10 Alt Comics Artists to Watch

Nate Patrin offers a cheatsheet on the genre-defying artists featured in this year's Autoptic festival of independent culture.

Compared to the emergence of underground comix in the ’70s and ’80s or the alt-comics boom of the ’80s and ’90s, this era’s wave of creators is significantly harder to pin down — generationally, culturally, stylistically, or otherwise. Generations cross over to influence the others’ sensibilities, and lines between high and low art are eroded in ways not even Lichtenstein or Crumb could have dreamed up. This era’s artists are just as likely to express their personal lives through hybridized takes on manga, sci-fi, or anthropomorphic art as they are in more traditional verite forms. The community, as a whole, can no longer settle for the comfortable complacency of the straight-white-dude voice being a reliable default perspective. In other words, comics have never felt less earthbound, constrained, or predictable — and in the independent scene, the “It” in “Do It Yourself” has never felt more open-ended.

For the second time in three years, the Minneapolis-based Autoptic festival has arrived to give both local and international comic artists and illustrators a chance to show and discuss their work in this fluid context. As an exhibition, it’s wide-open — while traditional superhero and other genre-action creators might have less of a presence than at your typical mainstream con, everything from Carl Barks-caliber, all-ages adventure to phantasmagoric body-horror art-comics are there for the perusing (and purchasing).

But in its newly expanded two-day stretch, Autoptic also doubles as a forum where special guests from many scenes can share their experiences with fans and fellow artists alike. This year’s lineup of featured artists includes a wide range of creators who have something unique to contribute from their individual perspectives. Here’s why each of them is worth checking out.

Josh Bayer

Since emerging in the late ’80s, Bayer has grown into a jack of all trades — illustrator, comic artist, editor, publisher, and teacher — while still finding a way to master them all. Vivid when working in scratchy, splattery brush-and-ink or visceral, seething watercolors, Bayer’s work is not just the culmination of visual precedents from the old-school alt and cape-comics worlds, it’s a mutation into a normalized grotesque. Building off the frenetic punk energy of Raymond Pettibon and Gary Panter for comics like Raw Power, taking Jack Kirby’s heroic sci-fi weirdness to fever-dream ends in Mister Incompleto, overseeing a cavalcade of deconstructions of newspaper-strip icons for the multi-artist Suspect Device anthology series — every corner of comics is grist for his pen.

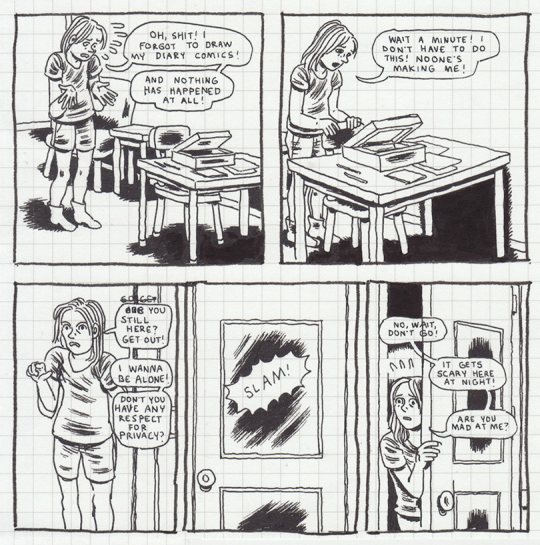

Gabrielle Bell

It only makes sense that Gabrielle Bell’s comics have a “lived-in” feel, and it’s her dedication to autobio storytelling that benefits the most from her subdued yet expressive style. Her ongoing series Lucky depicts her careening through a day-to-day artist’s life with a stoic mix of bewilderment and self-conscious humor (one piece has her regard a “drunk Polish guy in [a] Darth Vader mask scaring people at two on a Sunday afternoon… he accomplished more that morning than I had all weekend”). While her line looks freewheeling and spontaneous, it’s nevertheless still powerfully composed, filled with the kind of you-are-there touches that make even her most mundane moments feel wholly alive.

Charles Burns

It’s impossible to overstate both how arresting and how versatile Charles Burns’s work has been over the decades. His immediately recognizable sensibility — surrealist horror-noir a’la Davids Lynch and Cronenberg, filtered through EC Comics — has graced everything from Iggy Pop records to OK Soda cans to the cover of The Believer. Emerging at the center of ’80s alt-culture mainstays like RAW and the Subterranean Pop fanzine, Burns’s work became mainstreamed and made essential thanks to the sort of highly refined, eye-popping craft — few comic artists have done more with high-contrast black-and-white — that made 2005’s Black Hole one of the most striking serial comics of the past 25 years. Burns’s latest works, a trilogy comprised of X’ed Out, The Hive, and Sugar Skull, continue to reveal him to be a creator able to deal in both the oddly fantastical and the all-too-human, often in unsettling parallel.

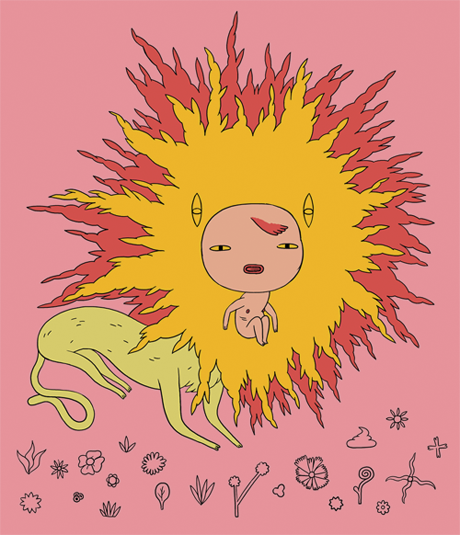

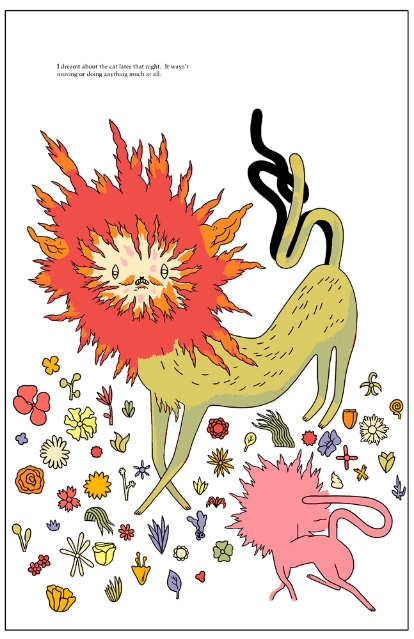

Michael DeForge

Having established himself as one of the most influential yet impossible-to-duplicate comic artists of this decade, DeForge sits squarely in the thick of contemporary pop culture (his visual imprint is all over the beloved Cartoon Network animated series, Adventure Time) while still presenting a staggeringly imaginative take on pop-art abstraction. It’s not just that his work vibrates off the page and nails you right in the forebrain: his surreal illustrations are coupled with the kind of sharp storytelling that gives even his queasiest visuals something to connect to. Whether it’s recasting Prince as an extraterrestrial being (Leather Space Man), fashionably detailing the beautiful, grotesque lives of his home country’s fictional monarchs (Canadian Royalty), or detailing the aftereffects of dealing with mental illness (First Year Healthy), even his most outlandish work is grounded in the familiar, which only makes it that much more haunting.

Ines Estrada

A resident of Mexico City, Estrada has instilled her self-published zines and comics with a modern sense of psychedelic underground comix style that fits solidly in the best parts of DIY tradition. (Including, naturally, her tips on how, exactly, to Do It Yourself.) Drawing off a rich history of local and regional visual storytelling tropes and the culture of her home city, Estrada’s stories of funny-animal stoners (Pachecomics), tripping dimension-hoppers (Lapsos), and close-quarters apartment-dwellers (Sindicalismo 89) are standout works, but they’re also just the immediately-eye-catching surface of an even deeper commitment to comics. Her online shop, Gatosaurio, reveals an entrepreneurial spirit that helps keep her work prominent and accessible in the Mexico City comics scene she’s worked hard to help build, including through the Gang Bang Bong anthology series she co-edits.

Edie Fake

With a focus on trans self-awareness, queer culture, and the feeling of coming to terms with one’s own body, Edie Fake’s work — in comics and performance art alike — is a vital and crucial contribution to the artistic conversation around contemporary LGBT issues of identity. But his fine-lined, monochrome illustrations that blur chaos and precision aren’t simple, cut-and-dry statements. In works like his recurring Gaylord Phoenix comic, you get a sense of disorienting intimacy, reconciling the physical and the emotional in the process of realizing how such things pull at you from inside and out. In Fake’s worlds, nobody wants to hide, and nobody has to, in this process of self-discovery. There’s still a sly, absurd sense of humor in his work — check out his anthology zine, Lil’ Buddies, which collects the inadvertently bizarre iconography of anthropomorphized product mascots, or Memory Palaces and its colorful reimaginings of defunct queer clubs and theaters of the Chicago area.

Sammy Harkham

Whatever barrier it is that usually separates cartoon iconography from queasy, unnerving dread, Sammy Harkham clearly enjoys working without it. Goofy and visceral in equal measure, his serial anthology, Crickets, draws out stories of stark horror, ennui, and desperation in a deceptively whimsical style that underscores the ironies of simple comics language. (The Black Death stories in Crickets are filled with what looks deceptively like deadpan slapstick until it actually registers that the arrow-filled protagonist and his golem companion are going through actual torment.) Strong as it is, his own work is arguably overshadowed by his role as the editor of the Kramers Ergot series, which began life as a 48-page minicomic in 2000 and, within three years, had become one of the most prestigious alt-comics anthologies in the world.

Aidan Koch

Calling Aidan Koch a fine artist or a comic artist seems insufficient; her work seems to manifest most clearly as an associative collection of images that allude to narratives rather than simply lay them out for you. Impressionistic pencil hatching and wayward smudges of charcoal and graphite turn straightforward portraits and silhouettes into something more ghostly and elusive; negative space consumes free-floating fragments of physicality and vision, and loose, unmoored flashes of vision aimed towards receding landscapes hint at an emotional tumult that distorts and obscures each observation. Her work, Blue Period, a brief but riveting meditation on depression, gained her entry into 2014’s edition of Best American Comics.

Laura Park

Park’s watercolor-rich illustrations seem tailor-made for acclaim-worthy autobio comics and lighthearted spot illustrations — which is why it’s so impressive that her work focuses on the many ways she can turn those standards in on themselves. Her line is lively, expressive, and simultaneously capable of cheery silliness and emotional gut-punches; the same visual sensibility she uses to portray games of peek-a-boo with her French bulldog or Thanksgiving dinners can be striking in a completely different way when she recounts racist humiliation or being anxious over a medical condition. Her colorful palette, enthusiasm for typographical flourishes, and rendering of personal experience in fantastical ways put her in a class somewhere between Lynda Barry and Dustin Harbin. Her work is too resonant to be twee, too spirited to be morbid.

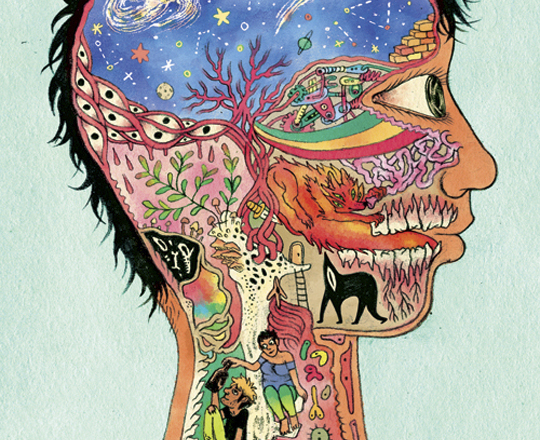

Jillian Tamaki

The Calgary-born Tamaki has earned recent acclaim and enthusiasm for her Ignatz Award-winning, NYT-bestselling Supermutant Magic Academy (Drawn & Quarterly), a goofy and touching twist on YA fantasy tropes where teenage hormones, philosophical angst, and self-discovery play out in a Hogwarts-meets-Xavier Institute school. But that comic’s just one culmination of her long-building talents, which she’s developed to give deep character studies and one-off gags alike a subtly dark absurdism. (One evergreen short, “Have a Sexy Little Halloween”, takes off from the cliche booty-shorts-and-crop-top versions of women’s Halloween costumes to create outfits like “Sexy Hungry-Man Dinner” and “Sexy Inexplicable Melancholy”.) Stylistically, her work is full of evocative, realistic touches, whether meticulously detailed or deceptively simple, and she excels when juxtaposing everyday concerns and emotions with a certain magical-realism strangeness made comfortable.

Related event information: The Autoptic festival runs August 8 and 9, 2015 at ARIA in downtown Minneapolis. Find more: http://autoptic.org/.