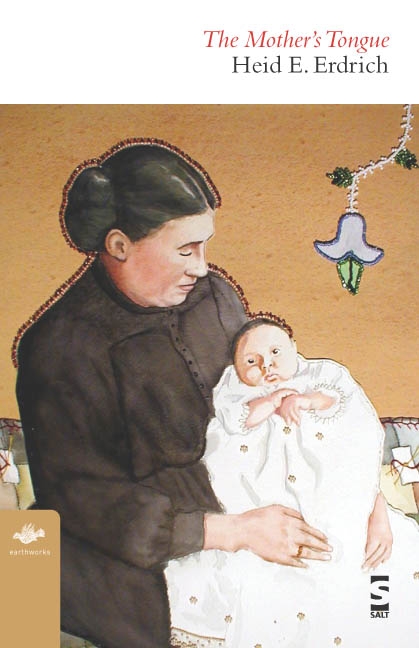

Learning to Talk: “The Mother’s Tongue”

Erin Lynn Marsh reviews Heid Erdrich's book "The Mother's Tongue," a collection of poems on the stages of motherhood and the evolution of language.

What immediately stands out while reading Heid E. Erdrich’s second collection of poems, The Mother’s Tongue (Salt Publishing), is that these poems are written by a master storyteller. Each poem comes with a place at Erdrich’s feet as she poetically passes down her myths and advice. I spoke with Heid Erdrich about writing this book and her creative past; her responses illuminate the creativity of motherhood and the gentle beginnings of language.

The poems in this collection are ordered loosely according to stages of motherhood: the decision whether to have a child, pregnancy, birth, and the return to the world. The collection reads as a sort of handbook for new motherhood, both the difficult and joyous. For instance, in her poem titled “Look” Erdrich writes: “When I say my son’s eyes are like a lake/I mean they reflect that same slate blue/but with depth: rocky bottom, silt bottom”. Here we see the wonder of a new mother for her son, but earlier in the collection Erdrich stresses in her poem “Sisters Stay On the Other Side” the fact that motherhood is indeed a choice not all women must make:

Sisters stay dry on the banks, do not even

touch toe to test the water. Stop your ears

when you hear siren sounds: wet, sweet wails

that insist you can never understand

life, love, woman, man – until you birth

or nurse or raise a child in this world.

Erdrich started the poems in this collection in 1998 after the birth of her son. She found that motherhood made her more creative, distilling everything down to its essence. But, Erdrich says, writing with an infant is “very intense”. She had to keep poems in her head until she could get them down on paper, or poems might wake her up, forcing her to write instead of sleep. Erdrich was able to keep this schedule because of her unique theory, formed in college, in which she uses her brain like a computer. She can ask her brain to run a “background check” on a subject while she sleeps. This process could be the reason many of Erdrich’s poems are grounded in a knowledge rooted in dreams. For instance, in the poem “She Dances”:

But I once dreamed my friend a dress:

one in slipping honey colors of satin

with black bands. Its music came with

its cones jangling and flashing near each

flower-print cloth outfit then on to the next.

These poems speak in a distinctly feminine voice; not only in subject matter, but in cadence as well. In poems like “Changeling”, Erdrich uses voluptuous vowel sounds to fatten the poem: “You grow to gold, your glow/too much honey. I look away, or,/rarely, allow my eye to rest/a moment on your shining, sweet form.” The reader can hear the poem’s shape, can decipher the womanly form. Many of Erdrich’s poems are more straightforwardly feminine, taking on the bodily changes pregnancy induces, as in “What Pregnant Is Like”:

You get bigger.

I mean you enlarge,

diffuse, push boundaries,

cover the whole of woman,

man, and child. You balloon,

stretch in unexpected directions,

Erdrich found that pregnancy is a contemplative time; she thought a lot about the role of women in the proliferation of language. Children first experience and acquire language in utero, hearing the sound and rhythm of the mother’s voice. As the child grows, this voice is authority, storyteller, soother, and advisor. The last poem of the collection, “Motherhood As First Language,” is the culmination of all the myth and advice of the previous poems; Erdrich asserts that motherhood is truly a literary act:

The mother’s tongue points to the truth about those first months

with an infant – nearly impossible to convey. To mother is to teach

language, a great joy and saving realization that makes the tedium

and exhaustion of early motherhood something we survive and

from which we grow.

Later in the poem, Erdrich explores further the idea of one’s mother tongue or native language:

And again, the mother’s tongue is the Ojibwe language that my

mother was discouraged from learning, that her father used in

prayer, that was banned, punished, obliterated by government plan,

and the power of the church, and by the sheer weight of trade

language as survival language.

While reading Heid Erdrich’s book, one is brought into the experience of motherhood through the myriad of voices the author has taken on in her journey. This book is an exploration of our culture’s relationship with the term “mother” and of the beginnings of language.