Uso Justo: The Fairest Use of All

Michael Fallon describes Coleman Millers award-winning film Uso Justo, in the Minnesota Mavericks program at the Mpls-St. Paul International Film Festival on Wednesday, April 13, at 7:15 pm at the Bell Auditorium. You will like it, he promises.

If you’ve ever faced down an artistic existential crisis, wondering how you’re going to pay your next month’s rent and still find enough creative juice to ply your craft, struggling with what you perceive to be society’s ambivalence about what you do even as you are compelled to answer your Muse’s call—then you should see local filmmaker Coleman Miller’s new award-winning short film, Minneapolis-St. Paul International Film Festival. Trust me, this little (22-minute) B&W work of art will be a balm for your poor artistic soul—for not only does it feature a poignantly bittersweet story about an artist’s rather desperate struggle to make an experimental film in face of all manner of antipathy, but the very fact that the film got made and released at all is a hopeful lesson to any and all artists who strain to get their work to the public.

A quick description: In Uso Justo, Miller makes use of an obscure Mexican hospital drama, reworking it with fake subtitles and special effects and reordering the scenes to create a completely new metafictional film that is unrelated to the original story. In this, Miller merges the strategies of experimental filmmakers of the Creative Commons ilk, who use preexisting materials to produce (mostly) abstract visual film montages, with a storytelling gimmick most famously seen in Woody Allen’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, in which the film auteur dubbed over a Japanese spy movie to create an entirely different story. As a sidenote, many of you will recall the recent discussion on the mnartists.org Forums about intellectual property and usage rights; Miller’s film is a perfect example of the potentials of this growing form of art.

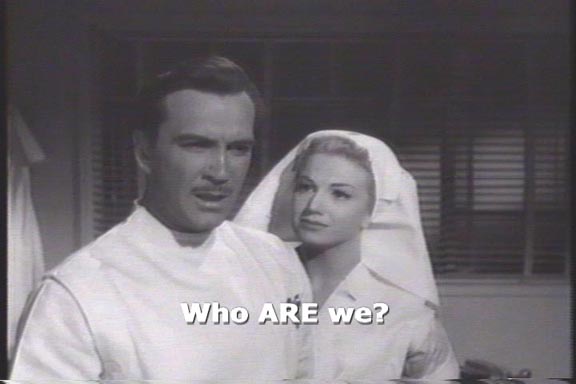

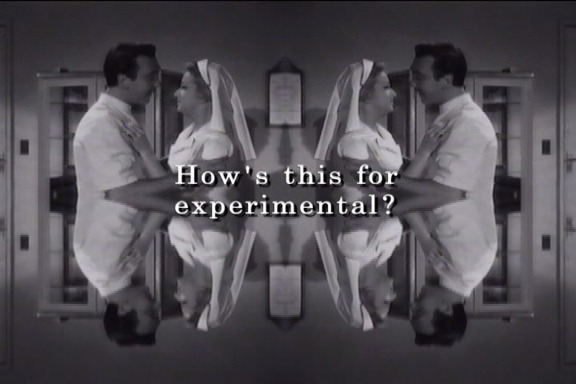

The plot in Uso Justo is less important than the film’s subtexts. In a nutshell, the film is about a doctor and a nurse’s awareness that an experimental film is being made in their town, which happens to be called Uso Justo. Another sidenote: “uso justo,” roughly translated, means “fair use”; by now, you’re probably starting to get a sense of the way this thing is layered. I won’t ruin the film by delving too deeply into what happens, but Miller builds many more overlapping layers of story and effect. For instance, a young girl named Norma, who is the hospital’s current “Make-a-Hope” child, wishes to see butterflies, even as the nurse reveals it has been her lifelong wish to be in an experimental film. Later, the nurse expresses her fears to the doctor that the artist will never finish the film, to which the doctor replies: “But aren’t we on screen right now? Doesn’t that prove the film is finished?” When the nurse reveals she has heard a rumor that they are found footage, and that the artist couldn’t “afford to shoot his own film,” the doctor is dumbstruck. The music swells, and the doctor turns away: “Who ARE we? And why?”

The simplicity of the concept—take something and rearrange to make something new—disguises the complexity of Miller’s act of creation. Although they are forced to condense what they know and believe down into the strictures of a given source, what artists like Miller work with is the world of ideas. Limitations of this sort are what force us to find true creativity; after all, life itself has a limiting, limited scope. And while it is human nature to wish for more—as both Norma and the nurse do in the film—it is also human nature to make lemonade out of lemons, so to speak, as Miller has done here.

There’s a lot more humor in the movie—that I won’t give away—and a lot of beauty as well, in the pale, pastel-gray tones of the original footage (circa late 1950s-early 1960s), in the beautiful and subtle light of the scenes (light not often found under the bleaching kliegs of modern films), and in the powerfully subtle final scene. Miller also is true to his experimental roots at one point in the film—taking us for a moment out of the drama and into a beautiful abstract montage of images and sounds that deepens the film as a work of art and humor even as it advances the plot. The story reaches a peak a few moments later, as a riotous crowd of townspeople are fed up with the omnipotent (and absent) filmmaker, whom they think has gone crazy. “We’re not going to sit by while some video artist renders us pawns in his pseudointellectual claptrap,” someone screams before the crowd rushes to the railroad tracks to find him. “Let’s go shove that camera up his experimental ass.”

In the end, unlike the townspeople, we should consider ourselves lucky—very lucky—even to see Uso Justo, as Miller himself (as he reveals throughout the film) barely managed to scrape up enough money after he completed editing to have the film released (film being a rather expensive medium on the whole). It was only after Miller held a benefit screening of the film at Outsiders & Others gallery this past January (where nearly 100 people attended on one of the coldest nights of the year), that he had enough money to submit it to a few film festivals. And at the risk of sounding a bit too Hollywood, I’ll point out that in the first two of the festivals Miller entered—the Ann Arbor Film Festival and the Humboldt Film Festival–Uso Justo has deservedly won “Best of Fest” awards. Be advised, struggling ones: sometimes the life of an artist does have a happy ending.

Coleman Miller’s film Uso Justo runs as part of the “Minnesota Mavericks” program at the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Film Festival on Wednesday, April 13, at 7:15 pm at the Bell Auditorium.