In Practice: Poet Sun Yung Shin

Lightsey Darst continues her candid series of conversations on practice with poet Sun Yung Shin. On the docket: immigration and identity, the pernicious myth of the American meritocracy, and the latent witchery of words.

Sun Yung Shin 신 선 영 is the author of the forthcoming books in 2016: prose collection Unbearable Splendor from Coffee House Press and essay anthology A Good Time for the Truth: Race in Minnesota from Minnesota Historical Society Press. Her poetry collections Rough, and Savage and Skirt Full of Black were also published by Coffee House Press. She co-edited the anthology Outsiders Within: Writing on Transracial Adoption and is the author of Cooper’s Lesson, a bilingual Korean/English illustrated book for children. Her awards include a McKnight Fellowship, a Bush Foundation Fellowship, and two Minnesota State Arts awards. She lives in Minneapolis.

What is work?

Sun Yung Shin

Work is something a person does to create something of value to themselves or other people. I think of the Greek word poiesis. Wikipedia defines it as “Poïesis (Ancient Greek: ποίησις) is etymologically derived from the ancient term ποιέω, which means “to make”. This word, the root of our modern “poetry”, was first a verb, “an action that transforms and continues the world.” I also like to think about the word techne, “”Techne” is a term, etymologically derived from the Greek word τέχνη (Ancient Greek: [tékʰnɛː], Modern Greek: [ˈtexni], that is often translated as “craftsmanship”, “craft”, or “art”.”

Lightsey Darst

That first sentence is very clear and fantastically validating. Thank you on behalf of everyone to whom to this definition brings dignity. (I imagine it’s not just me.) I love this definition so much that I just checked it against my dictionary, where I find

(1) activity involving mental or physical effort done in order to achieve a purpose or result; (2) such activity as a means of earning income; employment; (3) a task or tasks to be undertaken; something a person or thing has to do (New Oxford American Dictionary)

This definition—in comparison with yours—gives no autonomy or dignity to the worker. The worker’s right to decide what is valuable is completely missing, as is the idea that work is creative.

Sun Yung Shin

I must give credit to Mark Nowak, who taught me about the concept of the culture worker. Since then I’ve continually seen our work as poets through the lens of labor, as well as through other lenses, of course. He is amazing.

Lightsey Darst

How much of your work is redefinition? I’m thinking of the etymology you trace above, which teaches us that poetry can be work and work can be poetic—or how these poems from your forthcoming book ring changes on strangeness and intimacy—or, more generally, the way you have of turning words and phrases around so that we can see what might be behind them.

Sun Yung Shin

That is an interesting question. I don’t think of it as redefinition, although I suppose I could. I think about it as investigations into the archeologies of words and often some kind of attempt to get into the shadow words. So much of our governmental-speak globally is double-speak; or, what did Orwell call it in 1984? Newspeak. The three slogans of the party:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

Like a lot of immigrants, I have a complicated relationship with the English language. I’ve always loved words, like probably all poets, from a young age, but like a lot people of color or working class people, it never occurred to me that I could be a writer. My adoptive mother is Polish-American and her mother spoke Polish and English. My adoptive father is Irish and German (Alsace Loraine-an) and his father spoke German. I was raised in the Roman Catholic Church, which has lived in many languages—Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic. Because my mother made sure that I tried different things as a child, I did ballet starting at age four, where I was introduced to French as the language of the body. I took piano starting at age five or six, where I was introduced to Italian as the language of time, mood, volume, music. Musical keys were named after alphabet letters, but only up through G. Science class possessed Greek (hydrology) and Latin (aquarium). Then there were British books with their sly “s”s instead of “z”s and glamorous “flavours” instead of practical, shorter “flavors.” Science class also spoke in a numerical language of the Europeans—the mysteriously rational metric system, but at home and in stores we spoke a poetic and human-scaled language of cups, feet…reading Black Beauty introduced me to more body language—a horse and how many hands tall…It’s endless, but those are some major frameworks of my childhood. And of course, the Korean (Hangeugo and/or Choseunmal, the names of which are written below vertically) —

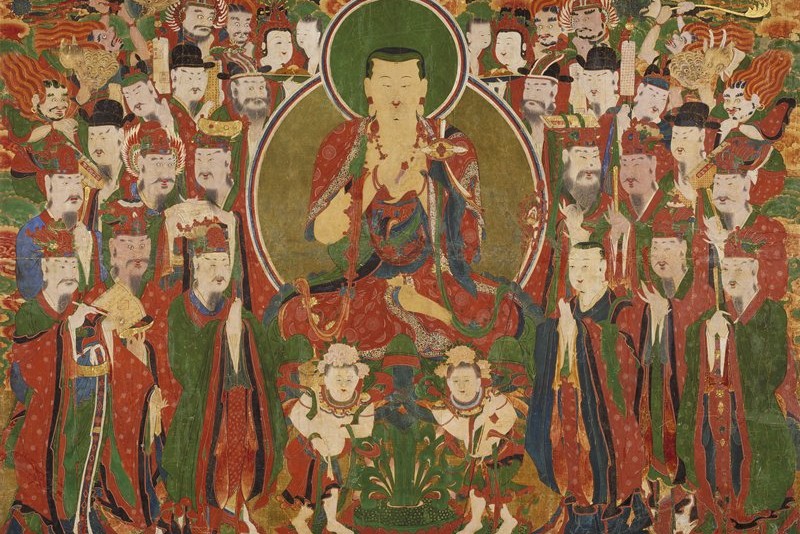

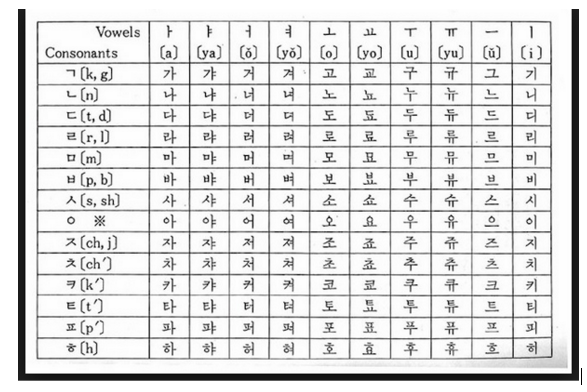

— and the Korean writing system (Hangeul. Here’s Hangeul in the McCune-Reischauer (instituted in 1937 by two American scholars, George McCune who was at Berkeley and Edwin O. Reischauer who was at Harvard) system, which was in place when I was born:

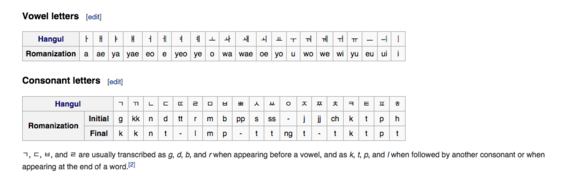

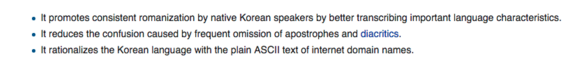

In 2000, the Korean Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism changed the Romanization to what is called Revised Romanization, which eliminated diacritics and apostrophes:

Reasons given:

And I can’t leave out Hanja, which is “is the Korean name for Chinese characters (hanzi). More specifically, it refers to those Chinese characters borrowed from Chinese and incorporated into the Korean language with Korean pronunciation” (Wikipedia). So my name on my Korean passport is written “in Chinese” as well as “in Korean.” Then there’s the fact that Korean went underground from the time Japan annexed the Korean peninsula until after the Korean War—Koreans were required to take Japanese family and personal names and had to go to school in Japanese. Koreans often took Japanese names that were subversive in some way, seemingly unbeknownst to their colonizers.

The seductive but banal language of advertising was the only poetry in my life, really, until I started writing poetry in 1998 or 1999. I would read the copy on the back of shampoo bottles while in the shower over and over, marveling at what I later learned was called alliteration, iambic pentameter, assonance.

As an Asian American who speaks English without a “foreign” accent, as with all others like me, our ability and perhaps even right to speak English is often called into question by complete strangers, who feel entitled to challenge our belonging and our fluency. We’ve all been told at some point or another or many points to go back where we came from. Where I come from is a country that was invaded by Russia in August of 1945—Japanese surrendered to Russia in the north and to the U.S in the South. The Korean War, 1950 – 1953 but ongoing as a cold war with no peace treaty signed, ended with a cessation of hostilities in which the U.S. was centrally involved. The beginning of the Armistice Agreement, which was signed on July 27, 1953, starts like this, “Agreement between the Commander-in-Chief, United Nations Command, on the one hand, and the Supreme Commander of the Korean People’s Army and the Commander of the Chinese People’s volunteers, on the other hand, concerning a military armistice in Korea.” There are currently about 30,000 American service members stationed in the ROK (Republic of Korea, “South Korea”) and John Kerry recently pledged in August to send 800 more. The reason 200,000 Korean child citizens were displaced to other nations in the global North/West (Europe, North America, Australia) since the end of the Korean war is because of U.S. servicemen abandoning (or not knowing about) their mixed-race children with Korean women. Those mixed-race children and their mothers were pariahs, and many of the former ended up on the street. Thus began a 60-plus year program of what some call child exportation, even as South Korea evolved to become the 11th largest economy in the world.

So back to your question—I do feel a strong relationship to individual words as objects, as human constructions often parading as natural, unquestionable, that need to be turned around and examined, carefully sometimes, as if they’re dangerous caged animals or ticking bombs. Language is obviously a major tool of those in power or those seeking to dominate others. As you know, poets are endangered in many places as truth-tellers and people whose minds cannot be controlled. In this way, I think of poets and journalists as very close varieties of the same species.

I find every word suspect, and many words unbelievably beautiful, potent, charged, magical. I live within a master “we” (e.g. “our forefathers”) in America that often doesn’t include me or doesn’t seem to. As a naturalized citizen, I do take on the responsibility of everything the U.S. government does in the name of “Americans” and “U.S. interests.” How can any of “us” not? U.S. citizenship is of course a tremendous privilege and affords mobility that many on the planet do not have.

Since the early days of my working with poetry, I thought of my writing, in part or sometimes, as a way of participating in larger conversations that exclude or objectify me or people who look like me or my communities, including the global community of girls and women.

____________________________________________

I find every word suspect, and many words unbelievably beautiful, potent, charged, magical. I live within a master “we” (e.g. “our forefathers”) in America that often doesn’t include me or doesn’t seem to. As a naturalized citizen, I do take on the responsibility of everything the U.S. government does in the name of “Americans” and “U.S. interests.” How can any of “us” not?

____________________________________________

Lightsey Darst

Witness this recent Facebook status, in which you pull together Harper Lee, police brutality, the Confederate flag, and all the rest of last summer’s stew:

Go set a Watch / police state / book club / billy club / Boo Radley / spook ghost haunt / Rudyard Kipling / yellow peril / railroad coolie / rising ocean / melting glacier / filthy water / closed Gap stores / four bankruptcies for Donald Trump / sweat shop / Go set a Watch by the next stop / frisk / arrest / murder / death penalty / execution / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / Go set a Watch / / / Flag / Shroud / Flag / Shroud / Flag / Winding Sheet / Crib / Cradle / Veil / White at Last / Go set a Watch

Even for a poet, you have a special sense for what’s under the skin of the language. How does that work?

Sun Yung Shin

I think I tried to start answering this above (I could write a few books about my relationship to the Korean orthography, its role, possibly, in allowing Koreans to become the fierce pro-democracy organizers that they are) but as far as this status, I wrote it because I was very frustrated at all the fawning over Lee and the sacred quality of the hype around the release of Go Set a Watchman. I don’t even know what that phrase means so it took on a strange untranslatable quality for me. I also remember To Kill a Mockingbird as condescending to black people, but I haven’t read it in forever. I think both my children were assigned to read it in middle school. It continues to be a staple in the American K-12 system. I suppose I should read it. Most of my students have read it, or had it assigned to them. On the internet, including Facebook, I saw a lot of white people who had been largely silent on all the catastrophes that have been occupying American people of color and especially Black Americans go crazy over this Harper Lee book. It was upsetting. No people of color that I know of were going crazy over this new book. The divide between what my friends and colleagues of color care about online and what white people and colleagues care about (post, repost, comment on) online often seems vast. I’m certainly not the only person of color who has noticed this. Something I was keying into in the “Go Set a Watchman” phrase is surveillance, “watch” and also sic-ing something on someone, “set a dog on you,” and the sentence as a command is somewhat ominous, I felt. The phrase “White at last” is about the feeling that if only we “non-white” (I hate that descriptor, probably for obvious reasons…) would either a) die b) go away forever c) just act like white people, then everything would be great. “Talking about race just divides us,” etc. We are constantly fighting against being silenced. We are constantly shamed for talking about our realities. We are constantly seeing ourselves on the small and large screen being incompetent, being criminals, being animal-like, being evil, being dumb, being robotic, sacrificing ourselves happily for the white hero, etc. etc. etc. As Kazim Ali recently said in an open letter to Aimee Nezhukumatathil regarding Best American Poetry, “I can tell you this: when you talked about how hard it is to walk through the world with the name “Nezhukumatathil” it struck a chord in me. Not just because our names are hard to “say” properly but because that is just a metaphor for our lives. Our lives are hard to ‘say’ properly. That is what we do in literature.”

What’s the best loss—for yourself or for anyone?

Sun Yung Shin

Loss of the myth of American meritocracy.

Lightsey Darst

Preach.

That meritocratic myth, though—it looks different depending on who you are, right? Or rather, what you see once you see through it might look different.

To me, a middle-class white kid, the myth meant class didn’t matter. Or rather, class didn’t exist. Talent and intelligence existed, and with those, you’d succeed. Oddly, hard work wasn’t part of the picture, and neither were people skills. White privilege in action? Or white delusion. . . it’s hard to talk through this muddle of things I thought when I was sixteen, but damn, that meritocratic myth worked beautifully: it made me think I was superior to other people while separating me from the tools that I could really have used. What was it like for you?

Sun Yung Shin

Hm. I have to say that I had no idea of any future for myself. In some ways I still don’t. It’s a white nothingness. I live in some ongoing now that isn’t really all that effective in terms of life planning. Or at all effective, I guess I should say. I don’t really understand it (it seems defective), but even as a kid, I followed my interests but did not envision a future. I think partly that’s because I didn’t know any adults like me, not just racially/ethnically, but who were insanely voracious readers, who were kind of weird and into Norse mythology and Russian novels at the age of 15, etc. I had no concept of becoming, for example, a professor, because I did not know any; I did not even know anyone who had been to college except my teachers (presumably, although they never talked about it) and my mother’s brother, who was a very wealthy corporate lawyer (and a white man) who had gone to Dartmouth (where was that, even?) on a basketball scholarship, was a Rhodes scholar at Oxford with Bill Clinton, and came back to Chicago with a British wife. That didn’t seem to have much to do with me. Plus, there are so many careers now that didn’t even exist when I was growing up. But no one ever suggested any kind of job to me my entire life, truly. No one encouraged me to be a writer or a journalist or anything professional, or not that I can remember. I was a spelling bee kid, but no one thought that that facility might predict some kind of word-based career. I probably just looked like any other Asian “robot” smart kid or classical music grind. But I also played softball and basketball and, later, tennis, and didn’t fit in there either (just like in ballet class), but I didn’t care. No one seemed to really care about girls in sports anyway, except our coaches and parents, bless their souls.

I know I was inundated with the message that I was lucky to be in America. That I would be a) dead b) a prostitute if I had remained in Korea (in that order, a dead prostitute…or maybe a zombie prostitute…although this order was not funny when I was a kid). Someday I will definitely be dead, fulfilling my doppelgänger’s bad luck. Korea, then described to me as a “Third World country,” was a loser in the global meritocracy. Clearly, it had no merit. Its people were losers, they couldn’t even raise their own children. So where did that leave me? It seemed, in some ways, that anything other than being a prostitute, or dead, was a big “step up” for someone like me. So, in that sense, I had more in common with the very poor of this country than with the rest of my extended family, which was blue collar and included large Catholic families; my cousins were Chicago cops and managers at McDonald’s. The only thing I could imagine, because it was almost the only type of profession in front of me, was being an English teacher. I loved English class, I liked to play school with my best friend Allison, and my English teachers were the smartest, most freethinking people I knew. I had zero idea of what kinds of careers were available to people who loved words, such as creative writing or journalism or editing or publishing or speechwriting or advertising/marketing or professor-ing… I don’t think I even asked myself or anyone that question. It just didn’t exist for me.

I don’t know if that even addressed your questions!

Lightsey Darst

More than addressed them—more like dressed them down! I feel like I want to go back and replay high school from the perspective of some of my friends now.

What’s the best drink you ever had?

Sun Yung Shin

Soju shared with a Korean political fugitive and an incredible group of Korean and Korean American pro-democracy activists inside a labor union headquarters—right next to a police station—in Seoul.

What gives you hope for real change, and what real change do you hope for?

Sun Yung Shin

That the U.S. will be a(n ethnic) minority-majority country soon gives me hope. The real change I hope for is the end of white supremacy and the extinguishment of rape culture (including all forms of violence against girls and women) on the planet.

What is the most important scientific principle?

Sun Yung Shin

The second law of thermodynamics.

Lightsey Darst

I thought at first you were talking about the law that says that nothing can be created or destroyed, a concept I find immensely reassuring. My grandmother is no longer alive, but everything that went to make her—even her quintessence—is still here, incorporated into new beings.

However, that’s the third law, not the second. The second states that entropy can only increase over time. Whether you find this reassuring depends on how you feel about order, I suppose: order meaning something like organization, with its implication of hierarchy. I want to connect this with your answer immediately above, with the end of the white majority. . .

. . . and, if it’s not too much of a leap, I want to connect it with something I’ve noticed in your poetics, which is that you are not afraid of a new word. Some poets are. I find it difficult to use words freshly learned, because I can’t give them the lived-in feeling I’m after. The result is a smaller working vocabulary. You, on the other hand, really swim in the dictionary! How do you do that—how do you welcome that potential chaos into your writing?

Sun Yung Shin

Agreed, I also find it immensely reassuring!

I’m not sure that the end of the white majority is really about entropy, but some kind of evolution for sure. I will have to see how things develop, but I have hope for a more fair society, even though it doesn’t seem like much is happening right now, structurally, but people of color and white people alike who are dedicated to positive social change are, to some degree, being heard more. Or at least we are taking up more space (virtual space and public physical space), which I love.

Hm. I like that image of swimming in the dictionary, kind of like Harryette Mullen’s Sleeping with the Dictionary. Sometimes I think of poetry especially as spell-ing — making spells, trying out various kinds of magic to see what will happen. Words, and letters, are things. There some kind of radical equality there, in English, in the same finite 26 letters, a small set of things, being able to make a virtually infinite number of “spells.” What can we conjure? Words should be afraid of us, the poets, because we can dig them out of their graves and catacombs and burial mounds, pry them from wall friezes and off of lintels of grand buildings, and make them walk and do unforeseen work…

Editor’s Note: Lightsey Darst is conducting a series of interviews with artists, writers, and other interesting people. Look for repeating questions across the series. If there’s someone you’d like to see her interview, please let her know: lightsey(at)lightseydarst(dot)com.

Lightsey Darst is a writer, critic, and teacher based in Durham, NC.