What Made Dylan Dylan?: Hibbing and Dinkytown in the American Journey

Cheryl Reitan spoke with curator Colleen Sheehy about her search for local material to fill out the big Dylan show now at the Weisman Museum

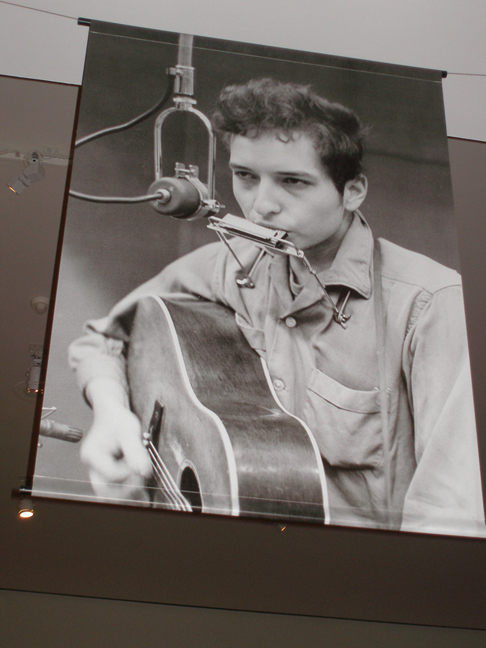

As “Dylan’s American Journey, 1956–1966″ was being assembled in Seattle, the Weisman Museum staff began amassing a collection of artifacts of their own to bring the Hibbing and Dinkytown chapters of Bob Dylan’s life into focus. Colleen Sheehy is the Weisman curator for the Dylan exhibit, which originated at Seattle’s Experience Music Project (EMP) in 2004. The exhibit made stops at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland and New York’s Morgan Library before landing on the University of Minnesota campus. Sheehy borrowed exhibit items from about a dozen people and organizations to add to “Dylan’s American Journey” in order to help visitors evoke the Dinkytown and Hibbing of Dylan’s past.

The Weisman is just steps away from Dinkytown, the small business and residential district that Dylan called home for 15 months in 1959 and 1960. “These four square blocks of Minneapolis have played a pivotal part in the world of music,” Sheehy said. In this “little Bohemia/Greenwich Village” one could find characters like beat poet David Whitaker and bookstore owner Melvin McCosh. “It was an interesting little incubator of politics and culture on the edge of the university,” Sheehy said. “There were misfits and counterculture political types, but also an intellectual infusion from students and faculty.”

The neighborhood’s music clubs, record stores and musicians introduced Dylan to folk music. He traded his electric guitar for an acoustic and played the music of Leadbelly and Odetta in coffeehouses such as the Ten O’Clock Scholar. There he picked up sets with “Spider” John Koerner and Tony “Little Sun” Glover.

In his autobiography, Chronicles: Volume I, Dylan said, “I played morning, noon and night. That’s all I did, usually fell asleep with the guitar in my hands.” He enrolled at the University of Minnesota but rarely attended classes and music took all of his attention. Dylan first crashed in a frat house, but mostly lived with a view of an alley in an austere efficiency apartment above Grey’s Drugstore, now the Loring Pasta Bar.

A listening station called “The Minnesota Party Tape,” comes from that time. It’s another Weisman extra to the EMP exhibit. Dylan can be heard singing several folksongs, including one of Woody Guthrie’s. Sheehy said, “This tape is recorded in Dinkytown in a friend’s apartment. On it you hear Dylan goofing around and joking. It’s really funny. He has a repartee. This is when he was becoming a folk singer.”

The tape came from Clive Pettersen, by way of the Minneapolis Historical Society. Pettersen, a teenager in 1960, asked to record coffeehouse folksingers on his new reel-to-reel tape recorder. Bob Dylan agreed and was recorded at 15th Ave. S.E. in Minneapolis, in a casual session with Pettersen, Bonnie Beecher, and “Cynthia” — a friend of Dylan’s.

Dylan, who was born Robert Zimmerman in 1941, played around with stage names. “He called himself Elston Gunn while he was still in Hibbing,” Sheehy said. “Dylan knew Judy Garland used to be Frances Ethel Gumm.” It was while Dylan lived in Dinkytown that he made the switch to Bob Dylan.

Sheehy heard stories of the name change while conducting her research. There are several different versions. “I was told he took the name from Matt Dillon of TV’s Gunsmoke. We’ve got a poster with that spelling.” The exhibit also boasts two copies of the folk music magazine Little Sandy Review, the first publication to announce that Dylan was using a pseudonym.

Dylan discovered the work of Woody Guthrie in Dinkytown. Dave Whittaker, who Dylan called, “one of the Svengali-type Beats on the scene,” lent Dylan Guthrie’s autobiography, Bound for Glory. Hearing the songs, learning Guthrie’s work, and reading the autobiography sent Dylan on a quest to New York City to meet the celebrated folksinger. It was a journey that took Dylan away from Minnesota permanently.

Meeting Hibbing High School English teacher B. J. Rolfzen helped Sheehy learn more about Dylan’s early years. Sheehy recalls listening to Rolfzen talk about “going out to the graveyard and reading names off the graves because he loved the sound of words.” While giving Sheehy and others a tour of Hibbing, Rolfzen took them to the Hibbing High School and showed them his former classroom. “He gave us a poetry reading and a little poetry lesson. It was so unlike any other tour.” Once, on one of her 10 trips to Hibbing to research the Weisman portion of the Dylan exhibit, she visited Rolfzen at his home. “I was amazed to find him reading Milton’s Paradise Lost just for the pleasure of it,” she said. “Who reads Milton for pleasure?”

Included in the EMP exhibit are Rolfzen’s desk and two pages of an essay the 16-year-old Dylan wrote on the Grapes of Wrath for Rolfzen’s class. Entitled “Does Steinbeck Sympathize with his Characters,” and written in Dylan’s neat handwriting, it demonstrates the rigor of the education Dylan received. “B.J. doesn’t give him an easy time,” Sheehy said. She read outloud Rolfzen’s written comments, “I think more could have been done with this, don’t you? As a whole, however it was quite good.” Dylan got a “B” on the paper.

“B.J. is an extraordinary teacher,” Sheehy said. “He made literature come alive. It isn’t just dead words to him. He reads poetry to learn how to live life. I think Dylan must have picked that up. Just to see someone like B.J., who was so passionate about what he was doing, is really inspiring.”

Pictures and artifacts from Dylan’s youth are joined by photos and paintings of the Iron Range. Sheehy acquired an additional gem, an audio recording of the young Dylan singing rock and roll in his Hibbing living room.

In addition to the Dinkytown and Hibbing material, the exhibit covers Dylan’s life from 1960-1966. A section on Greenwich Village contains photographs and authentic posters from Dylan’s earliest shows. Inside listening booths, each holding a different Dylan album from the period, museum visitors can choose individual songs. Dylan’s guitars, film clips, typed and handwritten lyrics, rare concert posters and handbills, signed albums, and dozens of photographs add to the material.

One of the things that surprised Sheehy during her research was that “Everyone’s got a Dylan story.” During the years she conducted research for the show, she heard dozens of them, “From ‘I saw him in the grocery store’ to ‘he was at a party of some of my friends.’ ” Sheehy said she understands Dylan’s desire for privacy. He’s known for his distaste of reporters and intrusive fans. “We don’t need Dylan to come back to Minnesota for us to enjoy this exhibit.”

Bob Dylan’s American Journey, 1956-1966 continues through April 29 at the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, 333 East River Rd., Minneapolis, MN, 612-625-9494