Making Nowhere Into Somewhere

Writer Stephanie Ash profiles the artists of the Rural America Contemporary Art (RACA) group, who are reinventing art made by country folk -- and there's not a hay bale-painted saw in sight.

BEFORE I MOVED THERE, I ASSOCIATED MANKATO WITH DRUNKEN DEBAUCHERY. I learned this from Little House on the Prairie, and from my high school best friend who did her undergraduate degree at what is now Minnesota State University, Mankato.

I did not associate Mankato with contemporary art. In fact, until recently I did not associate anything in rural America with the term. (And I hail from such parts.) Instead, when I thought “contemporary art,” I thought of that scene in Crocodile Dundee, where the cosmopolitan woman writer takes Dundee to a New York City gallery party packed with tuxedos and cocaine. The woman writer drinks a martini. Her dress is backless and side-less. Everyone dances to New Wave.

But there is a new movement afoot.

MSU art professor and contemporary painter Brian Frink didn’t start it. He just named it and collected it in one place. Bouncy, good-natured, and a bit of a schemer (he convinced his wife they should buy an abandoned poor farm south of Mankato — and then raise their kids there), Frink started to notice something peculiar in his students: The drive to leave home and strike out for New York or other large “art cities” to embark on a career seems to be dissipating.

And he noticed something else: Artists he knew were connecting with each other, with audiences, and even with paying customers via Facebook.

The two, he believed, must be related. Unlike Brooklyn in the ’80s, where Frink rented a 2,000-square-foot loft/studio for $150 a month, today’s young artists are priced out of the famous art cities. What young person can afford studio space in San Francisco, New York, even Chicago? Most of them can’t even afford to rent an apartment there. Plus, the critical interaction and cross-pollination of ideas on which contemporary art relies — once the domain of big urban populations — makes its home on social media now, and can be hosted by anyone with a domain name.

“Last winter I had a couple of beers, and that phrase came into my head,” Frink tells me during a hangout session. (We are buddies.) “RACA!” he shouts. “It sounded bold and big and brash, so I made a Facebook page.”

Suddenly, there were hits. “Gobs and gobs of hits,” Frink says. Within weeks, the Rural America Contemporary Art Group had more than 400 artist-members from across the country, all posting their work.

There wasn’t a single hay bale painted on a saw in the bunch.

The RACA show in St. Peter

And what does an artist do, once a community is coalesced? After writing a manifesto and coming up with the group’s slogan — “Making somewhere out of nowhere” — Frink organized the first Rural America Contemporary Artists exhibition, at the Arts Center of St. Peter. It opened on December 10 and will be on view through January 8, 2012.

While I didn’t see any side-less dresses or cocaine at the reception, the sunny gallery was packed with friends and artists and students, meeting and greeting among the work. For this first RACA showing, Frink tapped his Mankato-area friends — an eclectic, accomplished, and proudly “rural-contemporary” bunch. Among the works are mixed-media abstracts from Liz Miller, who was just named one of 25 artists nationwide to receive a sizeable grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation. She and her husband, artist David Hamlow, who’s also showing work in the exhibition, live in tiny but powerfully named Good Thunder. You’ll also see sculpture from Lisa Bergh, who (with her husband Andrew Nordin, who also has work in the show) runs the gallery ARThouse out of the family home in the ironically named New London. And then there’s collage by mixed media printer Erik Waterkotte, whose dystopian light boxes (one featuring a moving Mick Jagger) are about the last thing you’d imagine at a showing of “rural” art.

Also on view are whimsical, tongue-in-cheek paintings and drawings from Diana Joseph and David Clisbee (both also are buddies of mine). Clisbee and Joseph, writers first, particularly represent the spirit of RACA, Frink says. “They are [visual art] outsiders creating across mediums,” he says — and inclusion and border blurring is what he hopes RACA fosters. Joseph’s 2009 memoir I’m Sorry You Feel That Way was called “pee-in-your-pants funny” by Entertainment Weekly. She spent last summer in Los Angeles with Meredith Viera’s production company pitching a TV show based on her and David’s life raising their 9-month-old son and her 19-year-old son. And both those projects, and her paintings, were made in little ol’ Mankato, in the same house Clisbee completed is first book of poetry.

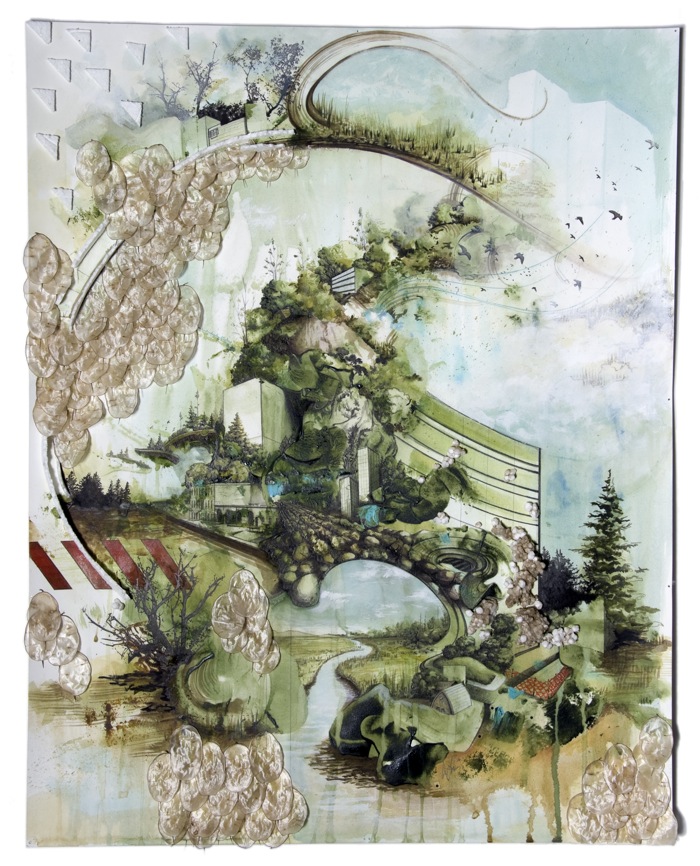

And there is work from artist Gregory Euclide, the man behind the cover art on Bon Iver‘s Grammy-award nominated album. Euclide’s work sells for thousands of dollars, undoubtedly making him the most successful artist living in LeSueur if you don’t count the Jolly Green Giant. He teaches high school art there as well, to rural kids a lot like himself at that age: “Because we were rural we felt an especially strong desire to devour this thing called ‘culture,'” he wrote me. “We would try very hard to get to the city to buy music, but the days back home were filled with the making of forts in the woods and walking the fields.”

________________________________________________________

“‘The house of fiction has many windows,’ and visual and contemporary art do, too.” But too often the contemporary art ‘window’ only acts as a mirror that reflects back on itself so self-referentially, it loses relevance to nearly everyone outside its narrow frame.

________________________________________________________

The Importance of Edgelessness

That tug for “culture” but need for space defines many of RACA’s artists, whose collective work (at the show and as seen online) has a noticeable lack of framing – of either the literal or metaphorical variety. It’s an eye you don’t often get in, say, the New York or San Francisco scenes, where contemporary visual art, Frink says, often comes from “the corporation — the international art scene centered on the coasts and a select one percent.”

Diana Joseph quotes the novelist Henry James to explain her take: “‘The house of fiction has many windows,’ and I think that way about visual and contemporary art, too.” But too often, RACA artists say, the contemporary art ‘window’ only shows that one-percent view Frink’s talking about, which isn’t very relevant to rural culture. Or worse, it acts as a mirror that reflects back on itself so self-referentially, it loses relevance to nearly everyone outside its narrow frame.

And in today’s boundary-busting age of the networked Web, “people who live in this world and make art here might be making work that is more metaphorically appropriate than urban people,” Frink says. “When I lived in New York, people made art looking through windows; the artwork always had this kind of frame around it, created by windows, doors, and architecture. Nature is always framed by architecture in urban spaces, so the art made there refers to that. Here in rural America, there is an edgeless notion to the world we live in; I think that is more appropriate in the age of the Internet.”

Frink himself has moved past his usual shape-driven, large-scale paintings the past two years and taken to making large-scale paintings of people’s pets. His giant cat portrait on view at the RACA show is warmly provocative in the exact way he describes above, with a gentle reverse irony that comes from a lack of boundaries between audience, subject, and artist.

Lisa Bergh’s work has changed too, since she and Andrew Nordin moved to New London from Milwaukee. “I’ve been more productive with more space,” she tells me. “I make more art here, and stronger connections.” And ultimately, that’s what RACA is really all about. “It celebrates that there are these people living here,” says Liz Miller. Says Euclide: “It offers rural artists a platform for appreciation and support. It shrinks the distance between individuals. … Space can be isolating if one does not have an avenue to connect with similar-minded individuals.”

And it’s a welcome thing, to live in congenial surroundings that require only modest means to get by — art is hard to make if you can’t afford the studio space.

________________________________________________________

Noted exhibition details:

The first ever Rural American Contemporary Art (RACA) group show is on view in the Arts Center of St. Peter, Minnesota through January 8, 2012. Participating artists: Karl Unnasch, Michon Weeks, Liz Miller, David Hamlow, Gregory Euclide, Benjamin Gardner, Alan Montgomery, Lisa Bergh, Andrew Nordin, Diana Joseph, David Clisbee, Erik Waterkotte, Brian Frink.

________________________________________________________

About the author: Stephanie Wilbur Ash lives in Mankato and in Minneapolis with her husband, author and creative writing professor Geoff Herbach. Her hometown, Oelwein, Iowa, is the subject of a New York Times bestseller, but don’t let that fool you. The book is called Methland. Her own novel about the place is currently seeking a publisher. There’s a little less meth in it than the other one.