An Exquisite Preeminence of the Body

In the Walker's expansive exhibition, "Merce Cunningham: Common Time," artistic disciplines effortlessly traverse conventional boundaries, in much the same ways the influential choreographer did with his many collaborative partners.

When does a ragged leotard become a work of art? A silver mylar balloon? An inflated plastic box? A freestanding industrial floor fan? When they were created or re-contextualized by visual artists Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns and Bruce Nauman, respectively. Moreover, they become works of art as a costume or an element of décor created independently of, but for the sake of one of Merce Cunningham’s dances. Finally, they are elevated as such when they’re included as elements of the Walker Art Center’s celebration of the choreographer and his artistic collaborators, an exhibition titled Merce Cunningham: Common Time, on view in all seven galleries of the museum’s original Barnes building, through July 30.

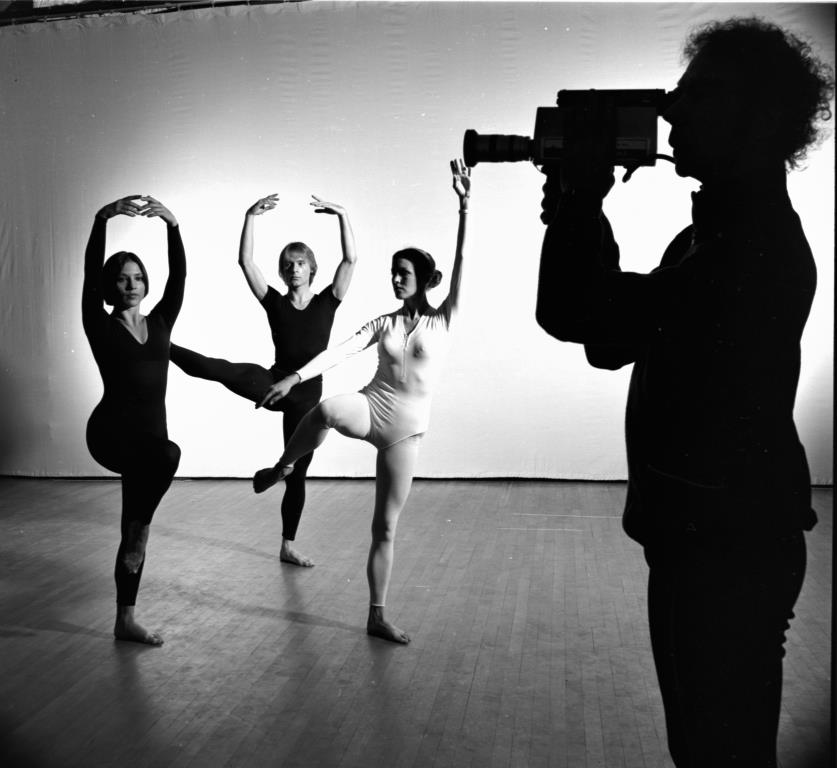

During its 50+ year history with Cunningham, the Walker has hosted exhibitions focused on the choreographer’s work and his chance-oriented collaborations with iconic composers/musicians, visual artists, and costume designers: In Art Performs Life, with Cunningham sharing the stage with Meredith Monk and Bill T. Jones; and in the series Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham/Robert Rauschenberg, Dance Works II: Merce Cunningham/Ernesto Neto, and Dance Works III: Merce Cunningham/Rei Kawakubo. Of course, the Walker has long been a patron of Cunningham and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company as well, culminating in the presentation of the often-called monumental Ocean on the floor of a quarry in Waite Park, MN, which was shot and subsequently turned into a film by another Cunningham collaborator, Charles Atlas.

But after Cunningham passed in 2009, the Walker acquired the choreographer’s entire archive: photographs, scores, costumes, sets, posters, props, décor, videos, and more items accumulated during Cunningham’s prodigious career. More than 4,000 objects from the Cunningham Dance Foundation are now in the Walker’s archive. And more than 60 of them on are view in Merce Cunningham: Common Time. These include an array of leotards and costumes in a variety of fabrics (wool? fur? How hot that must have been!), which might be exhibited adjacent to archival video of Cunningham and his main muse, Carolyn Brown, performing in that garb, or arrayed in a rainbow of hues (for the piece Second Hand) mimicking the color spectrum from violet to red created when the dancers lined up for their bows.

Warhol’s silver balloons? They were made for Rainforest and occupy their own room, where fans keep them aloft and visitors are invited to play. In the next gallery are Johns’s plastic boxes for Walkaround Time, (also previously exhibited at the Walker in its One Work series), which he painted and drew on in homage to Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even aka “The Large Glass.” (Duchamp was also a pal of Cunningham and his partner, composer John Cage.) The fans, loud and blowing down dead-end corridors beside a spare, stage-like set? Those are a bit from Nauman’s original décor for Tread, which included 10 such fans blowing onto the audience.

In this expansive exhibition, artistic disciplines effortlessly traverse conventional boundaries, just as Cunningham and his collaborators did. (The activity during this celebration is likewise not limited to the Walker Art Center’s galleries, which during the opening included daily performances by eight dancers in a work called Staging by Maria Hassabi, most notably on a raspberry-pink carpet. There are also Cunningham-like Events, performed by four former Cunningham dancers, in the galleries, and Cunningham-related performances at Northrop and the Cowles Center.) The Walker exhibition also includes rooms focusing on the sound scores and musical innovations of Cage, David Tudor, and other composers with whom the choreographer worked.

There are artful sketches of costume designs and a sculpture by Isamu Noguchi (a collaborator of Martha Graham’s, with whom Cunningham danced early in his career). There are vitrines with programs, sheet music, and Cage’s I Ching or Book of Changes. One gallery was “converted” into Cage and Cunningham’s Westbeth studio, replete with Warhol’s film Empire showing on one wall (the studio had views of the building). Another is a panopticon-like gallery of screens—Charles Atlas’ piece MC9, which immerses the visitor into a time machine of Cunningham dances at various times of life, in various places.

The quiet center of all of this activity is the body: Cunningham’s body, foremost, which gave rise to a choreographic aesthetic, methodology, and style that the choreographer paired—as an entity separate from and equal to any other discipline—with music, costumes, lighting, and décor.

Mark Lancaster’s sumptuous gold velour drapery for Sounddance, which CCN-Ballet de Lorraine recently performed at Northrop along with Fabrications, is on view. Elsewhere are notes from Cunningham on choreography with “spastic leaps + turn,” video of Cage drinking champagne and smoking while performing, several of Cunningham’s whimsical insect drawings. Life wasn’t always happening on stage or in the studio. Integral to making dances, obviously, was a great sense of fun.

The quiet center of all of this activity is the body: Cunningham’s body, foremost, which gave rise to a choreographic aesthetic, methodology, and style that the choreographer paired—as an entity separate from and equal to any other discipline—with music, costumes, lighting, and décor. All which would occupy the same space in the moments they came together, which Cunningham called “common time.”

Engaging in this exhibition also requires (or at least invites) the visitor to participate, to experience a sense of Cunningham’s common time, using their body and all their faculties. Hold, push, fling, gently kick those mylar balloons around; or, simply observe how they tend to escape their designated room. Sandwich yourself in between the high close walls of Nauman’s Green Light Corridor (Selfie Central in this exhibition). Walk beneath the white square opening of Robert Morris’s Portal. Encounter multiple Merces and myriad Cunningham dancers while wandering among the screens of Atlas’s MC9. Listen, look, feel. The exhibition is a sensory, kinetic experience.

Cunningham’s kinetic body was the template on which he initially created his singular style of movement—often by disassembling his physiology into units, then tossing dice or the I Ching to determine in which direction the arm or leg would go, or which the shape the torso would make, then combining all of those perilous twists, extensions, curves, and hops into a breathtaking whole. This was taught to several generations of dancers, many of whom went on to create their own singular choreographic approaches and work.

Watching his dancers on the various screens throughout the exhibition, however, brings the fundamental, exquisite preeminence of the body in Cunningham’s work to the fore. Despite the excruciating detail and difficulty of the choreography, the dancers are supremely self-assured, without affectation or pretense. Their bodies, stripped of all identifying inflection, are whip-smart, lean, forthright; their movements clean, with the clarity of exactitude; their effort is imperceptible. They are modern in the purest sense.

Merce Cunningham: Common Time takes as its thesis the late choreographer and dancer’s influence on mainly the post-war visual artists, composers, and costume/set designers with whom Cunningham collaborated. In doing so, the exhibition brings Cunningham out of the dance “ghetto,” out of the calibration of disciplines that puts dance—and modern dance, in particular—on the lowest rung for resources including funding, coverage, education, critical appreciation, and understanding.

But the exhibition also raises a vexing question: Who has this kind of influence today? Who has the ego-less panache, the curiosity and knowledge of other artistic innovators, the connections, and the rigor and vigor to pursue an aesthetic orientation to multidisciplinary collaboration at the level that Cunningham did? Who now does so with the ability, as this exhibition argues, to change not only artistic process and practice but to alter and fundamentally influence the course of art history? While keeping dance—the neuroscience mystery connecting body and brain, the most ephemeral of art forms created with the finite interactions of nerve, muscle and bone—as the instigator? We may never know.

Noted exhibition details: Merce Cunningham: Common Time is on view at the Walker Art Center from February 8 through July 30, 2017. Find additional information about related performances and events on the Walker’s website.