Working in a Forgotten Technology

Nate Patrin talks with artist Ian Babineau about the techno-industrial aesthetics and old school craft of his risographs, remixing his drawings and paintings on 1980s printing tech to create distinctively trippy mixed-media zines and prints.

introductionThe risograph is a relatively recent development in the field of small-scale printing, and it emerged at a particular moment in history: a popular short-run press option in the late ’80s, it was one of the last new print technologies to be standardized before the internet took off. Since then, what was once a machine prized for its utility and efficiency has found new life as a facilitator of independent art projects and zines, as the endlessly mutable options the Riso offers can provide a unique aesthetic and workflow that proves artistic spontaneity and techno-industrial production aren’t mutually exclusive. St. Paul Riso artist Ian Babineau creates posters, zines, and art prints from a small apartment bedroom, which I visited to get a look at the process and for insight into how he takes advantage of his medium’s unique traits.

Nate patrinHow did your artistic influences develop?

ian BabineauI’m influenced by a lot of different types of artists, not just visual artists. Starting visually or aesthetically, when I was in grade school and painting, then middle school and high school, I was obsessed with Van Gogh… as corny as that answer may be.

NPThere could be a connection between impressionism and what you do with your work.

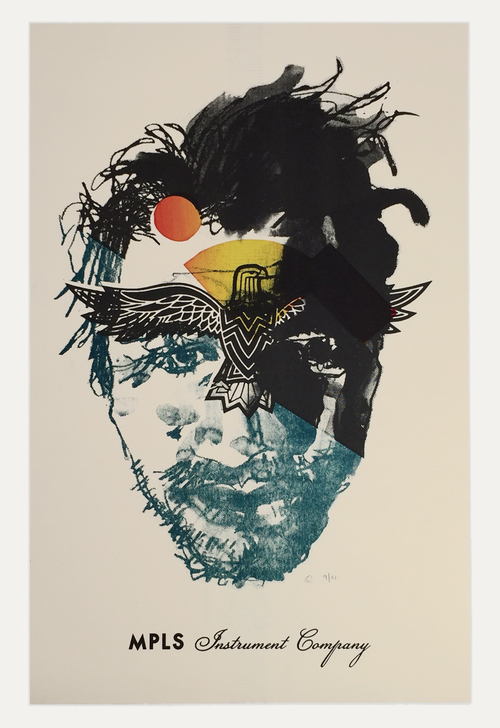

IBWhat I liked about Van Gogh was how loose his color choice was for his time, and how expressive the brushwork is. I gravitated towards that as I was learning how to be a painter, but at a very young age — I never actually formally studied art, as far as pursuing it at a university or something like that. But in recent years I’ve been hugely influenced by a printing studio that I learned about in the Schoolhaus program, a duo from Chicago called Sonnenzimmer. They really bridged the gap between fine art and print commercial art. They mix media with screenprinting and painting, and they do really cool large-scale installations; they even have an audio component to a lot of their exhibits. It’s very abstract. And I think that’s why I gravitate towards them: there’s less of a defined subject than you’d see in, maybe, a comic artist or typical screenprinter who’s making gig posters. Though I like those, too — in fact, Sonnenzimmer makes gig posters, but they approach it from a more abstract angle.

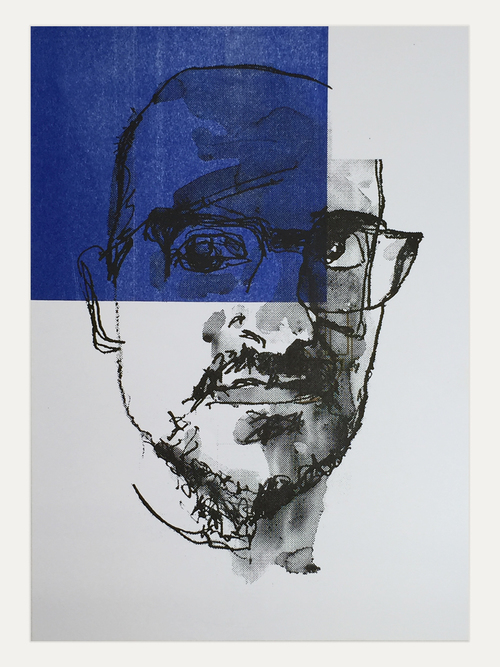

When I’m drawing or painting or making a line, I feel like I’m finding that flow, that way of being in the moment. What that means to me is that I’ve made a general decision to put my hand to the paper, but I don’t necessarily know really why I’ve made a certain mark. I’ll plan my general subject, but I really like there to be unplanned pieces to the work, especially when I’m drawing portraits. I experience this a lot, even in my sketchbook, sometimes the quickest, most reactive, in-the-moment line I make is the most definitive feature I see in the drawing. You have to keep that almost as a motor skill. It’s not always going to just be there — I have to sketch every day to get to the point where I feel like I can just skip the thought process, have a perception of somebody and just channel that, in the moment, through my mark.

I’m very much inspired by musicians. I like to listen to music while I’m creating art; I think that defines a lot of decisions I make when I’m painting or drawing. I almost see an aesthetic about somebody’s music — I really like psychedelic music. There’s an artist who really resonates: Nicolas Jaar, and his project Darkside is one that I really like. Or Tim Hecker, or Rafael Anton Irisarri… That kind of music where it almost feels like it’s floating in this in-between realm of physical reality and perceived emotional reality. If I can achieve an aesthetic in my visual art the way they achieve it in a listening experience for somebody, that’s a success to me. I can probably name more more musicians that I’m influenced by than I can visual artists — but music isn’t the way I want to channel that inspiration.

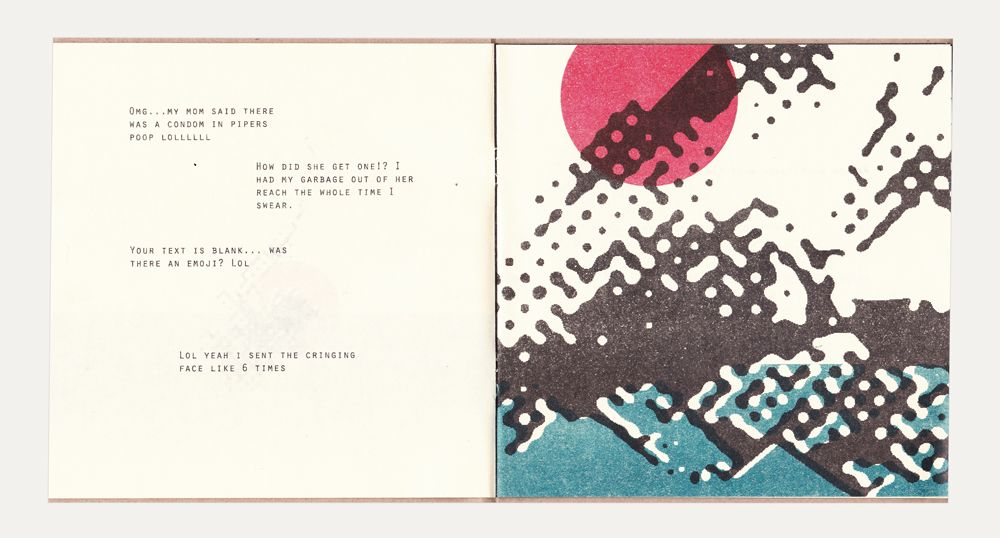

As an overall influence in my work, I really am fascinated by how much technology affects humans in today’s world, just thinking about where that might go. A lot of my art depicts this internal conflict I’m always feeling, every minute of the day, between what my identity is as a human and what it actually is because of the internet — how I form relationships, how meaningful those relationships actually are to me. Sometimes I feel like it’s almost impossible to form a meaningful relationship in today’s world; it’s different, at least.

NPThere used to be clear divisions — strangers, acquaintances, and people you know. Now there are so many gray areas between all those spaces.

IBYeah, you could have an acquaintance or a relationship solely on the internet, and that seems overly complicated to me. I mean, seemingly straightforward human emotions and interactions are over-complicated by things that look, at first, so simple, like a text message.

npSwitching gears: tell me a little about your Risograph machine.

IBThis model [Riso GR-3750] is probably one of the most popular models, built in the ’80s in Japan. They make current models right now, but those are really expensive and not a lot of artists can afford them. I know of about three artists that are actually operating a Risograph in the Twin Cities, but there are actually a lot of us all over the world.

npAre these machines hard to come by?

IBYes and no. They’re found mainly in churches, and in the Midwest we have a lot of Lutheran churches that just have them sitting around. I got mine on eBay — I found it, not at a church, but in Moorhead. And I actually got really lucky because this guy was the original owner. He had all the info on it — I think he bought it in the early ’90s and paid $20,000 for it. I purchased it from him for $300. This model generally goes for, depending on the condition, $2000-$3000 on eBay. So $300 was a steal, partly because he was up in Moorhead, so the shipping costs would be astronomical unless you were willing to drive up there, which is what we did.

npWhat first led you to the Risograph as a printing option?

IBIt’s definitely, the way I see it, a kind of a forgotten technology. The machine itself has this display, an ’80s kind of digital look, like the first Game Boy or the TI-80 calculator. Comic artists and some print artists, in particular, have started coming back to the Riso because of the aesthetic it provides. I was led to it by way of a design shop, called Aesthetic Apparatus, that uses it.

Worldwide, there’s probably 15 [ink-drum] colors total that you can use on this machine. So you have to get really creative about how you layer and mix colors. I only have seven colors, but I was able to find my favorite ones for the machine. A laser printer or an offset press does four-color CMYK patterns, and you can also do that on this machine. But I generally use the Riso more like a screenprinter would use it, and block color out. I think that’s what’s special about this machine: when you have the final print you see those blocked colors and the textures.

npThis is like the industrial side of making art.

IBIt’s true. And I should mention that, just to get this machine going, I had to take the back off… we got it back here [from Moorhead] at 1 a.m., and [my roommate] Michael and I had to carry it up four flights of stairs; it was so heavy, we got stuck in the middle of the first flight. Our neighbor, the person living below us, heard us wrestling with it and came out to see what was going on. He went and woke another friend up, and in the end it took all four of us guys to get it up here to my apartment. Even then, it was a struggle.

I’m in my zone making art when I’m painting or drawing. And this [risograph] has been a way of designing paintings and drawings, taking them further, applying them to different things, mass producing them, and making them available to a wider audience. I’ve never really gotten into the whole gallery thing where I’m like, “OK, I have this one painting on a white wall and then I have another, and we’ll sit and look at them and talk about them.” Not that it’s bad, or that I wouldn’t do that one day, but I really like the accessibility print-making gives to artwork; I like the price point, how many you can make.

npWorking with the Riso, are you adjusting to the idea of doing work with this medium in mind as well as just getting an aesthetic down?

IBWhen I approach a project that I know will eventually be risographed, that completely defines how I’m going to approach the work; it influences the marks that I make and the content of the project. But I think, at least in the way I’m working right now, I like to get into a certain zone when I’m painting or drawing, and then I like to revisit the painting. For instance, with the zine I’ve just made [All On Earth], I actually zoomed way in after scanning in a portrait I drew and painted: I zoomed in on some halftones and found some shapes that I thought were interesting. That process is sort of like going back to your own work and sampling it. A lot of comic artists draw their frames and print them; and a lot of graphic artists, they’ll go to old magazines with really cool old images and type — it’s something I definitely do at times; I really like to find old typefaces. From what I see of graphic artists, they’re image-sampling as well. I just like to sample my own paintings, too.

Related links and information: Look for Ian Babineau’s new zine, All On Earth, and see more work on his website: www.ianbabineau.com.