Master and Commander

Artist Ruben Nusz grapples with the "masterpieces" from the Louvre, now on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and with the slippery, troublesome nature of the term itself.

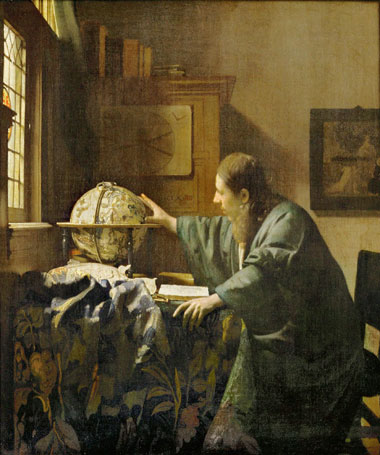

LET ME BEGIN BY SAYING THAT I ENJOYED The Louvre and the Masterpiece exhibition, now on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Filled with an assortment of jaw-dropping works of art, the show is dazzling, especially for fans of Johannes Vermeer, lost-wax cast sculpture, and archaic ceramics.

It’s also important to note that museum attendance is down across the country and that, now more than ever, institutions rely on blockbuster extravaganzas to lure in traffic, not to mention funding. The Louvre and the Masterpiece comes packaged with a show-stopping title and some well-known, big-name artists (Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Jean-Simeon Chardin). At the same time, the exhibition itself is subtler than its grand title suggests — more like a Giorgio Morandi still life painting than a Michelangelo — and the majority of the selections appear to be minor works, even fakes in some cases. With its thimble-sized sculptures, its thoughtfully curated array of pristine objets d’art, and its historic pedigree, the show will captivate any viewer or artist with an interest in art and art history.

Now allow me to start again, but more critically. If we home in on the titular theme of the show (the notion of “masterpiece,” specifically) we’re inevitably stuck with a muddled pile of gendered, outdated associations that make this term inapplicable in the modern art historical lexicon; that semantic murkiness taints, from the outset, an otherwise irresistible, if inconsistent, exhibition.

Originally, the term “masterpiece” simply described a work of art or craft “produced by an apprentice or a journeyman aspiring to become a master craftsman in the old European guild system.” This masterwork was assumed to represent a culmination of years of training in crafts like painting, goldsmithing, or knifemaking. In some respects, a “masterpiece” translates, by today’s standards, to an MFA thesis exhibition, but with a heavier emphasis on the acquisition of technical skill.

Over the years, the notion of “masterpiece” has evolved to imply something more profound, intended to represent an accomplished work that towers above all others in its embodiment of artistic aptitude; such a piece is deemed to be possibly the best work an artist has contributed to this world — a work of art that, by its definition, lies beyond comparison and largely above reproach.

Still, no matter its glibness or evaluative shortcomings, the designation “masterpiece” isn’t leaving us any time soon. And, for me, that isn’t even the most frustrating aspect of this exhibition. Frankly, it’s quite difficult for me to rave wholeheartedly about the show when not one work of art appears to have been made by a woman (I’m not counting the anonymous selections). Sure, these pieces are products of a bygone, deeply patriarchal past (the old European guild system, for example, refused women); under the circumstances, it might even be germane simply to view the show through the lens of history. Nevertheless, the lack of any acknowledgment, if not inclusion, of masterworks by women troubles me, especially when the conceit of the show covers the notion of “masterpiece” on a broad scale. Twenty-nine curators at the Louvre each contemplated the nature of the masterpiece and not one of them determined that it would be sensible to include, or at least give a nod to a couple of works by known female artists.

These qualms run against what is an otherwise stunning exhibition. But if we, for a moment, abandon these contextual concerns and simply consider a select few works on view in The Louvre and the Masterpiece, there is much insight to be gained.

______________________________________________________

So compelling are some of the pieces in this exhibition that, in spite of my misgivings, I yearn to believe in the “masterpiece” — that certain artworks really are transcendent achievements that might elevate us above nihilism, beyond banality.

______________________________________________________

Jean-Simeon Chardin’s Child with Top conveys a weightlessness missing in much of contemporary art; you feel like you want to kiss this painting of a little child. Modernist and postmodernist works sometimes stumble on their own self-conscious seriousness, and Chardin offers us a work of art as light and – arguably important — as an afternoon nap.

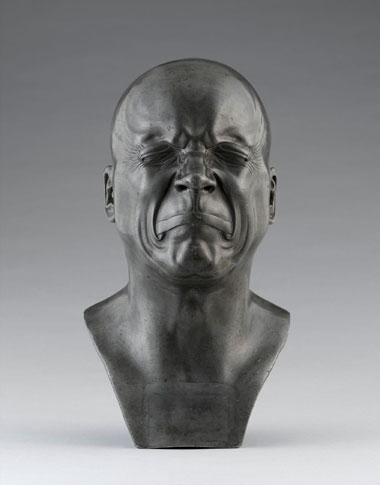

What’s more, Georges de la Tour, Johannes Vermeer, and John Martin all imbue their fantastic paintings with narrative depth. Also included in the show are some supremely well executed sculptures, including an expressive bust by Franz Xavier Messerschmidt.

Then there’s the Leonardo da Vinci Drapery Study, a gorgeous grisaille painting — as the title suggests, it’s just a study really — that he accomplished in his teens; even now it looks surprisingly contemporary — with echoes of Paul Cezanne, Larry Rivers, and Minnesota painter, Cherith Lundin. This work, in particular, should be essential viewing for any local student of art.

In fact, so compelling are Da Vinci’s study and other pieces in the exhibition that, in spite of my misgivings, I yearn to believe in the “masterpiece” — that certain artworks really are transcendent achievements that might elevate us above nihilism, beyond banality. Yet, as strange as it sounds, isn’t banality reality’s masterpiece? In the background, before the press preview of the MIA’s exhibition, a child’s laugh echoed through the hallway. Is that a masterpiece?

I’m going to sound like a Marxist when I say it, but perhaps life’s daily “masterpieces” are not considered such because they fail to elevate the upper classes above the common people. The masterpiece, as defined by the Louvre, is perhaps just a treasure of the rich, an emblem of fine taste and an “educated” aesthetic sensibility. But what of the daily masterpiece of love’s kiss?

Here’s an example of what I’m getting at: Many of these perfectly profound but everyday moments, like that captured in Chardin’s delicate painting of a child with his top, are celebrated in the breathtaking, nearly flawless film by Spike Jonze, Where the Wild Things Are. In an adaptation that stays true to the tone of Maurice Sendak’s 338-word source material (apparently, director Spike Jonze was handpicked by the author), the filmmaker and studio have created a work of art as expressive as The Wizard of Oz, as emotional as Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind, and as subtextually complex as an Ingmar Bergman film.

This film is so good it makes my stomach hurt to think about it — like communing with friends and family long gone — from the past, from the future. And this is actually why I continue to paint – this promise of connection, of communion. I want to have a conversation with Rembrandt; I want to confer with Joan Mitchell and see if she knows why it is we painters do this utterly superfluous thing we do. Francis Bacon put it best when he said that “the greatest art always returns you to the vulnerability of the human situation.”

Where the Wild things Are, with its Karen O score and pitch-perfect performances by actors Max Records and Catherine Keener, achieves this aim so well that, in a sense, it’s problematic to compare the film to the virtuosic, but rather emotionless assemblage of work in the MIA exhibition. I mean, after I saw Where the Wild Things Are, I was tempted to phone my mother. Does the fact that the film elicits such a strong, visceral response qualify it as a masterpiece?

I confess, I have no idea what the term means anymore.

So, maybe it would be wise to retire the word for now, given its nebulous, slippery definition. It’s enough simply to consider The Louvre and the Masterpiece a visually stunning, must-see collection of “special objects” — maybe not as ephemeral or as fulfilling as love, but certainly a true pleasure to look at, to converse with and about, to debate and, not least, to enjoy.

______________________________________________________

Noted exhibition details:

The Louvre and the Masterpiece will be on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through January 10, 2010.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Originally from South Dakota, Minnesota artist Ruben Nusz was raised by cowboys and later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota. In 2003 Nusz directed a feature-length documentary that toured the festival circuit. He has exhibited mixed-media works at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Rosalux Gallery, Umber Studios and the Hopkins Center for the Arts. He is one of the co-founders of SELLOUT Gallery, an artist-run space devoted to the exhibition of work by emerging and mid-career artists as well as independent curators.