Noting the Throat/La garganta, anotada

Thinking through speech and power with artist Allison Bolah and writer Zahra Patterson: how the legacy of colonization shapes how mouths form consonants and vowels, and how Diasporic Black artists activate polymorphic uses of language

In 1517, the Spanish missionary Bartolomé de las Casas, taking great pity on the Indians who were languishing in the hellish workpits of Antillean gold mines, suggested to Charles V, king of Spain, a scheme for importing blacks, so that they might languish in the hellish workpits of Antillean gold mines. To this odd philanthropic twist we owe endless events…

Jorge Luis Borges

It is not the Black child’s language that is in question, it is not his language that is despised: It is his experience.

James Baldwin

I’m Venezuelan by birth, though I’m told that as a little kid I had a Mexican accent; they dub children’s television in Mexico City. It was not until I moved to the United States that I consciously trained myself to drop my Ss like other Venezuelans. Because of cognates, my English is closer in tone to Frasier’s. I have a strong accent, and a small speech impediment. I do not sound like many other people.

There’s an absurdity to the essentialization of language: it’s a little frivolous to correct the noises made by the mouth to re-imagine one’s inner rumblings. There’s something even more absurd in the rectification of children’s voices. Even as a child, I was aware of an elusive sadism in the way I was corrected. This kind of culturally-sanctioned chastisement carries a record of communal relationships—parent to child, teacher to child, child to child, etc.

The artist Allison Bolah engages with different, competing notions of community and aesthetics. The video installation No Accident takes us in alphabetical order through the “correct” pronunciations of common words. Like an ironic exercise in an accent and stutter reduction course, the frame does not allow the viewer to focus on anything other than Bolah’s mouth. We are left to observe various oral motions: the rounding of the O’s, the peaks and valleys of the U’s, the sharp kah of “cat,” and so forth. There’s a series of primary word associations, and through them there’s an eccentric poetry, one that underlines the absurdity of the exercise.

Through an examination of the middle-class roots of her accent, Bolah’s No Accident is able to discuss the (very) American circumstances under which Black people’s accents are formed and understood:

“…A ‘neutral’ North American accent is either prized for the doors it might open or reviled for its seeming alliance with whiteness. Indeed, accent as a marker of or challenge to ‘Blackness’ remains a significant dimension of my experience in all of the racialized spaces I encounter. As a child I was admonished for adopting my parents’ Caribbean accents and made to repeat Ts, ‘th’, and other sounds precisely.”1

In North America, being middle-class is understood as a personal achievement2 rather than a socioeconomic position. Because of its perceived virtue it is granted a prestige in democratic rhetoric.3 The original concept of a middle class, however, is designed in the specific image of the European “middle classes” that formed and expanded through the industrial revolution. It stands to reason that the public education systems of these countries (and subsequently that of their empires) formed in conversation with mass mechanization and mass consumption, essentially as managerial schools. This is apparent in the way that classes are structured. The caveat is that both in the United States and the Americas, education was, and still is, widely understood to be the “legitimate” path to the middle class, how that class aesthetic is properly absorbed.

It’s important to highlight ideas of class within the various discourses about language. “In my view—” notes Bolah about No Accident, “communication, and thus any language of art, is bound to community and context; creating and reading a work of art depend on both.”4 She elaborates that “To identify with a particular community is to consciously engage in the politics of one’s relationship to that community.”

Unlike their English counterparts, there is a gap within the (white) North American mainstream discourses on the subject of class and voice. Asides from Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby or Donna Tartt’s The Secret History or The Goldfinch, I have not readily come across popular American literature that explores the role of syntax in American society. This is a particularly (and conveniently) odd neglect if one is to consider how a considerable sum of the white middle class audience is only three generations or four removed from refugees and economic migrants, and that those families often only had access to higher education after the G.I. Bill opened university doors to most white males of the G.I. Generation. In the many different Black artistic and literary discourses, however, the subject of voice appears and reappears. Bolah herself links her work with that of other Black writers and artists like Toni Morrison, Lorna Simpson, Glenn Ligon, and Kwame Anthony Appiah while simultaneously emphasizing her particular position:

“I think of myself as ‘diasporically’ Black and belonging to many communities throughout the African diaspora, particularly those in the Caribbean, North America, South America, and the United Kingdom…By excerpting, excluding, annotating, or otherwise altering them, I ponder the influence of the patterns or narratives of these shared places/spaces on community members’ lived experiences. Indeed, I have come think of my work as comprised of acts of citizenship within my various communities.”5

Diasporic recalculations of race have a particular relevance in the Caribbean, where plantation economies are constantly reinvented.6 It’s misleading for me, an individual, to speak for (or to) 30 million realities. Nonetheless, I think it’s fair to say that we as Venezuelans have a complex relationship to the concept of an African heritage:7 our history is clear, delineated through our cultural output. It appears we would like for it to be less so, and for the Black role to be limited to a distant cultural heritage that we’ve assigned.8 It’s a question of aesthetics: an inherited repudiation of our own Black aesthetics.

With this lens in mind, I admire certain notions of Pan-Africanism. Rather than regale to the distant past, there are non-Africans open to engaging with the continent without making a fetish of said place.9 The American writer Zahra Patterson’s Chronology, one of such engagements, highlights the personal conflicts inherent in an honest exploration of translation.

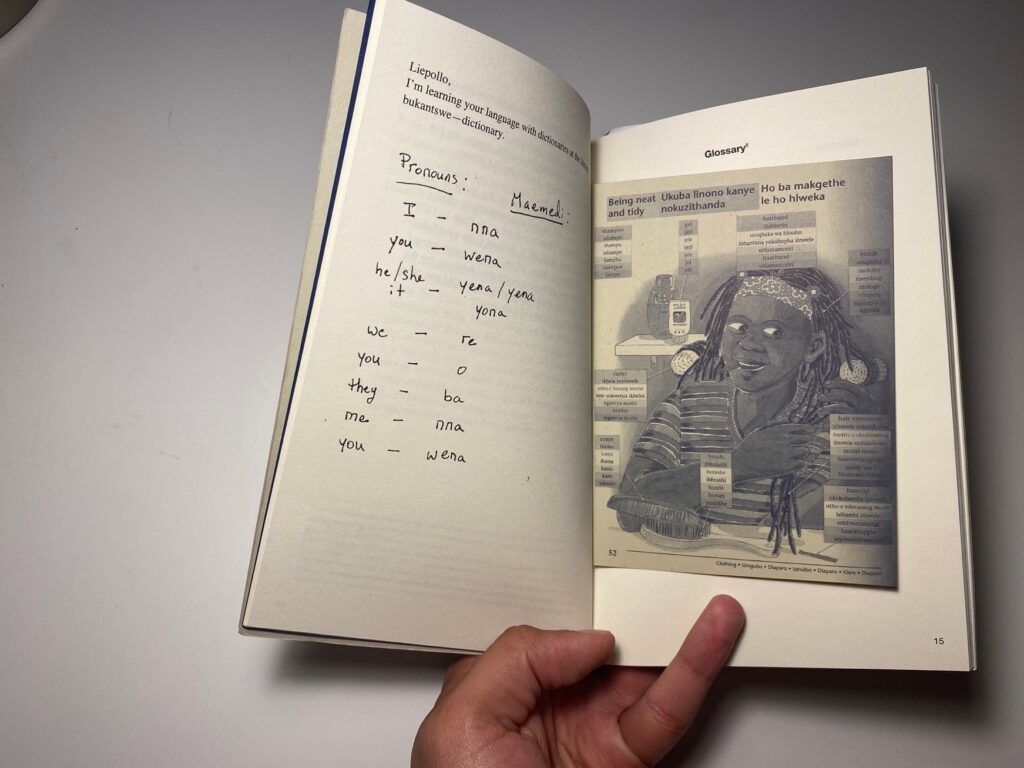

Inspired in part by the Korean American artist Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée, Patterson uses the personal—her friendship with the late Lesothan writer Liepollo Rantekoa—to explore the politics of the written Sesotho language and its translation within the 20th and 21st centuries. It is not simply a critique of orthographic politics because Patterson, through her diaries and personal emails, submits herself to evaluation.

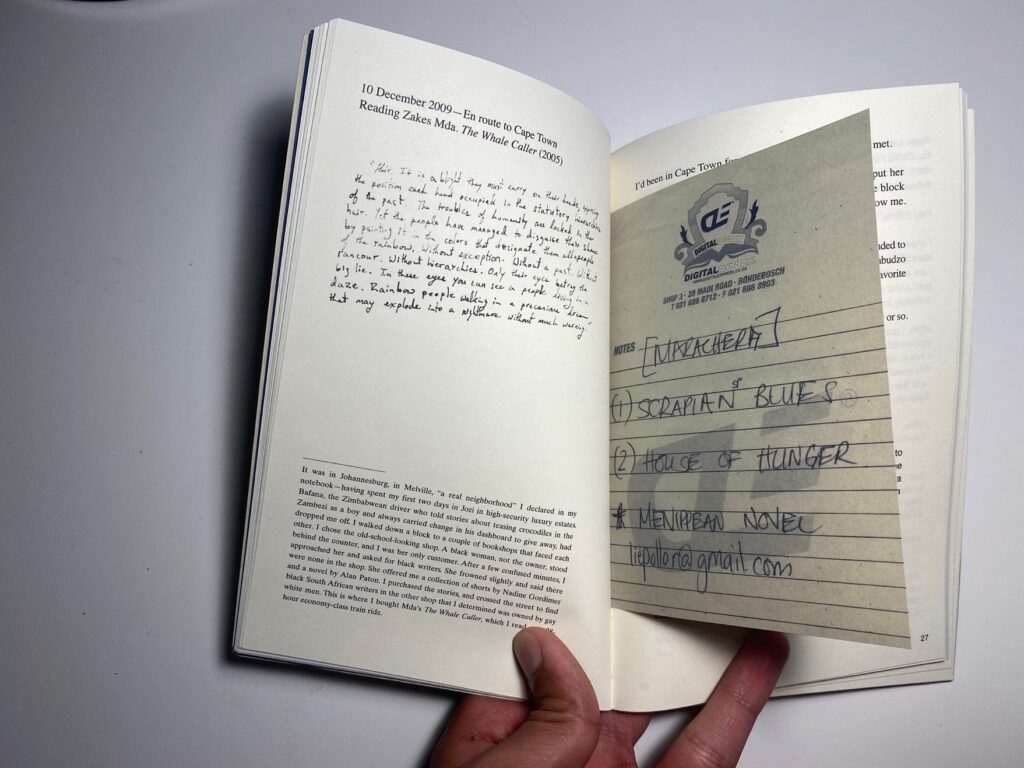

As implied by the title, the book challenges sequential time: it opens with a 2011 email from Rantekoa and travels back, in diary form, through South Africa in the end of the noughties, and then, through library research, back into the early 20th century, to return to 2013 and beyond into the late 2010s. The fragmented narrative resembles some of the ideas behind paintings of American artist Julie Mehretu, in that in Patterson’s writing, like Mehretu, there is not an immediately apparent focal point from where one can comfortably relate back.10 The “correct”-ness we crave is absent.

Sample of Chronology. Photo courtesy the author.

Sample of Chronology. Photo courtesy the author.

The prefix in postcolonial implies a teleology, a “leaving behind” through a movement of time and thought. This subtle implication that through the postcolonial lens we can somehow move beyond the legacy of the colony is one of the many ways in which we, as thinkers, explicate ourselves from the dynamics that shaped our world.

Can we leave the colony? Maybe. maybe not.

At the root of their conceit, American countries are colonial, and we as individuals and ethnic communities react in relation to that legacy. Who looks at a map and thinks otherwise? We tend to react with an idealism that might not be at all useful in retiring these structures: we carry so much of them; like the bacteria before us, we live in colonies. For us writers, the streams with which we traditionally come to knowledge seem to always have a muddy European tint. This, as Patterson points out, is reminiscent of the way that European linguists indexed South African languages in the early 20th century:

“One of the first reactions of the European explorers and colonists, on being confrontedb y a world that was wholly novel and outside the bounds of their experience, was to reorder it according to their existing structure ofk nowledge. This entailedi mposingt heir intellectualg rid on the unfamiliar masso f detailt hat surroundedt hem. Linguistic and otherb ordersa nd boundariesw ere erectedi n ordert o restructuret he Africanw orld in a way thatw ould make it more comprehensiblet o Europeans. Once linguistic expertsh ad anchoredl anguagess patially b y erecting b ordersa round regulationso f their grammar and vocabulary, t hey sought to stabilizet hem over time by tracing their historical roots.”11

If in their logic our counterarguments reflect their European origin, with absolutist claims to universality, are we unconsciously replicating that claim? Postcolonial theory has many addendums, and they conveniently get lost in translation through the undergraduate version that our most fashionable writers expound. In the game of justifying ourselves, we reproduce enough of the colony to keep on seeding the doubt: is the way that I speak, in fact, real?

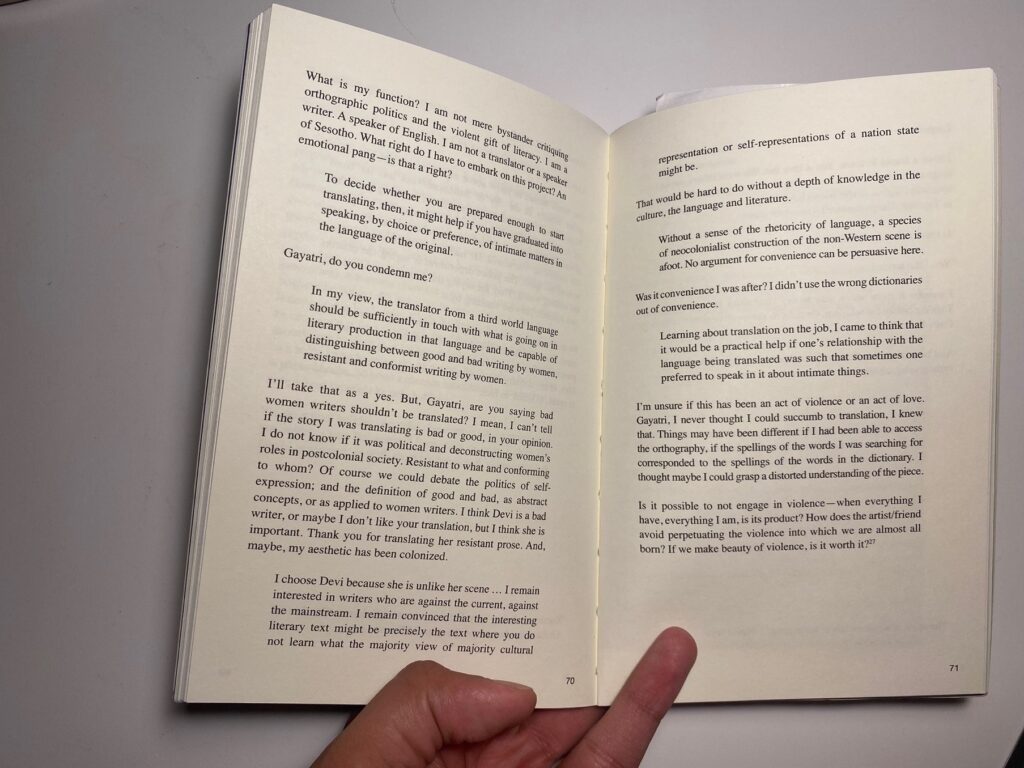

A more useful action—Bolah and Patterson’s—for when we find ourselves in this state of being is to interrogate: what is my function? How are my values being reflected in what I’m reading? Like Saint Augustine before her, the most resonant moments in Patterson’s Chronology are not in theology but confessions. Towards the end of the book she has a “conversation” with theorist Gayatri Spivak. Patterson, in a state of doubt about her relationship to Sesotho, a language she does not fluently speak,12 asks questions to the paragon: “Gayatri, do you condemn me?” Spivak responds through quotes: what resonates to Patterson in the pages of “The Politics of Translation.” Suffice it to say that Patterson-Spivak castigates.13

In the early 2010s, and perhaps unaware, Bolah and Patterson collected and synthesized voice: its modifications, and their relation to a Diasporic Black identity. In a challenge to notions that appear concrete, they both speak to a specific concern about the role of individuals in the (polymorphic) presentation of language: the ideas behind how our throats are categorized in our public and private histories.

In short, please stop lecturing me about run-on sentences. I am aware.