A Generic Dance Essay

Following the conventional forms of dance writing—in order to flout genre, expose the solipsism of white cultural memory, and track the marking and unmarking of bodyminds in the marketplace

To begin an essay about dance and performance, even the imagined performance in this essay, there should be an intriguing introduction, an opening line that draws readers in. It’s a good writerly move to include a striking image or a poignant moment from the performance. Perhaps something like:

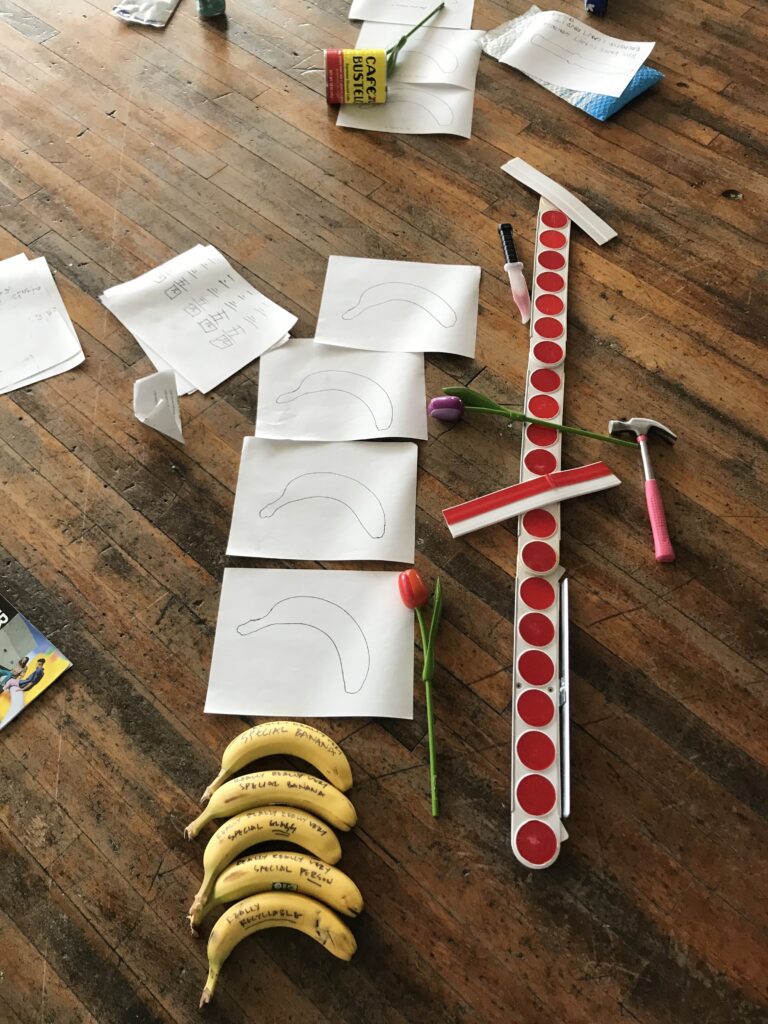

The curtain draws back, or does the fourth wall break? A person stands center stage, holding a banana in front of their eyes like a pair of glasses.

Have I gained your attention? I’m building anticipation for what happens next—context is key.

This is an essay written by a white, cisgender, non-disabled, thirty-something dance artist and scholar that explores the concept of the generic.1 In writing a “generic” essay about dance and performance, I travel through formal cliches and down rabbit holes of cultural references, juxtaposing thoughts on writing about dance and performance, the violent solipsism of white cultural memory, and contemporary art’s imbrication in capitalist enterprise. To make sense of things, I follow form but flout genre. In other words, generic is as generic does, which sometimes is to point toward the specific.2 (I should point out that an introductory section such as this should include some useful “signposting” but should avoid being overly didactic.)

Next, the author should speak directly to the reader: provide information that refines, makes exact, makes concrete. One might include a date, a time, a place, names of people who enact and produce the performance. Generically, an essay about dance and performance should include a purpose and thesis and critical angle from which to explore the artists’ work. Perhaps a quote from a respected performance or dance scholar goes in this section; it’s important to engage the extant discourse, to build credibility.

In the words of genre-crossing, white pop star and businesswoman Gwen Stefani:“Go Bananas! B-A-N-A-N-A-S!”

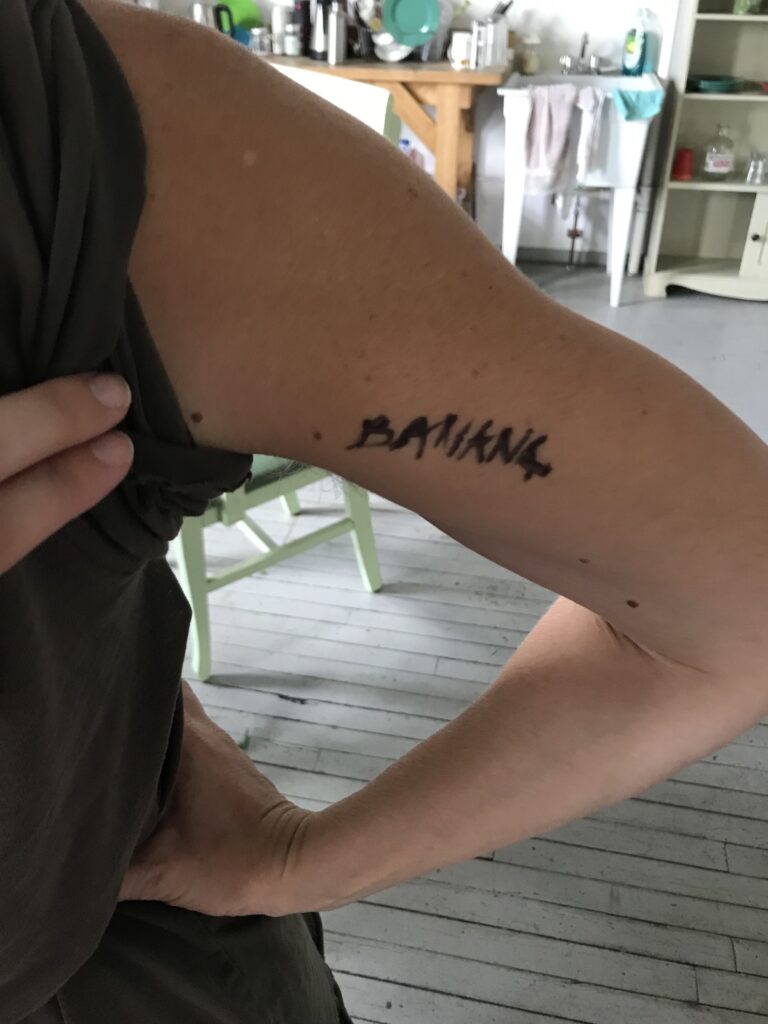

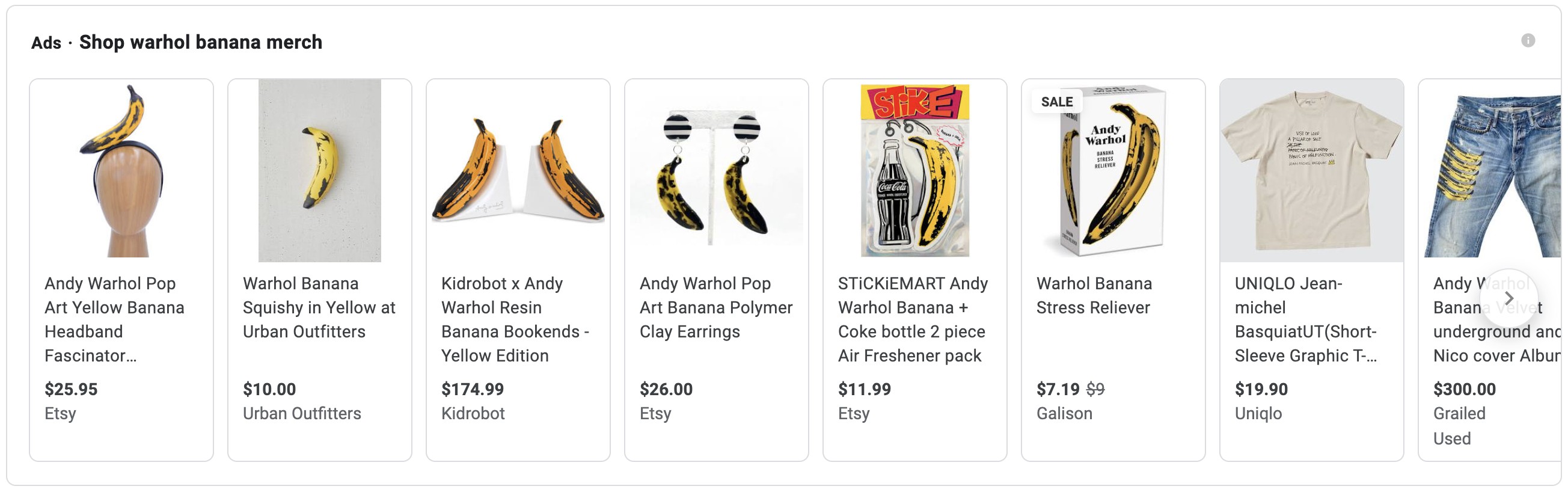

No doubt, it matters who an artist says they are, how they identify, and what they say they’re doing and for whom. The essay should probably include a line or two drawn from the artist’s press release because, of course, what the artist says about their work is part of the work itself. Branding is the performative act of establishing a salable persona for a product. One definition of “generic” indicates the lack of a brand name. Did you know that professional artists of all identities and disciplines spend much of their time promoting their work? Cross-promotion is the best promotion. Creativity is as creativity does under capitalism.

Did you know that words can dominate, define, and mistranslate dance and performance? Writing can objectify bodies, yet our bodyminds are woven through with words. I can’t remember who said, “There is no body without discourse,” but I’m quietly confident that someone wrote it while discussing dance and performance. Indeed, memory is like performance: both ephemeral and reiterative. Except performance isn’t ephemeral (see the Peggy Phelan vs. Phillip Auslander debate of 1990s.)3 If it was, it wouldn’t be marketable. Here would be a good place to interject a thoughtful question for readers to ponder: If you don’t capture performance in another medium, does it disappear?

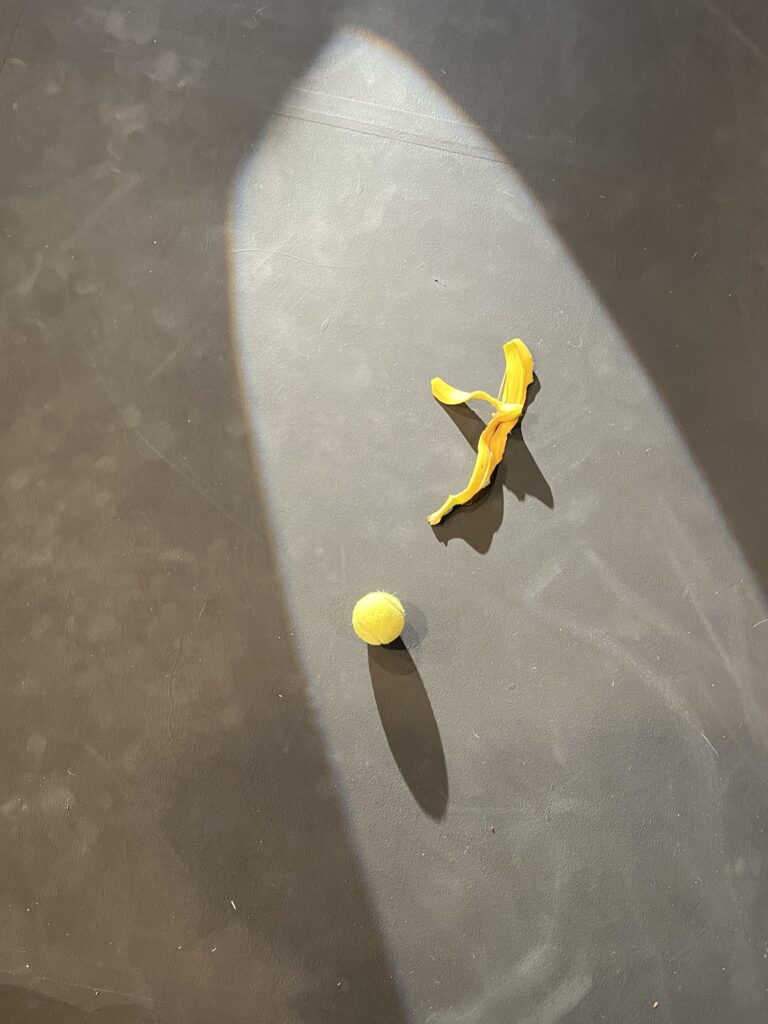

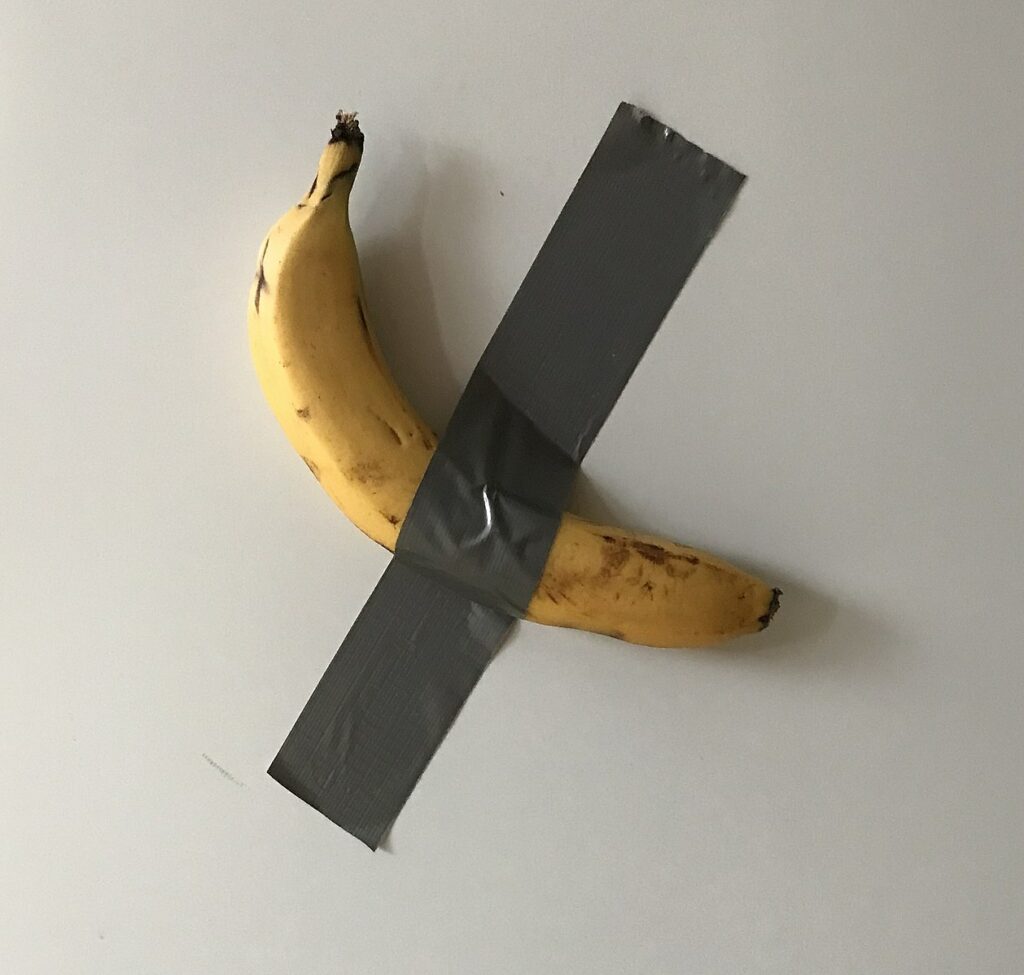

What is disappeared when we presume sameness? I want to be crystal clear here: Dcnae ins’t a uvnierasl lganague. It is not a small world, after all, despite what Walt Disney wants to sell us. Dancing, like writing, quickly slides into specificity. Movements, like words, like objects, mean different things depending on the context. For example: A banana is a food, is a comedic phone, is a peel on which to slip, is a phallus. It is a commodity on the wall. A body is sensate, is an object, is a tool with which to write, is the way we come to know what we know, is our bread and butter. It is a commodity on the stage and screen. Expectations are rife.

Dance, monkey, dance!

So many signifiers to explore, yet my imagination is girded by cultural scripts. There’s a slippery slope between the “generic” and essentialist, universalist perspectives. Despite this essay’s attempt at a generic approach to form and content, my personal associations inevitably affect the movement description that comes next. Perhaps the best approach is to try to unlearn what you’ve been told, to work to unfold the shape your perspectives have been molded into. For example: Bananas aren’t always yellow. Did you know that there are hundreds of varietals of bananas? Did you know that Cavendish bananas have essentially cornered the global market?4 Did you know that Portuguese-Brazilian-turned-Hollywood performer Carmen Miranda inspired the Chiquita Banana brand logo? Do you know what she had to navigate throughout her career in the mid-twentieth century? Did you know that the United Fruit Company exploited working people and newly democratic nations in Central and South America throughout the past three centuries? In 1950, the Chilean poet-politician Pablo Neruda wrote of corporate imperialism, bananas, and bodies:

When the trumpet blared everything on earth was prepared and Jehovah distributed the world to Coca-Cola Inc., Anaconda, Ford Motors and other entities: United Fruit Inc. reserved for itself the juiciest piece, the central seaboard of my land, America’s sweet waist. It rebaptized its lands the “Banana Republics,” and upon the slumbering corpses, upon the restless heroes who conquer renown, freedom and flags, it established the comic opera.6

How do we know that we all taste the same flavor when we eat bananas?

In language, which is etymologically related to “tongue,” I capture what I experience, which is not what the performer experiences as they pull back the banana’s peel, which is not the same thing the consumer experiences. Peel slowly and see. After I witness the dancing, I feed you action verbs, vivid adjectives, and poetic adverbs. Hips shake, lips curl, hands caress. The performer winks and weeps and wiggles. The banana is pale yellow, smooth-skinned, and curved. One sold for $120,000 at Art Basel. Language replicates, recreates, regenerates, reimagines (never not-written-upon) bodies moving through time and space and access to capital. In 1994, a biopic called Bananas is My Business told Carmen Miranda’s story. I haven’t seen it yet since I can’t find it anywhere, online or offline, to rent or buy or watch for free.5 Does anyone know how it ends?

Generically, an ending demands recapitulation, or perhaps the posing of a probing question that invites readers to continue to reflect. Here, I offer an uncomfortable ellipsis for people who think their bodyminds are unmarked or are not part of the marketplace: tongue in cheek, hand in wallet, legs straddling the footlights. After the curtain call and the applause, a bunch of thoughts.

Andy Warhol, eat your heart out.