News to Her

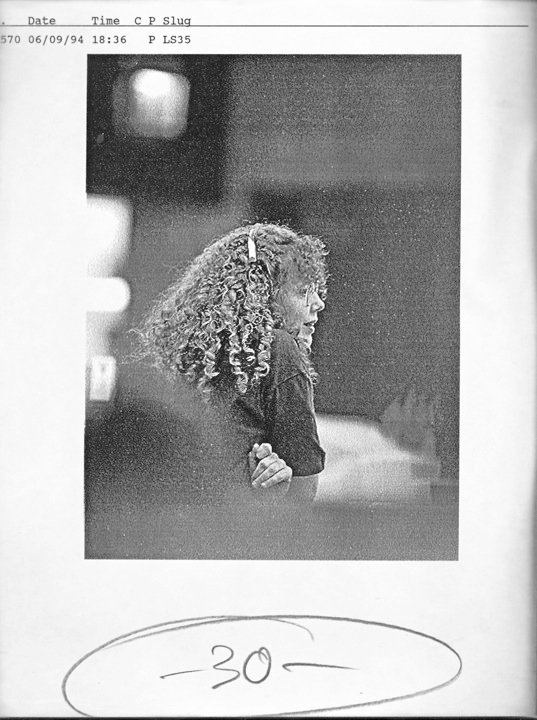

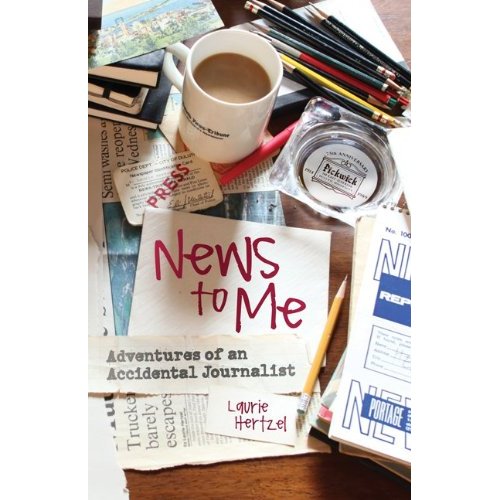

Ann Klefstad's informal review and talk with Books Page editor Laurie Hertzel about her upcoming book "News to Me: Adventures of an Accidental Journalist," out this summer from University of Minnesota Press.

NEWS TO ME: ADVENTURES OF AN ACCIDENTAL JOURNALIST IS A CAREER MEMOIR BY Star Tribune books editor Laurie Hertzel, mostly about her life at the Duluth News Tribune. It’s an amusing and enlightening window into a beautifully drawn, very particular world.

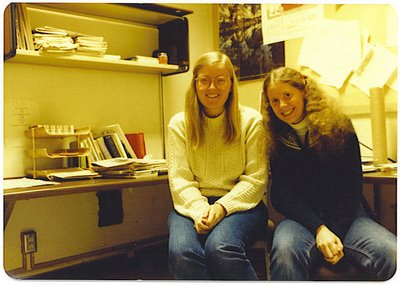

The title’s a little misleading: it’s true that Hertzel didn’t go to J-school (journalism school, in the lingo-loving jargon of newspaper staff), but she entered newspapering young; working jobs from newsroom clerk to librarian to copy editor to reporter to editor, she took to the milieu like a duck to water. If her career was an accident, it was a lucky one.

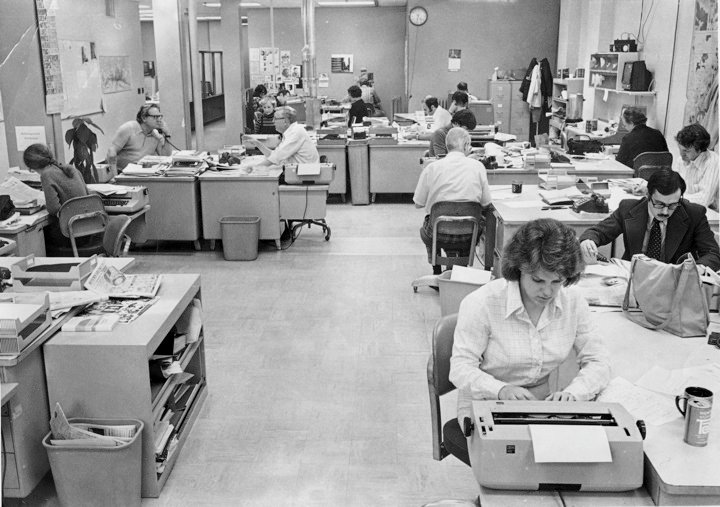

Salty characters abound in this charming, picaresque tale of the shy girl growing up mentored by the smoky, boozy, old-style reporters that populated the newsrooms of the ’70s. Her loving portraits of these denizens never fail to charm: “the jittery religion writer who wore loud plaid pants and a wide white vinyl belt and once dropped his false teeth on the floor,” who explained to the young reporter, kindly, the ways of the newsroom; or the business editor with a “luxurious swoop of white hair and a ratty beige raincoat that he wore winter and summer,” who brought her books from his collection.

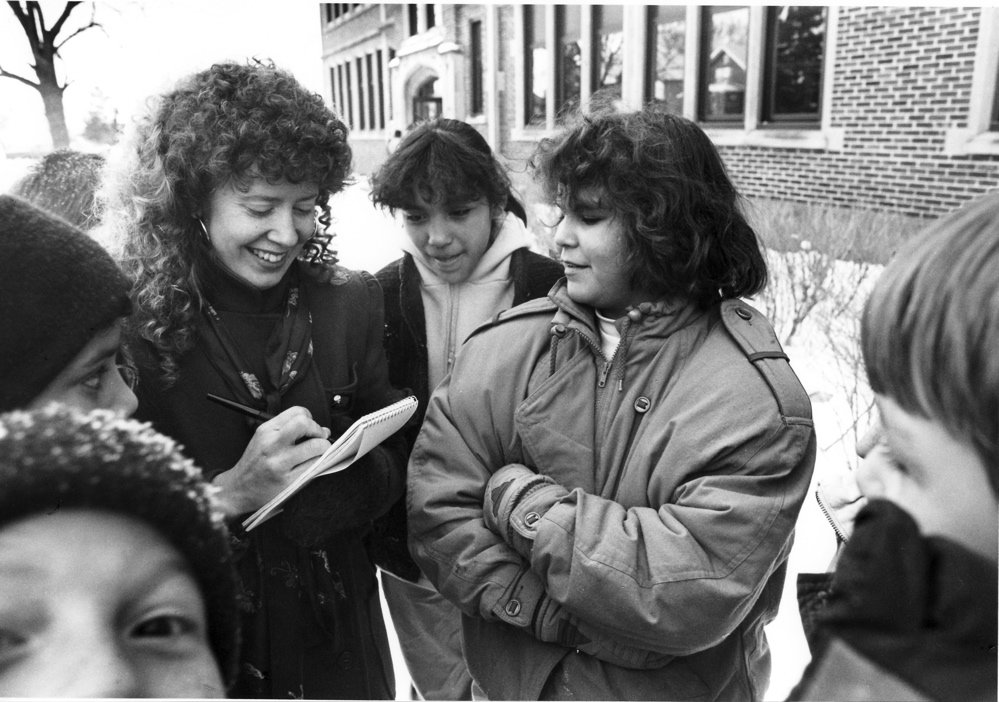

Hertzel tells also about the entry of bright young women into the then male-dominated profession. These women changed the nature of news, and she was one of them, although the continual self-deprecation she practices in the book obscures this at first.

The center of the book — the hinge of the life it depicts — is when Hertzel stumbles on features-writer gold: the story of the Finnish Americans who emigrated to Stalin’s Russia out of belief in a Communist paradise, and whose hopes were cruelly betrayed by the Great Terror.

When in August of 1986 some Duluth citizens travel to Petrozavodsk in the USSR to establish a sister city relationship, Hertzel wangles her way into the trip, managing to convince her cheapskate editor (some things never change) to finance her ticket.

When the Duluth contingent got off the train in Petrozavodsk, they encountered a group of elderly people on the platform. The Russians began asking, in English, about familiar Duluth scenes: “Are the hills still green? Does the Aerial Bridge still go up and down?” Hertzel was astonished: “I stared at them and tried to figure out who they were, why they were speaking English…. I had completely forgotten Erkki Leppo and his tales of American Finns in the USSR. I touched one of the old people on the arm, to get her attention. ‘How do you know the Aerial Bridge?’ I asked. The woman smiled at me. ‘I was born in Cloquet,’ she said.” After a wonderfully written account of her Russian train journey, this scene blossoms.

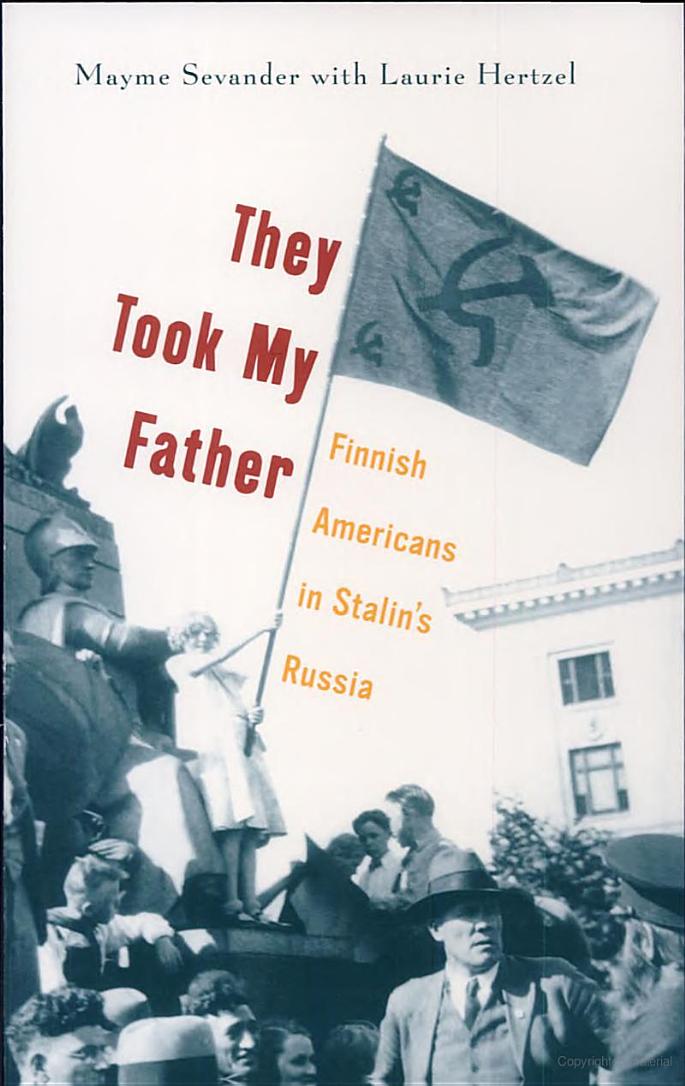

Much of the rest of Hertzel’s memoir concerns her subsequent adventures in Russia, Finland, and the U.S. writing the book that resulted from the Petrozavodsk trip: They Took My Father, authored in collaboration with Mayme Sevander, one of the Russian Finns whose father was killed in a purge. As News to Me moves away from the jaunty tale of a girl reporter in an old-school newsroom, it both deepens and slows — but the story, an individual one now, remains engaging.

Upon finishing her book on the Russian Finns, Hertzel returns to the Duluth News Tribune, but only after a blackly comic scene in which the head of the UMD English Department, a miracle of pompous fatuity, refuses to discuss a practicable way for her to get her B.A. Back at the DNT she works for “the man with three first names,” editor Bob Jodon, but her days at the paper are numbered. How can you keep a girl home in Duluth after she’s seen the world?

In the mid-1990s she leaves Duluth for Minneapolis, where she works with Minnesota Monthly and then the Star Tribune.

News to Me wraps up with a refusal to muse on the future of journalism: “Me, I keep my head down, do my work, enjoy the hubbub and bustle of the Daily Miracle, fervently hope it lasts.” This is the voice of a good reporter — observe, don’t comment or interpret, do the writing as well as you can, and keep showing up. The virtues are humble but essential, and as difficult as anything in the world.

This kind of journalism may be endangered in the age of blogs and blather; I do hope it lasts, too.

________________________________________________________

A Q & A with News to Me author Laurie Hertzel:

Of all the stories you’ve written, which is the one you remember best?

One for the Duluth paper, a story I wrote about Ruth Niskanen coming home. She was born on the Iron Range, and I met her in Russia. After the Mayme [Sevander] book came out [They Took My Father, 2004, about Finnish Americans who emigrated to Stalin’s Russia], Finnfest happened in Duluth — that’s a national festival, but it moves around the country, and that year it was in Duluth. A handful of [Minnesota-based] Finns raised enough money for some of these Finns in Russia to come home to visit.

Ruth Niskanen came, and Ernest Haapaniemi. They stayed with me in my house; they had my bedroom and I slept on the couch. All Ruth wanted was to see the house she grew up in, out in Palo. And I went with her. It was so moving … The house was abandoned, people had moved out in the ’70s, I guess, so there was some old furniture in the rooms, just old and junky. She walked through the house, she remembered everything about the day they left — there were still chickens in the yard, she remembered the door closing with a click. This was the house her father had built with his own two hands. Ernest ran his hands down the doorpost, saying, “Look, it’s still straight. ” She was upstairs, looking out … it started to rain. It was so sad.

That was the first story I wrote that won a national prize.

Are there stories you wish you hadn’t written?

Well, now that’s hard to answer, because I always was pretty serious about the stories I wrote. I got a lot of stupid assignments, everyone does, but I always tried to make something good out of them.

But I deeply regret the way I handled a certain story. I had worked out a series of stories with another writer about being gay in Duluth. This was the mid-80s, and I didn’t know anyone who was gay — I didn’t know anything about it. I had wonderful sources, but people had to be anonymous. It would be hard for young people now to know just how afraid people were then. One of my sources was a lesbian couple; they had been so kind to me, they made me tea, I visited them in their house by the lake. They insisted on anonymity — everybody did. And I did that — but I included a few too many details and their families figured it out. [After the story came out] they sent me a note and told me.

I don’t know how things worked out for them, maybe it was okay, but I always felt really bad about that — like I betrayed them, when I intended the opposite.

How do you think young journalists now differ from those starting out when you began as a reporter at the DNT?

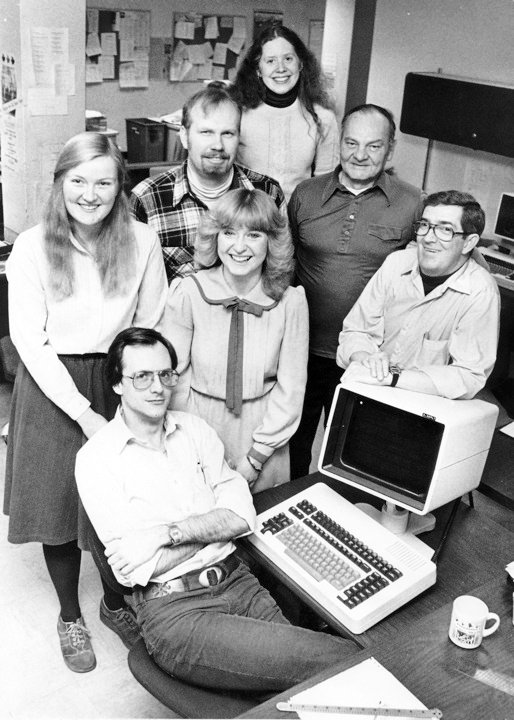

The work is essentially the same, but it looks different. I look at the new reporters now, and they are so nimble and adept at Twitter and blogs and getting things off MySpace — all the multitude of ways of gathering information. Actually, I have worked with some young reporters in the past — not at this job — who were less inclined to leave the office and actually talk to people. They wanted to find things on the Internet. But, mostly, the skills are the same but the tools are different. It’s still about gathering the information. I feel that writing standards are slipping, because you’re asked to do so much now — maybe you do a video standup, pound out the story, do a blog item. But [in the midst of this] there’s an ebb and flow of emphasis on writing the good tale. Sometimes we have to bring it back again. All these different means of communication do fragment your attention. It’s hard to immerse yourself in one powerful thing, because you have to be also doing all these other things.

You’ve now arrived at the “Books” page of the Strib — does this job feel anything like coming full circle, from your first job in Duluth’s Carnegie library to the books page?

It all comes back to books, constantly. My father was an English professor, and we grew up in house surrounded by books; we got books for birthdays. My father, when he was in a particularly good mood, he’d bring us down to Kreiman’s Bookstore downtown and let us pick out a book. But the library work [shelving books] wasn’t very creative. This is different, it’s creative; it’s not circular, but the work I’m doing now values the same thing.

And what’s next for you, another memoir?

I’m not planning a book of later years, because I’m still living them. I might get fired or make publisher or go off to the New York Times! What interested me in writing this book was how I went from being that very shy person, who didn’t even know how to drive a car, to working in Minneapolis. I think of it as the world’s longest coming-of-age tale. Usually coming-of-age stories last a few months — this one takes 20 years.

I am thinking of writing another book, but maybe more about Duluth.

What do you see ahead for newspapers?

I really don’t think newspapers are going away. I don’t think we live in a world where people don’t want a newspaper. I don’t like that kind of speculation, because it’s always dire. Our newsroom doesn’t have the smell of death — we’ve been hiring reporters. I can’t look ahead; it would be foolish to speculate about where things are headed. I just don’t see newspapers going away anytime soon.

Is there anything else you want to discuss?

Memoirs, I want to talk about memoir — it’s such a popular and problematic medium now. As I wrote my own book, I read a lot of memoirs to find out how people dealt with quotations, things like that, and my favorite was Memories of a Catholic Girlhood by Mary McCarthy, a memoir from, I guess, it’s the ’50s. At the end of each chapter, she has a version of the story told by others; it’s a sort of reality check after each section, and a brilliant thing to do. Memoirs started becoming more and more popular around the time of Angela’s Ashes, and they also became more and more depressing and dire. Around that time, if you weren’t an alcoholic or an addict, well, then you didn’t have a story to tell. Lately, though, memoirs have become more about stories of everyday life, and that’s what journalists are interested in. So, I see good things for memoir.

As I read the book, I would get clear pictures of people in it; and when I re-read it, I thought, she has just one detail about this guy! But I could see him clearly. You have a fantastic eye for the telling detail, the one that sets up vibrations that outline the character.

But that’s memory. What you remember.

The detail that sticks.

Yes.

________________________________________________________

Related event:

Laurie Hertzel will read from her book, News to Me: Adventures of an Accidental Journalist on Monday, September 13, at 7:30 pm at Magers & Quinn Booksellers in Minneapolis.

Laurie Hertzel’s memoir, News to Me: Adventures of an Accidental Journalist, will be released by University of Minnesota Press in September 2010.

________________________________________________________

About the author: Ann Klefstad is an artist and writer in Duluth.