Wrestling with Merce

Lightsey Darst offers a first-person appraisal of Merce Cunningham's work - in performance, as a legacy, as danced movement, as fodder for fellow feeling (or not) - framed around recent shows at the Walker paying tribute to the storied choreographer.

I overheard a conversation on Merce Cunningham the other day. It went something like this: “great innovator. . . Merce Cunningham [said with reverence]. . . don’t really enjoy it. . . appreciate. . . appreciate. . . chance. . . Cunningham [said with reverence]. . . unitard. . . well, that was art!”

It made me laugh, but it also hit a little close to home. I know the critical line on Cunningham, I can recite the innovations, but the dance itself I’ve struggled with. The reverence in which Cunningham is held doesn’t help. I don’t want to appreciate the dance (appreciation bores me, and, honestly, I don’t quite believe in it), I want to feel it. What, after all, is the point of being able to say that I saw the Merce Cunningham Dance Company if I can’t do more than recite the Wikipedia entry?

This is not about whether I know what Cunningham was after, mind; it’s not about process, and it’s not about Cunningham’s choreographic skill. It’s about my nervous system and my heart (yes I did say the h-word): can I tune my animal and emotional self in to this work?

First, what’s the problem?

Before this weekend’s performance, I’d seen the company once in person, at 2008’s Rainbow Quarry Ocean performance, and found myself caught up in the design, excited at certain moments, and yes, appreciating the whole, but effortfully, consciously. But the movement kept me mostly in the cold — severely heroic stuff, one-footed landings and endless balances, without any flourish of success, any prettiness or luxury. When I watch dance, I want to feel myself with the dancers, doing those gestures and feeling what they release in me; the experience is so different when (as James Sewell put it in a conversation) I don’t want to do what the dancers are doing.

I was thinking about this recently when I went to see Jérôme Bel’s charming Cédric Andrieux, at the Walker the weekend before MCDC; it is one of a series of pieces in which a single dancer relates his or her own life, with excerpts from dances which have been significant to him or her. The series lifts the curtain on the dancer’s hidden world. Cédric Andrieux danced with Cunningham for eight years, and I can’t imagine what sort of person would want to do that dance — so I’m curious.

Andrieux, to begin with, talks about his impression of the work beforehand — “abstract, cerebral, even boring” — and then his experience seeing the Cunningham company perform. He describes looking around, watching the audience as well as the performance, and feeling that, with Cunningham’s plotless and chance-driven work, “there were no more rules to watch a performance,” which felt “supergood.”

Lovely, but I’ve heard this before, even written it myself.

What comes next is more interesting. Andrieux describes working with Cunningham. Class began with a prescribed set of exercises, the same every day; Andrieux suspected that Cunningham saw this as zen, but he says he found it “totally depressing”. Watching Andrieux reenact it, I too am depressed: the class he depicts seems more exercise than dance.

Andrieux goes on to describe the rehearsal process. Cunningham created movement using his custom computer program, then applied it to live dancers as if they were automatons, instructing them step by step, first legs, then torso, then arms, without any sense of phrase, without interpretation, and of course without music to carry any of it along. As if that weren’t scary enough for a dancer, the movements themselves are fiendishly difficult. “I can almost never do exactly what he asks of me,” Andrieux says — this beautifully trained dancer — and so “I feel like shit.”

But the performance, he says, was ecstatic: a flight of pure physical exertion, an altered state. “I dance and I see what happens,” Andrieux says. “I am totally in the moment,” a feeling that “fulfills me and liberates me.” Cunningham, standing in the wings night after night, never said much about the performance afterward. Andrieux came to understand that “failure wasn’t that important to him,” that he liked the awkwardness of the outer reaches of his dancers’ ability, he liked the moments of near-miss.

When I see those moments, though, I mostly feel uncomfortable. Cunningham doesn’t traffic in the obvious attempts and collisions of contemporary modern dance; to the average viewer, the Cunningham edge may be mostly visible as strain.

As for the excerpted dances, I can’t make much of a short excerpt from Biped, except to note its extraordinary difficulty. Suite for 5 (an earlier work) does more for me. My mind does wander, as promised, but then Andrieux faces front, extends his hand with thumb and forefinger stretched apart, as if he were measuring my face from a distance, and I twitch.

I don’t want to make too much of this twitch, but I think it’s more than muscular tension releasing. It comes from the nervous system, so I can’t call it the result of emotion; rather, it precedes an emotion, more like a moment of recognition. But what I recognize, or what it has to do with the motions before and after, I don’t know.

I love Jennifer Hart’s insight: “His work is less manipulative than other choreography. It’s not demanding that you feel one way or another like some that says ‘this dance was made to make you feel sad’ or ‘this dance should make you happy.’ Cunningham works against that”

I ASK FOR HELP: HOW DO YOU RELATE TO CUNNINGHAM?

People have all kinds of responses. Many confess. “I know this is heresy,” one says, “but I don’t like Cunningham.” Another: “Does anyone ‘like’ Duchamp readymades?” Several say they “appreciate” it, but don’t care for the aesthetic.

Others seem a little angry the question is even being asked. Meet Cunningham on his ground, they seem to say, and you’ll find more than enough there. I wonder: Is my desire to feel the dance weak, a personal shortcoming, like reading a novel and wishing I were the main character? Maybe in a strict sense it is, but I have plenty of company. “I blame myself,” James Sewell said, but then admitted feeling the same lack of response, the same longing for an emotional connection that doesn’t occur.

Like many choreographers, Megan Mayer indicated appreciation for the freedom Cunningham brought to dance, but she also reflected on his work’s effect: “I am blown away by his expansion of how the body could move. His articulation of the torso by adding twists and curves expanded my idea of modern dance. When I watch his movement I see different planes and geometric angles than I see in other styles. It makes me think of light refraction, of splintering trees, and of being up in an airplane when the sun is streaming through the cabin from a small window.” Emotional response, she suggests, can go beyond the directly emotional.

Chris Fischbach also questioned the division between emotion and intellect. “I am not sure there is a difference between a visceral emotional response and an intellectual delight at understanding or revelation. Likewise, one can feel delight at confusion and that delight might be identical in synapse-firing as an ’emotional response.’ “

I loved Jennifer Hart‘s insight: “I think you could make an argument that his work is less manipulative than other choreography. It’s not demanding that you feel one way or another. There is some choreography that says ‘this dance was made to make you feel sad’ or ‘this dance should make you happy.’ Cunningham works against that. It’s more like how you might look at nature. Maybe there’s a big live oak in front of you. It’s got all sorts of craggy limbs. Some may look at that tree and cry over its beauty. Some may think it’s ugly. I can be moved by his dances but it seems to relate to circumstances or being in the right place at the right time.”

Jamey Garner connects Cunningham’s famous process to a potential emotional response: “I was just remembering Cunningham’s use of the I Ching tonight. The use of chance. The ability to give up the intellect to intuition. For me, Cunningham was more than intellect only. He embraced chance and intuition.”

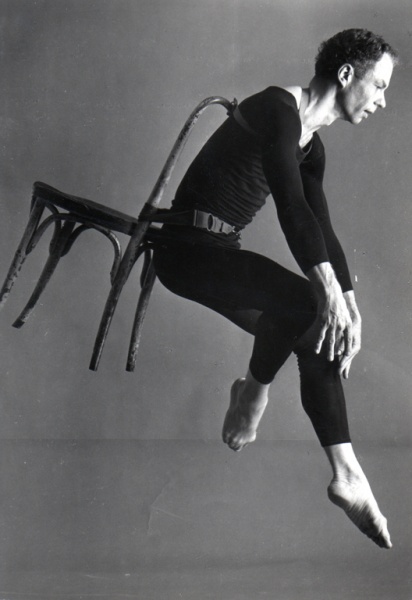

That man was a fantastic dancer once: at ease in air, one of the lucky few with all the time in the world to come down. I’ve been told that he felt the loss of that amazing jump keenly — no wonder. Could the later, especially arduous dances be Cunningham’s sonnets to his own body?

WELL THEN. It’s the evening of the Farewell Legacy Tour performance at the Walker, and though I’m now armed with the help above, I’m apprehensive. Will I feel? And if I don’t, have I somehow failed? Is it a failure even to ask the question?

Even before the curtain goes up on 1998’s Pond Way, I can hear heavy landings behind the curtain, evidence of herculean effort, and I can’t help wincing in sympathy. When the curtain does go up, I’m transfixed by the beautiful costumes (the work of Suzanne Gallo) and the lovely dancers; at first all is twitchy and small, like pond water under a microscope. But then the heroic moves commence: muscle-shredding multipart jumps, sustained balances. Throughout the concert, I wonder at the straining forms of the dancers, who are (to judge by their bios) mostly young; I wonder how long they could do this, and how their knees will creak later. I feel myself in pain for them and wonder why we’re burning them on stage this way, why the most beautiful torso in the world is panting before me, exhausted.

What is it I’m seeing? Young people spending themselves for a dead man’s work. That man was a fantastic dancer once, as the photographs attest: at ease in air, one of the lucky few with all the time in the world to come down. I’ve been told that Cunningham felt the loss of that amazing jump keenly — no wonder. As the concert goes on and we go backward through repertory, first to 1968’s RainForest, then to 1958’s Antic Meet, I see less and less of that brittle exertion I think of as Cunningham’s style, less force, more pleasure and play; suddenly I’m thinking of Shakespeare’s sonnets, how he promised that invisible beloved, “As [time] takes from you, I engraft you new,” and how he lied, because all we read is his own jealous adoration. Could the later dances, the ones created in the arduous fashion Andrieux describes, be Cunningham’s sonnets to his own body? It’s an unauthorized thought, shamefully biographical and sure to shock the faithful. But it gives me a way in. Thinking of Cunningham standing in the wings watching the strain he once felt, I’m moved.

And then I think that these are the last few chances to see this surrogate body he made, and I’m still more moved. He knew what he was doing when he planned this last year for the company; I think he knew that in his absence the dance could only become more and more brittle.

But to some degree this is ego on my part, the good student making her thesis. Mostly, everyone was right: you have to let this dance be itself. Your mind wanders, and then you seize on some moment, some slant of light or sudden exaltation that reminds you of something else. You make up stories; you get distracted by the sets; you think about what you want to feel when you get up again. Nothing is needed and nothing is forbidden. This open field feels, sometimes, frustrating and tiresome, and other times, when my response is especially creative, it feels, as Cédric Andrieux says, supergood.

I had one more surprise at the concert: the curtain. Because Cunningham’s dances are non-narrative, nothing in the dance signals the end. Instead, the curtain’s fall registers in my peripheral vision first as motion — another part of the dance, suddenly aerial. Then I realize what it means: the incipient end. A window into a world of fierce effort is closing. Suddenly everything is precious.

Noted and related event details:

Jérôme Bel’s Cédric Andrieux, written and performed by Andrieux and directed by Bel, was at the Walker’s McGuire Theater October 28 & 29; Merce Cunningham Dance Company performed the Farewell Legacy Tour performance there November 4.

The exhibition, Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham /Robert Rauschenberg is on view in the Walker galleries through April 8, 2012. All are part of the center’s extensive The Next Stage: Merce Cunningham at the Walker Art Center programming.