Circular Healing

Rosy Simas (Seneca) on non-transactional art practices, creating spaces of rest and respite, and the overlapping of past, present, and future

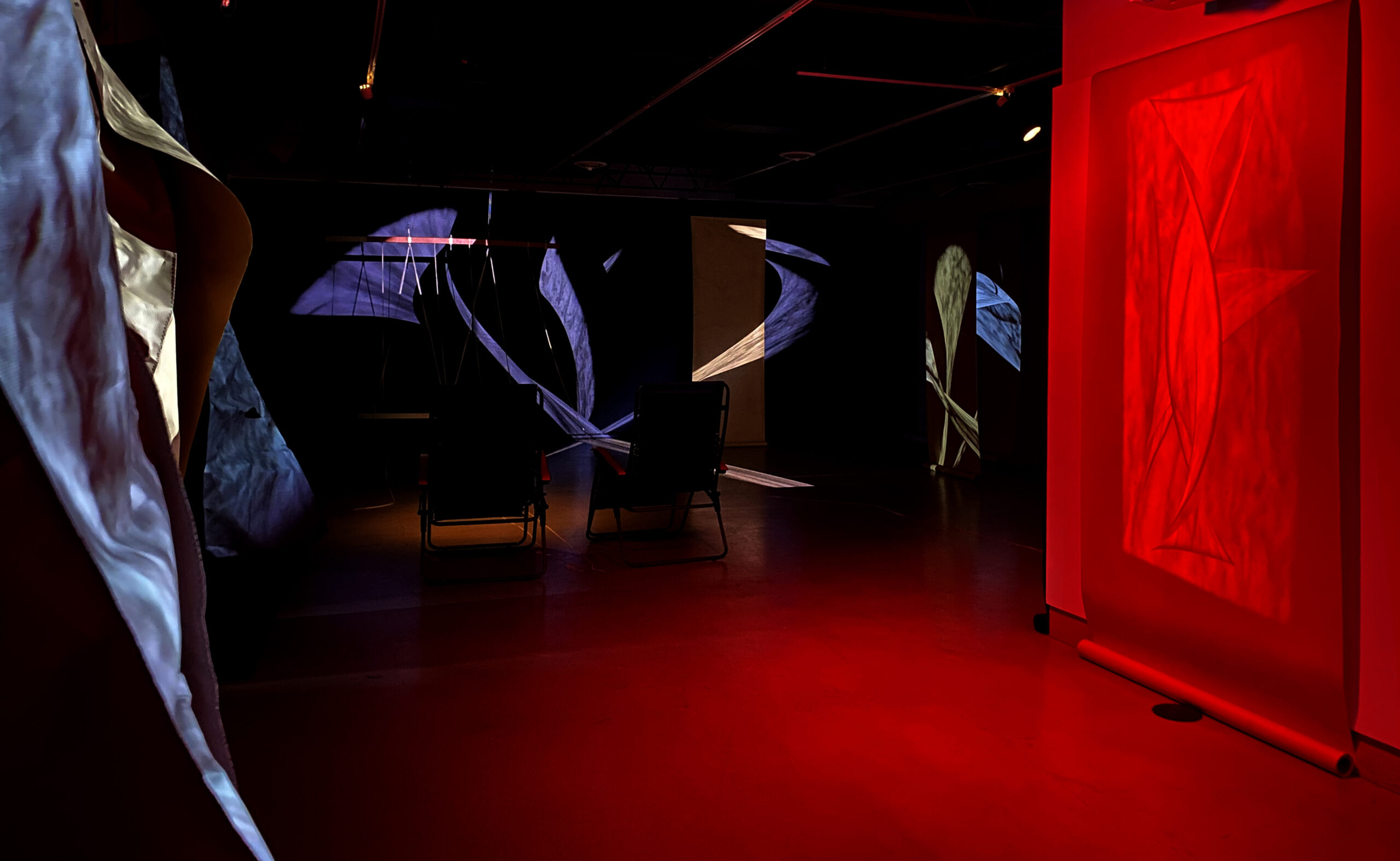

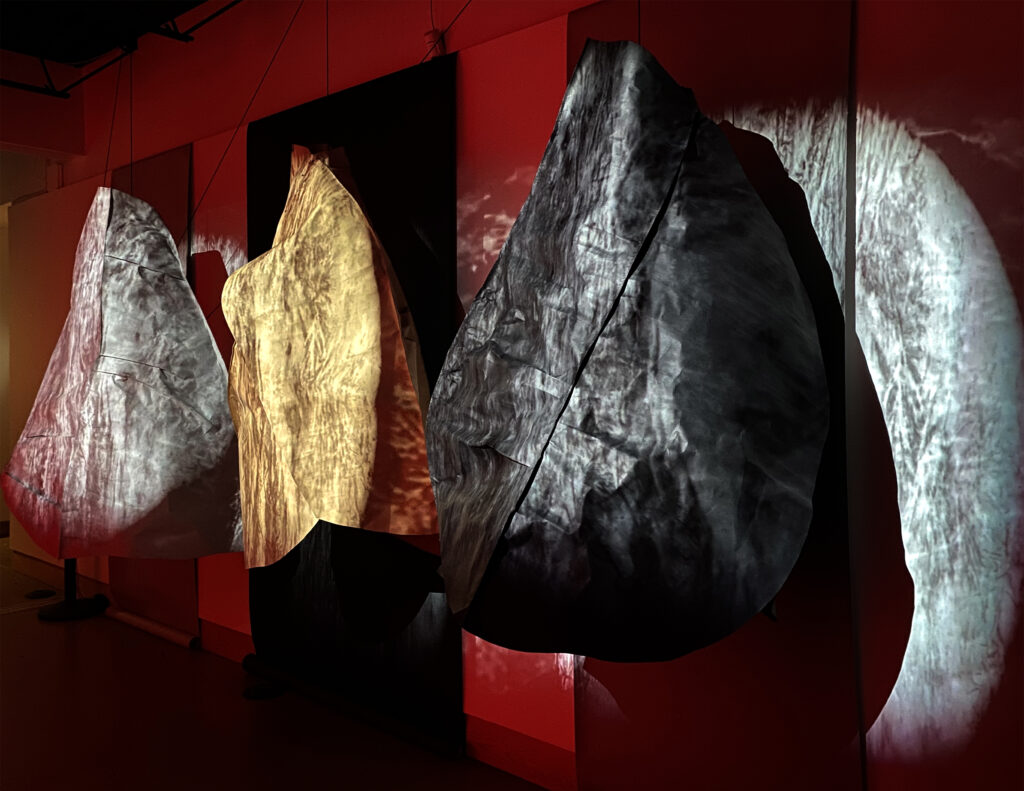

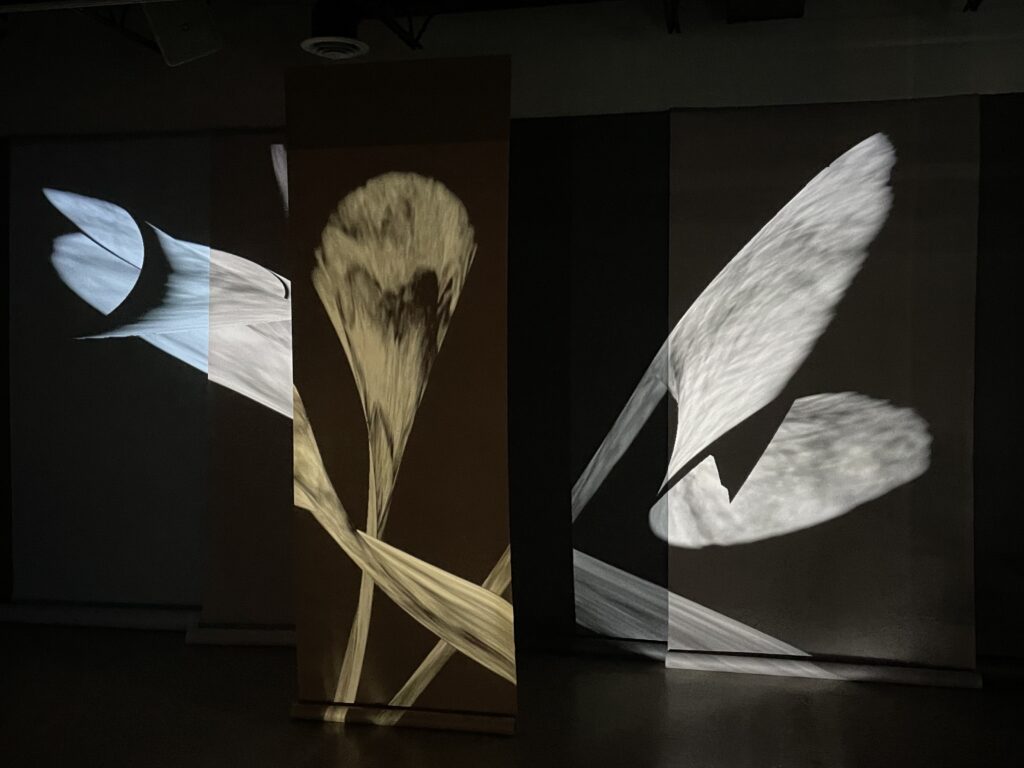

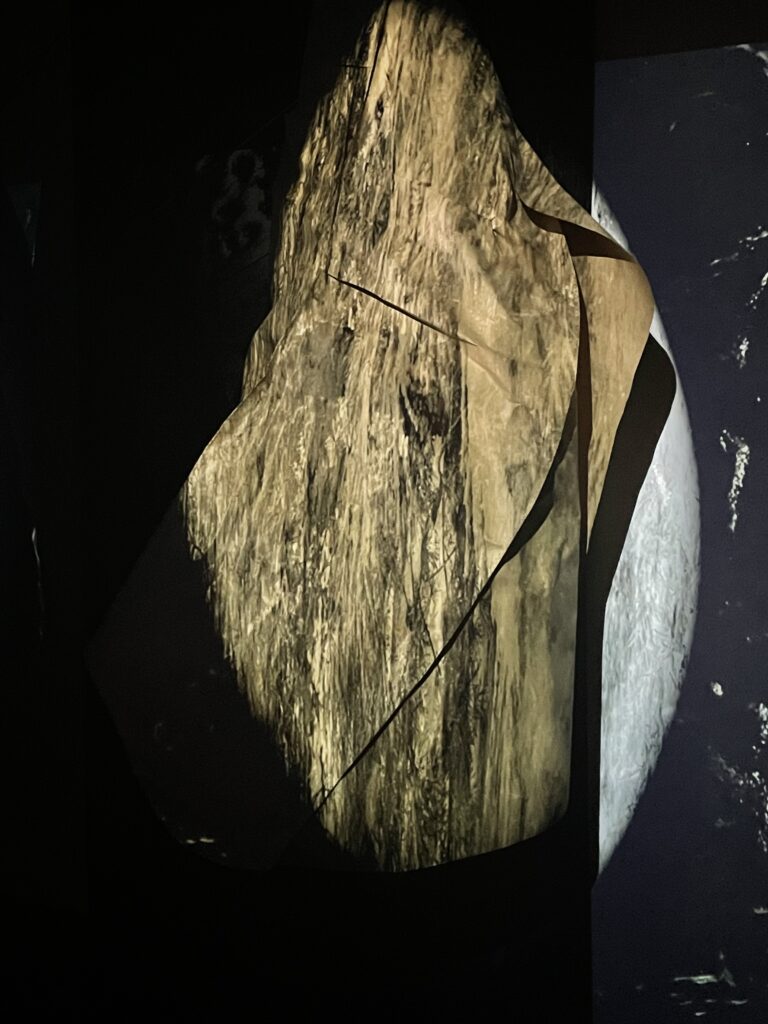

introductionRosy Simas (Seneca) is a transdisciplinary and dance artist who has historically presented her work as a choreographer. Simas’ projects merge movement with media, sound, and objects for stage and installation. She unites cultural concepts and images with scientific and philosophical theories to create work that is literal, abstract, and metaphoric. Her work weaves themes of personal and collective identity with family, sovereignty, equality, and healing. Her latest installation, yödoishëndahgwa’geh (a place for rest) is an inter-sensorial space of moving image and sound by Simas and her collaborator, composer François Richomme, with the intention of creating an ephemeral environment for rest and refuge. I sat down with Simas and her partner, performer Sam Mitchell, in the gallery of All My Relations Arts to chat about non-transactional art practices, creating spaces designed for healing, and the circular components of her work.

Juleana EnrightFor yodoishendahgwah’geh (a place for rest), you worked with composer François Richomme, whom you collaborated with before. What was the vision for and intention behind the soundscapes visitors are engulfed in?

Rosy SimasMuch of the sound is pieces that were created previously. The process that François and I use to generate movement to dance, film, and sound is that I come up with the concept for the overarching project. We do field recordings of people or sound or places. Then we start working with performers, rehearsing particular improvisation dance scores, and he refines the sound over the time that we’re developing the dance. He composes the music for the movement that’s being created. It’s called generative sounds, a computer program that actually generates the sound in a particular way. Then I take film recordings and edit to his sound. So we have this sort of cyclical process where his work is informed by the movement that’s being made for the dance, and then I’m utilizing that sound to make movement through film. This piece is really a transitional piece. Between the first work we did together and the second work, we also had a transitional piece, called Transfuse. Now we’re in between again, and this transitions into whatever the next work might be.

It’s a way for us to fulfill the visions that we had, or ideas that we had for the last piece that didn’t happen, and also recycle and reuse something in a new way. It’s always different. This whole iteration here, it may be the same film and it may be the same sound, but it’s put together and image-mapped in a completely different way so that it becomes a whole new installation.

Because the concept was around a place of refuge, of resting, of having space to grieve and condole and feel, I chose compositions of his that would not be overwhelming in a sensorial way. He has compositions that are roaring water that crescendos and escalates and vibrates the whole space and make you feel like you’re vibrating with the space. Those really impact the body of the audience.

This is intended to not to activate the nervous system, in a way that a movie does. If you go to a movie, there’s a lot of action, there’s a lot of intensity. The idea was to really try to get rid of some of the intensity that we normally have in a performance and take the quieter, more spacious compositions so that it doesn’t overstimulate.

Sam MitchellThere’s something about movie soundtracks that can be very manipulative, emotionally. Working with Rosy’s process for a number of years, I feel very, very aware of when that happens. To be in relationship with something that doesn’t tell you how you’re supposed to feel, that allows you to be just there with it, is a different experience.

JEFrom my experience being at the gallery, I’ve noticed many visitors really taking the time to sit with the installation, exploring it as a temporal and grounding environment, often for periods of half hours and longer. In going along with that concept of offering a place of resting, what do you hope visitors take away the most from the space? What do you hope they contribute to the space?

RSThe primary thing that I hope that people take away is actually bringing attention to themselves. Recognizing that it’s useful to be bringing more attention to their body, to resting, to just being. I know, it’s been a very difficult last year—going on two years—people are dealing with a whole array of things. From COVID-19 to rampant systemic racism, I just wanted to create a space where people could escape that for a little bit, and maybe let themselves just be and rest.

The point of the deerskin lace that’s in the work is to have people touch it and hold it, and, in a way, share their own feelings, ideas, emotions around grieving and condoling, or just having something in their hand while they’re resting. Bringing that kind of presence into the space, there’s always a residue. And I mean in a positive way, what people who are visiting leave behind. I hope that it is generative, in the sense of what they’re leaving behind for other people —what they’re leaving behind within the actual material itself—is a real thoughtfulness. Even if it’s angst, or whatever, but just the presence and the thoughtfulness to have been in the space.

JEIn other iterations of this installation, you’ve incorporated dance and movement from your partner Sam, who is featured on the banner outside the gallery. Though that wasn’t a part of this installation, how is movement still at the core of this piece?

RSI’m really very focused on the experience of the visitor to the space, and them really being able to rest and not creating too much stimulation. So we haven’t presented it with movement or performance or even a durational thing yet, but we are creating film with it—for people to witness who are not in the space—of Sam moving, and there’ll be other performers who will come in.

Rosy Simas, yödoishëndahgwa’geh (a place for rest), 2021. Image courtesy All My Relations Arts.

Rosy Simas, yödoishëndahgwa’geh (a place for rest), 2021. Image courtesy All My Relations Arts.

Rosy Simas, yödoishëndahgwa’geh (a place for rest), 2021. Image courtesy All My Relations Arts.

SMGoing back to what you (Rosy) were saying before about the process being very methodical, slowly revisiting things and constantly having a circular approach, what comes up for me is thinking about how there are a lot of embodied memories within these soundscapes. There are times where I remember certain rehearsals that we had. We’ve also done residency here in Minneapolis and Florida and Oakland; we’ve traveled quite a bit with this work and it’s kind of this slow gathering. What’s been great is to come in here and listen to it. It brings me into the ripple of all that. There’s a kind of a deep involvement with my physical being, with self. It’s not just something that’s outside of me. Now I feel like it has circulated through my body. And that’s really very special. It helps me as an artist grow because then I think about how I can continue to be in a deeper relationship with things. There’s a tradition in Western dance of having the composer create something that is very exterior and somehow we form our bodies around that. For this, it feels like I’ve been breathing this sound. I’ve been living it; it’s in my cells now.

JEThat reminds me of a quote by Yankunytjatjara poet Ali Cobby Eckermann:

Let’s dig up soil and excavate the past breathe life into the bodies of our ancestors when movement stirs their bones boomerangs will rattle in unison.

I was thinking about that in terms of past works, like We Wait in the Darkness, where much of the focus is on healing the DNA encoding and stored body memory of trauma passed down from our ancestors. How do these pockets of work engage the past while preserving the future?

RSSpecifically with We Wait in the Darkness, the initial movements and sound for that came from letters that had been written by my grandmother to my mother. I didn’t set out with the intention of being able to connect with family that has passed on, but that is sort of what happened by engaging with the materials. I guess you could call those past materials.

The future/past thing is a little challenging for me because I really do see things in a cyclical way. I remember once I was sitting with a friend eating lunch outside at Oscar Wilde and there were a lot of older people walking by. I was just very struck by all of the older women and that person sort of laughed at me. And I said, “What if we just think backwards? Like what if, actually, they are the future?”

Why do we always look in this very linear way in the way that we see things, and how we judge age? We all know, as we get older, that we still very often have the same feelings that we had when we were children. I really do believe that those who have passed on are in a different dimension than we are that is not restricted by what we are restricted by. They travel as energy and beings more freely through time and space than we do. And we’re the ones who are more restricted. The things we do impact them and the things that they do impact us. Even using a word like “them” is kind of a strange term to use.

We also carry these genetic scars, or memories within our structure of our body and in how the structure of our body formed. If we can heal that within ourselves, then isn’t that also healing within them? For me, there’s this focus on healing our inherited historical trauma—especially around boarding schools, residential schools, genocide—all of these things that have happened. A lot of people individually I don’t think have a lot of desire to heal themselves. If you think about it as that healing or that repair work is actually repairing what happened in the past—that they’re also receiving—there’s a mending that’s happening. For me, it makes it more critical, more important to focus on, because it’s not just about me. There is a real dichotomy in the sense of New Age thought, predominantly informed by Europeans, white ideas about the body, health and individualism—and then coming from a more community-centered culture and upbringing, talking about individual healing paths is just harder to focus on.

If I conceptually think that the work is about impacting the past and the future—and myself in the present—then the work is easier for me because it has a broader reach than my own individualism, my own individual self.

JEI’ve been thinking a lot about the process of indigenizing our relationship with time and the interconnectedness of now. That it’s always now. Past, present, and future don’t actually exist in these little dimensions we put them in, but, like you said, “circular.”

SMThat’s exactly what I was going to speak about. Probably about a year before I actually met Rosy, we started talking to each other and we had a lot of parallels with our work. One of the things that I started really considering was could I be in relationship to this land, to Kumeyaay land—this was when I was in San Diego—both past, present, and future in simultaneous mode.

I’m also thinking about this relationship to time and the future. It’s probably just because I finished teaching a class on Native film, but the scene in Smoke Signals when Lucy and Velma are driving backwards—it’s a matter of opinion, but maybe they’re driving into the future, maybe that’s their way of indigenizing. They’re going into the future, into the unknown, but they’re going backwards. To just turn things upside down, I think that’s our challenge all the time. In pushing against the sort of cult of the individual, the cult of extraction, to be able to be and find some way of surprising ourselves in a daily, free organization and rethinking. I find that this work does that for me, too.

Rosy Simas, yödoishëndahgwa’geh (a place for rest), 2021. Image courtesy All My Relations Arts.

Rosy Simas, yödoishëndahgwa’geh (a place for rest), 2021. Image courtesy All My Relations Arts.

Performer Sam Aros Mitchell in yödoishëndahgwa’geh (a place for rest). Photo: Rosy Simas.

JEIn your recent lecture series with the Gibney, you spoke about the concept of relationality and how that guides your community engagement and creative process. Can you expand on that?

RSYeah, it’s a bit of an idealism, you know, relationality, because of course we can’t completely escape the capitalist and patriarchal structure that we are predominantly in. I think about it in terms of transactions, the transactional nature of things—a lot around artist equity, and moving away from working in that model. One of the ways that we’re working on the next piece with the performers is that I’m really starting from a concept with the performers that the work has already been created. It’s not about ambitiously moving forward to create a new dance work, but it’s actually about trying to see what is already present. How can what I’m creating around it—which is the environment of sound and moving image, light and set— support what’s already been created? It’s a very challenging, different approach to making a work, which normally for me would be, “What do I want this choreographic work to say? What do I want the people in it to be doing? What do I want them to look like exactly? How do I want them to interact with the film or the set?” Highly directing them in a performative staged work. But starting with this approach, and realizing also that I will fail many times within the creation of the work, that I will get in the way of myself, my ambition—for me, that’s working more in relationality with what is already there.

For the next work, we will be here at All My Relations and the Weisman and much of it will be free for visitors. It’s not that I’m against people paying for things, but it’s a very different experience than performing for people who are paying $30 to see a show. Where there’s a transactional nature comes an expectation that they receive something very particular. It isn’t that they won’t receive something that isn’t of equal value that they’re not paying for—my artistic quality isn’t going to change. What I’m getting at is, how does eliminating that transactional nature shift that relationship?

I enjoyed doing the Gibney lecture and I do enjoy working with them, but one of the things that I didn’t pay attention to was that they were charging $10-15 for people to participate in the lecture. I wouldn’t imagine that any of my Native colleagues in New York would pay that to listen to me lecture, not that somehow I’m not worth that, but that I don’t see myself in relationship to them in that way. I actually wouldn’t want them to pay. I would be honored if they came to the lecture, listened, and asked questions. Of course, I want to be paid by the venue and they raise money to do that, but that audiences pay money for my words— especially because I’m talking about things that are related to my work that are even of a cultural nature—feels wrong. It’s not that I don’t feel that I should be paid to do and to present my work; I do. But I don’t feel like my community in New York City—the Native community, people I have a relationship with, and new people that I will be in relationship with—should have to pay. That’s not how I want to start my relationship with them. That was my mistake, because I didn’t see the ticket price. But I learned a lot from it going forward. That’s what I meant at the very beginning; I make a lot of mistakes. This is how I think about relationality and community engagement.

Rosy Simas. Photo: Imranda Ward.

Rosy Simas, Transfuse, 2018. Courtesy Walker Art Center. Photo: Carina Lofgren.

Rosy Simas. Photo: Imranda Ward.

JEIn regards to white-run institutions or white cube spaces beginning to investigate their relationship to colonial structure, or structure of power—through creating project Three Thirty One, there’s a response to changing the leadership or changing the mentality of what can be possible in a community space for healing designed for Native and BIPOC artists. What has your experience been with creating this residency program? How is it structured and why now?

RSWell, the “why now” is easy: because it was needed. Number one, we were making most of our income from touring work and gigs. That disappeared and who knew what was going to happen? What was left was this really huge hole for Native and BIPOC artists to be able to create in a safe space. At that moment, safe space meant clean space, a space where they didn’t need to interact with a lot of people while they still could create, and didn’t need to worry about getting COVID from somebody else. Being able to offer that to artists and then also creating residencies that are two weeks, 24/7. They don’t live there but they can work any time of the day that they want to and the space is just theirs. There are a lot of artists who make very intimate and private work out of their individual practices, or group practices that require a real kind of privacy around the space that they work in. That doesn’t exist in a lot of places.

The non-transactional aspect of it was supporting them financially, supporting them technically, supporting with space, not requiring that they give us anything in return that we can then use to market them or market our program, telling funders there isn’t any product coming out of this. If there is a product, that’s up to them, but we don’t ask them to make or even have an agenda about what it is that they’re going to do. We’re not going to have them report on it. So I’m trying to just tell funders we’re not a transactional model space. You cannot actually pay to use our space, you can’t rent it. There’s no way to buy it. The space is really for Native and BIPOC artists to use. Trying to actually just teach funders that we don’t have to run on a for-profit model, where you need to see us generating earned income from our actual space. It’s kind of idealistic, but I’m a little idealistic about trying to figure out this transactional piece.

SMOne thing that occurs to me while walking around those studios and that space, the North King Building, is to see how inherently taken up by white privilege those spaces are. I am aware of that in theater and dance, but not so much in art. It’s sort of been this blind spot. I’ve always loved art, always appreciated all the great white painters and have had somewhat of a sort of reverence towards those painters, and it never really occurred to me how problematic that was. So, even as a brown-bodied person walking through those spaces—and the looks that I get—has raised my awareness of how truly revolutionary this kind of stuff is. Totally embedding oneself in the middle of a place like this, and how it disrupts that narrative, is really important. But it’s not enough to just be in there and be like, “Hey, look, there’s some people of color, some Indigenous folks,” but to actually think about the ways in which those spaces are run, conducted, and tended to. I think it’s important to take all that into consideration. I think it’s one of the last frontiers. We’ve looked at literature and theater, and at dance and music, but for some reason art is still staying in that safe corner where that reverence for whiteness is very rarely challenged. I think it’s time for one, to step aside, or two, to share the space. I don’t think they’re going to share the space, so maybe it’s time for them to step aside.

yodoishendahgwah’geh (a place for rest) is on view at All My Relations Arts with a closing reception on September 21st, 2021.

The writer of this piece is currently on staff at All My Relations Arts, but the interview was planned before the venue for the project was chosen.

This interview has been edited for brevity.