Wendy Red Star: Reservation Pop

One could be forgiven for making the visual connection between Andy Warhol’s candy-colored pop art and Wendy Red Star’s rez cars and houses series, but where Warhol created his images from a place of privilege, Red Star's vivid works celebrate the rural, lived material reality of some of the least-celebrated communities in the US

Single, cut-out images of objects draw the eye first to their color and shape, and then to the arresting contrast with their matte colors. These are familiar objects broken down to their basic, two-dimensional representations and made both alluring and disconcerting by the imperfection of the objects themselves, their unusual colors, so saturated and strange.

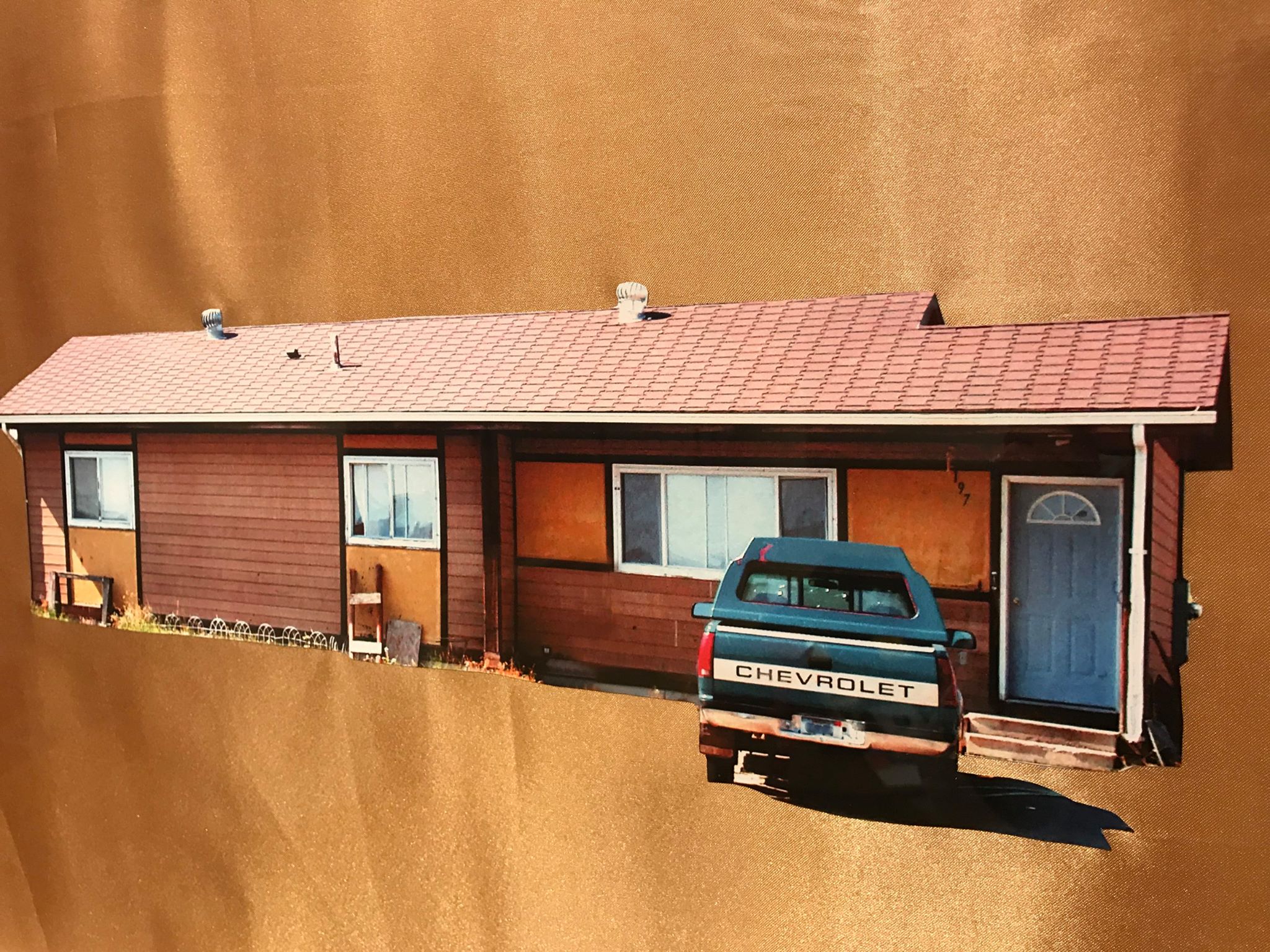

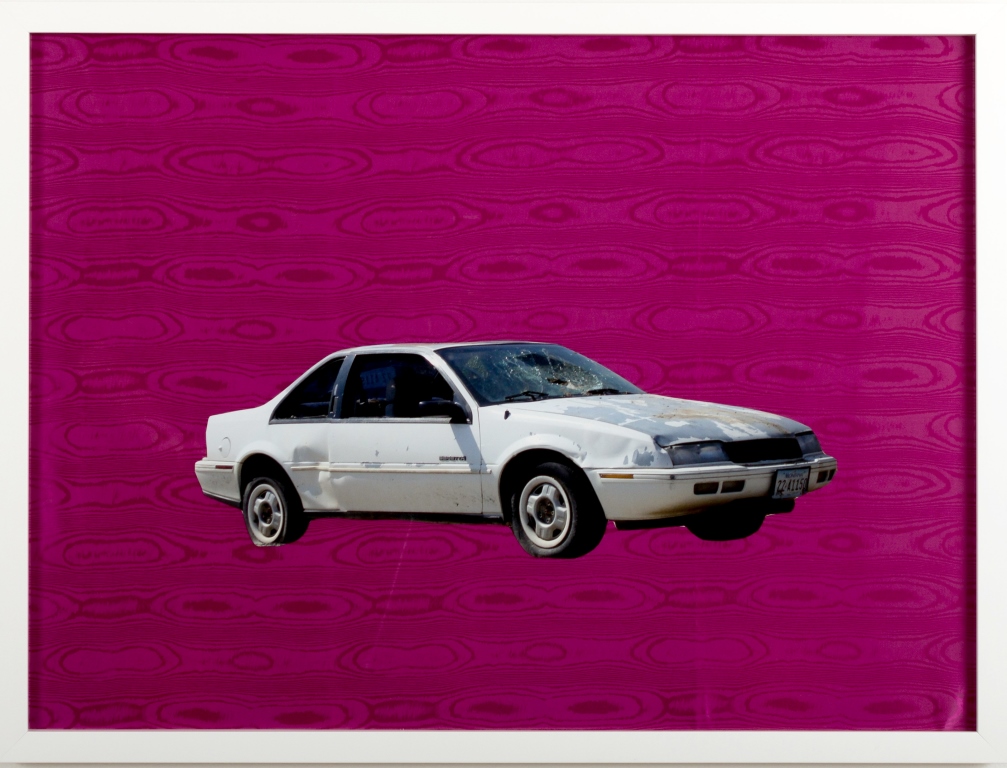

One could be forgiven for making the visual connection between Andy Warhol’s candy-colored pop art prints of both the ordinary and the famous and Wendy Red Star’s rez cars and houses series, shot in the brilliant Montana light in the summers of 2007 and 2008. The cars and especially the homes—cobalt, burnt orange, peach, flamingo pink, gold—are mounted on colored satin, evocative of a late 1970s suburban interior decorating aesthetic. The visual connection to Warhol’s sometimes garish color choices belies the truth of the rez homes: the rez home colors were not chosen by their occupants, or by the artist, but rather by the U.S. Government. They were, in fact, imposed colors. One could argue that neither did Warhol’s subjects/objects choose their own palettes—Warhol did—but Warhol’s colors weren’t selected because they were the least common denominator. Wendy Red Star’s father speculated that the colors of the houses were the result of the government buying the cheapest paint available, thus the motley palette, found nowhere but there. These were cast-off colors, suitable only for rez homes, and applied in staccato fashion to each of the three architectural styles found on the rez. That the home’s occupants chose not to repaint them is itself a form of resistance, its own kind of agency, a refusal to assign value to the choice and not to expend effort undoing yet another imposition.

It is here that any connection to Pop Art and Warhol ends. Whereas Warhol created his pieces from a place of privilege—a white man living in New York City who could flaunt both his disdain and his awe for gore and celebrity—in contrast, as Red Star says, “These are my people. This is my community. This is my family, and these are their homes and lives.” The setting is rural, highly impoverished, stark, and is the lived material reality of some of the least-celebrated people in the U.S.

One thread in much of your work is beginning with a single object and re-working it as an act of transformation and communication. What drew you to the houses and the cars?

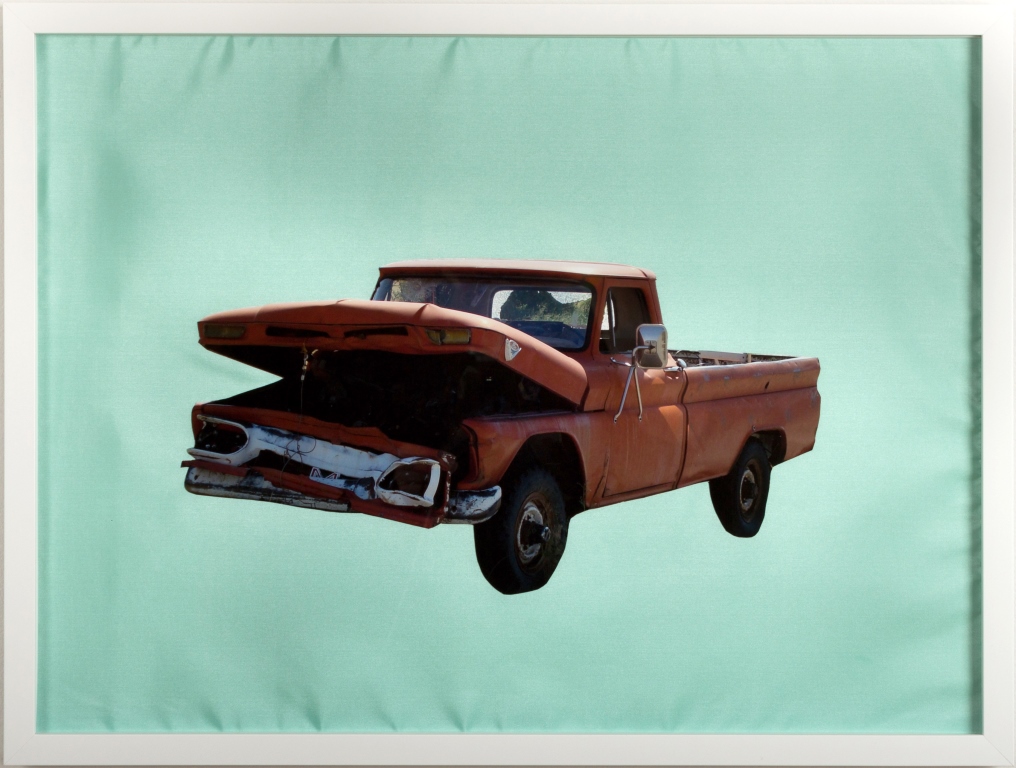

The series started with the simple questions: “why are there so many broken down cars in front yards here?” and “why are the HUD houses painted such bizarre colors?” The questions led me to investigate and document cars and houses in Pryor, Montana, a small town on the Crow reservation. As I worked, owners of the cars and houses would tell me stories: some were funny, some sad, and they all brought the cars and homes to life, transforming them from “objects” into “subjects.” From there, the project developed into what it is now: a series of photo-based works isolating each car and house down to a single entity, allowing the viewer a closer look at the details and flavor of each image.

Red Star finds both humor and humanity in the images and the stories attached to them: the personal touches of the serapes hanging in the windows, the fact that the toughest guy on the rez lives in the pink flamingo house, how the Crow transformed the use of the cars, after they had ceased to function as modes of transportation.

Tell me about the rez cars. I know you have some great childhood stories about them. You had your own car that you “drove,” right?

Yes! The rez cars were one of my favorite games to play with my cousins. On my father’s property there were three rez cars. I liked the car with the 8-track shaped like a jellybean. Each of us would pile into the cars which were parked in a row and pretend to drive off to faraway places like California, New Mexico, sometimes even outer space. We would spend hours in them, even eating our lunches there. If you were lucky you might take in a stray rez car like the time my father’s cousin hit a deer near my father’s ranch, totaling the car’s front end. The car was pushed to my dad’s yard with a promise to be picked up the next weekend. Ten years later, my father had it towed to the nearest junkyard. Sometimes a rez car becomes a painful memorial for a lost loved one. I learned of a family who keeps their son’s car parked in front of their home as a final memory of him. Their son’s car had broken down so he parked it at his parent’s home and hitched a ride with a friend to Billings. He and his friend got in a rollover accident and died en route. The car has been parked in front of their home for many years.

The cars also function as storage vessels. Can you talk a little bit about that as well?

I was obsessed with riding the ranch horses, sometimes riding up to three a day. In the summer, I could spend up to eight hours at a stretch riding around Pryor with friends. I often rode my horse to a friend’s home about three miles away. Once there, I would tie my horse to a post, knock on his bright burnt orange house and wait for him. He would get Socks (his horse), walk over to the nearest rez car in the yard and pop open the trunk where all his horse tack was stored. I would wait for him to tack up and off we’d go, racing away in the hayfields, climbing the bluffs, or playing tag in the river.

The rez homes images have not been color-enhanced. This is how they exist in the world: brilliant, otherworldly, bewitching, in spite of the obvious poverty they demonstrate. By pulling them out of their context on the Crow reservation, Red Star is deliberately mimicking what has been traditionally done with so much Native art: pulling it out of context and recasting it as a stand-alone object, whereupon it loses its original meaning. But this is not her only goal here: she is taking something many, including the artist herself, might at first identify as a sign of oppression and despair and instead makes it alluring. The colors draw you in, make you look closely: what is this place? who lives here? what’s going on?

How does this work resonate with other projects you have done around the meaning of objects in a particular place, and indeed the meaning of place and community?

My work often looks at the normalcies of everyday Crow life. The mundane that connects Crow people to all people, and connects all people to a common humanity. Taking a closer look at each house and car gives clues to the lives of the owners. The way in which the front yards are kept, the dents and dings in the cars, and the objects in the car all give clues to the community, environment, and life on the Crow reservation. My work strives to tell stories about my community, Native people, and what many people might not understand about typical Native living.

As is often the case in Red Star’s work, the heaviness the viewer might feel about the poverty on display, is mitigated by her winking humor and the stories which accompany the work. She reminds us that the Crow are not people fixed in a static past and that objects which might have meanings in one context can be transformed elsewhere, whether through physical alteration or an alternative use. Wendy Red Star’s images here seek to capture those evolving meanings and contradictions, a project far more complex than an ode to celebrity or consumer culture.

Do you situate your work at all in the context of the oil pipeline controversies and political activism? The images were taken well before the current protests—do they have a place in that conversation?

The reservation cars and houses are not a direct conversation but because of the commonalities all Native people share with the U.S. government, many of the images allude to the consequences of an oppressed people and culture. Much of what I have photographed helps explain situations like the pipeline controversies and political activism—that these people who have already given up so much are asked to sacrifice yet again. Oftentimes my work is labeled political even if I am just documenting my own environment which may seem political to the colonial norm but benign to me. I am an observer of my world and whether or not my documenting it through art is understood as political, it should certainly be understood as reimagining what can initially appear shabby or discarded as something resilient and alive.

Related exhibition details: Documenting the Rez Cars and HUD Houses of Pryor, Montana (Crow Indian Reservation), new work by Wendy Red Star, is on view at Bethel University’s Olson Gallery from April 6 – May 27, 2017.

Cynthia Gladen has a doctorate in early modern history with a specialization in Italian history, art, and paleography. She is a freelance art writer, editor, and translator and has worked on a wide range of projects from artists’ TED talks and exhibition catalogs to translations of Boccaccio and 15th c. Venetian galley auctions. She has a particular interest in interdisciplinary studies incorporating art, social history and creative communities. She lives in Portland, Oregon.