What You Can’t See

Andrea Carlson delves into the layered storytelling and stagecraft of two installations recently on view at Philadelphia's Fabric Workshop and Museum, by artists Nate Young (Minneapolis) and Cynthia Hopkins (Brooklyn).

“He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.”

Friedrich Nietzsche’s Aphorism 146 in Beyond Good and Evil (translated)

The Unseen Evidence of Things Substantiated is an installation in two acts by Minnesota’s own Nate Young. The elevator doors open onto the third-floor gallery, as curtains might, to reveal an empty stage. Upon exiting the elevator one is met with a dark, seemingly empty gallery. The title wall announcing the exhibition is acutely lit, but there is little ambient light by which to navigate the space. A black wall is placed two-thirds down the length of the room, creating a visual barrier to a partitioned space. Beyond the wall, sounds of an excited soliloquy emanate. That is where the action is coming from, and the viewer is pulled towards it. I am apprehensive as I approach the wall, as if there were some unknown beast hiding in its shadows. Taking in the span of the room, my eyes have time to adjust to the darkness. Part of the brilliance of this exhibition is its design: one must walk towards the unknown and, in doing so, the object reveals itself… sort of. Young states that this installation creates, “an effect where the object actually recedes into space, becoming conscious of its own presence.” What could be more terrifying then approaching an object that is on its way to self-awareness?

In the gloom I can identify a curved staircase leading up to some platform — maybe a gallows, maybe a crow’s nest from a ship. It turns out that the object is a blacker-than-velvet pulpit, swallowing up ambient light like a black hole. Later, I learn that the surfaces of the wall and sculpture have been prepared with a black paint used by NASA for its light-absorbing properties. The blackness effectively negates the surface area of the pulpit, erasing it entirely against a similarly painted backdrop. The spoken recording from beyond the wall is now given context; or maybe, it’s just that the pulpit is easier to recognize in the context of the preaching. Either way, in the vocalization I can easily pick out the word “obfuscates;” it’s apt, as that is exactly what the wall is doing to the object.

The last time I approached art with this level of physical caution was when I encountered Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s Documenta (12th) piece, Phantom Truck (2007), making its North American premiere at The Power Plant in Toronto in 2011. Manglano-Ovalle’s truck similarly filled a dimly-lit room and was created from the weak descriptions of a mobile biological weapons lab put forth by then U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell when addressing the United Nations Security Council prior to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. The low-light display of Phantom Truck made it hard to distinguish in detail, hard to scrutinize or detect. A reversal of Young’s title, The Unseen Evidence of Things Substantiated, would be fitting to describe Phantom Truck. Like the Phantom Truck, Young’s pulpit defies visual scrutiny and renders observations faulty. (In an ironic twist, the very material used to hide the pulpit, a high light-absorption paint, is also applied to the inner walls of telescopes to make the stars and planets visible.)

Young’s second act, the installation’s second space, utilizes the sleight-of-hand technique, called a “Pepper’s Ghost,” to create a hologram of disembodied, white-gloved hands. A “Pepper’s Ghost” is created by controlling the audiences sight-lines and presenting images captured on a reflective surface. In Young’s iteration of the technique, the viewer looks in through a door. Hidden beyond this established perimeter, a subject (in this case, white-gloved hands), is brightly illuminated and then reflected onto a sheet of glass, angled just so to pick up the projected glare of the object. The effect of this transferred image is ghostly and semi-transparent. Young’s Pepper’s Ghost technique utilizes video to create the lighted act. Gestures of the gloves are paced and paired with sounds of a preacher delivering an artist statement, his cadence at first ecstatic and singing, then measured and cool. Young’s language is concise and often rhyming; the narrative describes an imagined but as yet unmade painting.

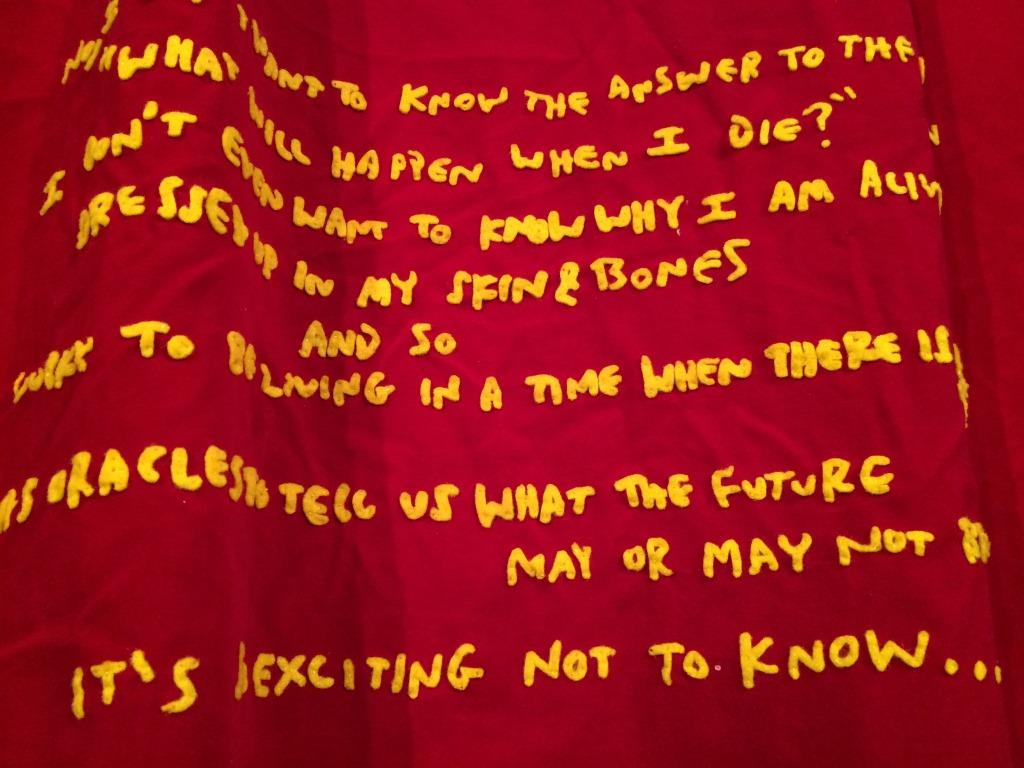

Young’s installation in light and shadow couldn’t be more different, in formal terms, from Cynthia Hopkins’ exhibition Memorabilia. But both artists’ works are thick in language, their respective galleries saturated with recordings of dramatic spoken narratives. At her core, Hopkins is a performer and storyteller, concerned about how the past and future may be shaped by the slivers understanding we share about what is happening now. In her work, even the eventual closing of this exhibition is anticipated in the various texts. The writings don’t take the form of jargon-laced artist statements; they are mellifluous, as if meant to be sung. Indeed, it is easy to imagine her texts as the basis for performance works. But the inclusion of writing also enforces a stillness and peace about the space. The following is transcribed from a wall in the installation, an example of how the artists’ words create an intimate and disarming gallery. In green, handwritten ink, the wall text reads, in part:

Okay so that was from the red quilt, and that was kind of saying to my Dad “hey Dad, you’re still alive! You got to fight to stay alive and you got to fight to create some record of your life, you know?” So now we’re going to move on to the next quilt, the quilt for This Clement World, which is the one with the astro turf, that’s to the right of the red one. And there is also a tribute kind of tribute show, theme, tribute theme, but in this case it’s a tribute to this clement world, the Earth as It is right now, and it’s kind of saying like hey I’m so, I’m so…” well it’s kind of doing what this requiem is doing and what this memorial event is doing which is to say is like celebrate. like lets celebrate that this that this show happened let’s celebrate that the Earth is here and say “thank you” it’s kind of like saying “hey, I’m so glad that you exist, I’m so grateful that you came into being, you know? That you were born.” It’s like saying “if I had a brass band, I’d set it on a mountain; and a symphony of horns would roll across the sea, then an orchestra of strings would join in from the rocky shore; and a choir of voices would rise up from deep down on the ocean floor singing: hallelujah hallelujah for the day that you were born! Hallelujah for the hundred years you’ve rolled across the ocean! And may you sail on the open water for a hundred more! “But truth be told, that song we just sang, rather than being a tribute to the Earth, on to a performance work, was a tribute to a boat, it was a birthday song to a boat that I was riding on at the time that I wrote it. And I was on that boat in the Arctic ocean with an organization called cape farewell[…]

The latter half of this wall text continues on, questioning the fate of humanity and the idea of an Anthropocene, or human-driven era, hell-bent on annihilation. But the viewer is reassured that even this dire space is a liminal one, as are all spaces, not reflective of any permanent state of being, but rather in a persistent state of flux. Hopkins continues the theme of transitional space, presenting her quilts as two-sided screens, each at once revealing the maker’s process while shrouding the work of the other side. Hopkins’ tributes hover at the edge of these two sides, as if trying to gain perspective; we are on the surface of the water; we are on the edge of time, but the distance required to expand our perspectives, to cross over, is saturated with fantasy.

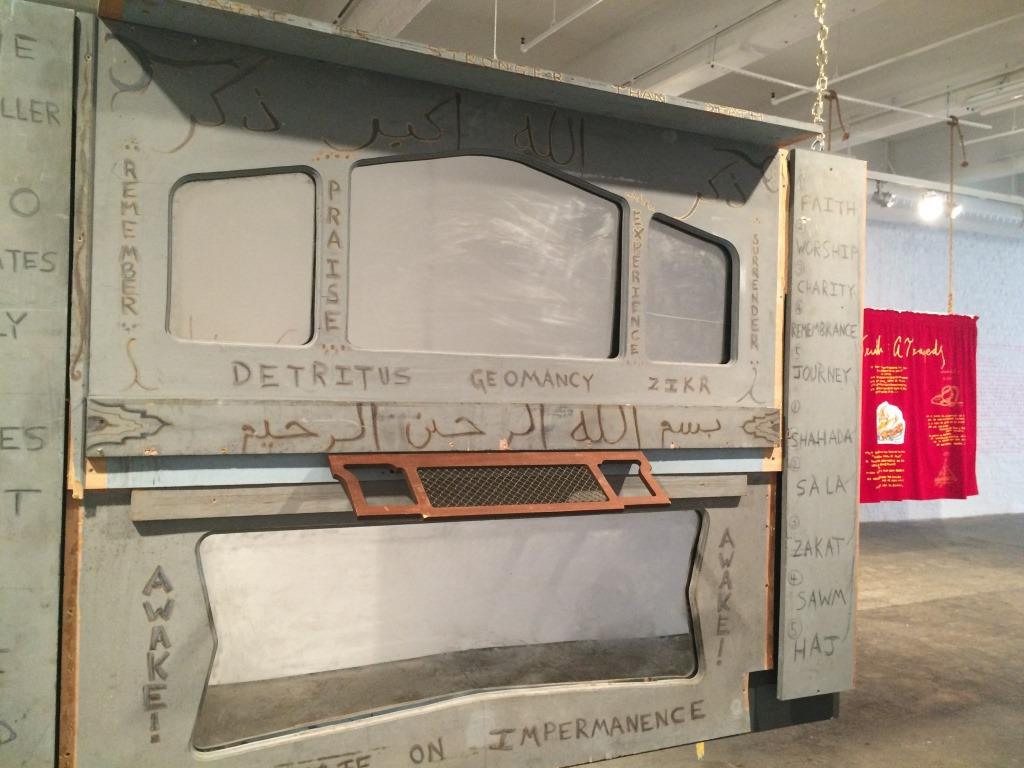

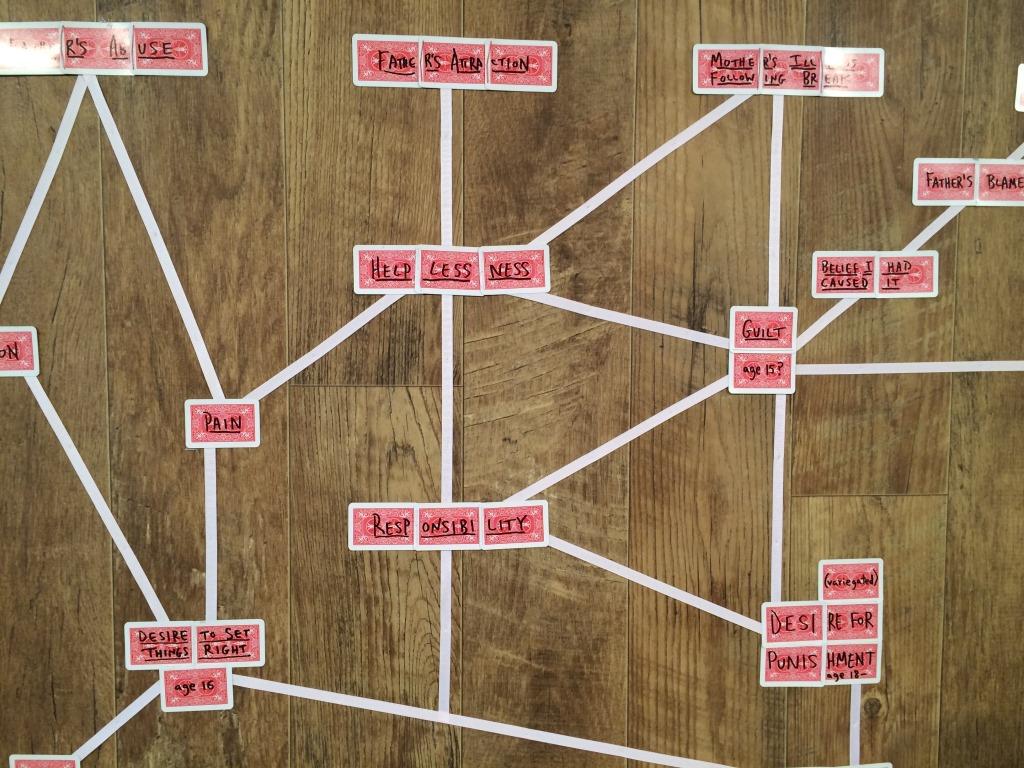

Hopkins hails from Brooklyn and has been staging large-scale music and art performances for over a decade. Memorabilia is concisely subtitled “an exhibit of five memorial quilts and one requiem in honor of five deceased musical performance works by Cynthia Hopkins,” and the work does, in fact, efficiently tie those performances to these remnant objects. Five ornately constructed, double-sided quilts are vertically suspended from and run parallel to the ceiling at a distance from the gallery walls. This placement enables the viewer to walk around the quilts, to see each side readily. To be clear, hers is a non-traditional definition of what is typically understood to be a quilt. Some of her “quilts” are wooden mantelpieces on one side; some sides are done in AstroTurf or plastic corrugated board. But all of them are ornately stitched, embroidered, or inscribed. Ephemera collected from performances — research notes, production and staging materials — are variously fixed onto the fabric substrates.

Since its founding in 1977, Philadelphia’s Fabric Workshop and Museum has maintained an active collection of artists’ boxes containing records of each of the institution’s past resident artist, by which each residency’s process, materials, fabric, swatches, and production notes may be saved and memorialized. With her quilts, Hopkins is in a sense responding to the character and history of that space; but it’s more than a salute to the museum’s collection of artists’ boxes. The Fabric Workshop and Museum, along with its community of artists and friends, is mourning the loss of their founder and artistic director Marion “Kippy” Boulton Stroud. Memorabilia and Unseen Evidence of Things Substantiated opened a few short weeks after the visionary founder’s passing, and both exhibitions also mark the end of each artist’s residency at the museum. Residencies at the museum last up to two years and are fully supported with staff and interns, most of whom are accomplished artists themselves; there’s a resulting atmosphere of generosity and collegiality that imbues the work of resident artists. Hopkins writes:

“This exhibit, Memorabilia, will serve the purpose memorials are intended to serve: to celebrate, and put to rest what is no longer living (so that those mourning the loss of the person or thing can move on with their lives) while simultaneously enriching the present with a remembrance of things past (so that those who may not be familiar with the thing memorialized may potentially learn from it, or be curious about it, or shed a tear for its loss).”

Although these exhibitions were long in the making, the soulful and contemplative work in both seems to highlight the things that perennially matter: the ways we make sense of catastrophe and loss, and how we might go about creating meaning from our imagined, fractured, but no less affecting sense of the world.

Noted exhibition information: Both exhibitions, Memorabilia by Cynthia Hopkins and Unseen Evidence of Things Substantiated by Nate Young, were on view from September 12, 2015 through January 3, 2016 at The Fabric Workshop and Museum, 1214 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA