Warhol and the Art of Making Money

Inspired by 'Andy Warhol in Minneapolis,' with a medium at his side and a bunch of questions about art, funding and politics, Nathaniel Smith peers into the hereafter to get the Prince of Pop Art's take on how work is bought and sold, in his own words.

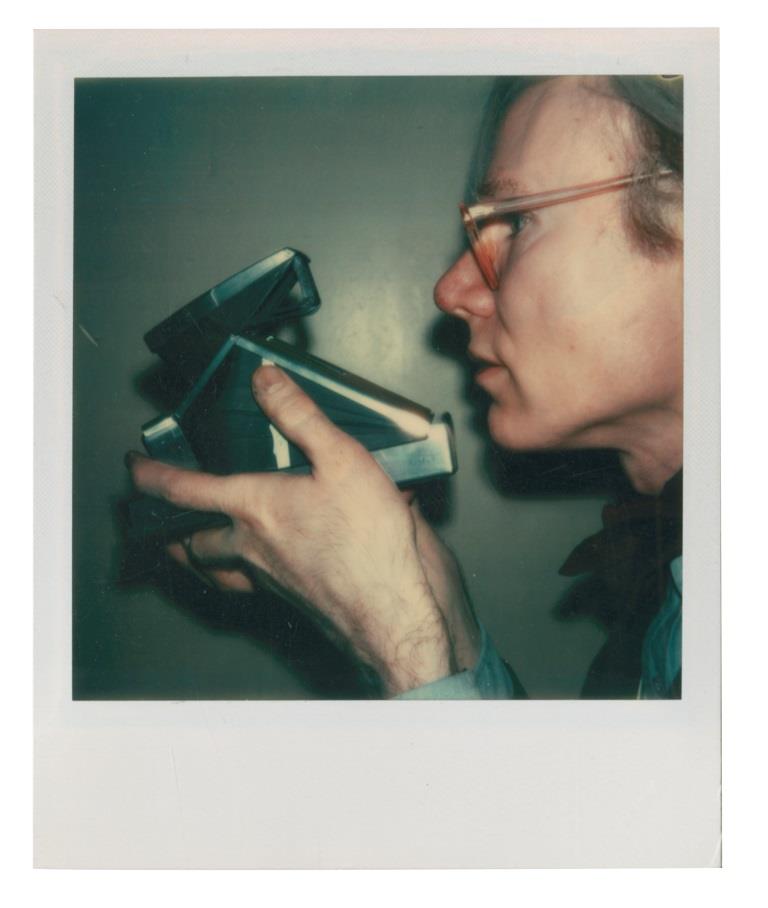

There’s a unique exhibition on view now at Aria, located in the Minneapolis Warehouse District: one of the largest presentations of work ever seen in Minnesota, by one of America’s most famous artists, Andy Warhol, opened there last weekend. The exhibition, titled Andy Warhol in Minneapolis, is the first physical stop in the Andy Warhol at Christie’s series, and it closes soon, March 23. The show includes more than 50 paintings, photographs, prints and works on paper by Warhol, among them a selection of pieces originally featured in Warhol’s only previous showing in Minneapolis at the Locksley Shea Gallery in 1975.

Not only do we rarely receive these types of collections by major artists, we rarely get to enjoy the debate that surrounds the modern art auction. Initially, some balked at Christie’s auction house being tapped to handle the sales of the Warhol Foundation’s remaining works, but most of those objecting were subsequently mollified by the fact that the majority of proceeds from those sales are being used to fund art projects, spaces, writing and artists themselves. And as of seven days ago, Christie’s online sales of Warhol’s work totaled $2.7 million, twice the pre-sale estimate — money which will, in turn, go toward funding the Foundation’s many grant-related projects.

The Birth of a Foundation

Guided by Andy Warhol’s quote, “They always say time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself,” the Warhol Foundation has done an admirable job in preserving the artist’s legacy and to advance the visual arts. After Warhol’s death in 1987, immediately upon its establishment, the foundation donated 4,000 pieces to the permanent collection of the (then future) Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the largest museum dedicated to a single artist. They have since been slowly selling off Warhol’s works to create an endowment for the non-profit and for donations totalling more than $250 million to various visual arts-related and cultural causes. Shortly after announcing that they would be ending their Warhol authentication program to increase focus on philanthropy, the foundation set in motion plans to liquidate all remaining art assets; in addition to the money directly raised from sales, the foundation could save the funds usually spent on insuring and storing the work. Citing an increased need for funding because of budget cuts to the arts during the recession, the Warhol Foundation has stepped into the breach to become a premier funder of artists, exhibition spaces, curators and arts writers.

In an incredibly brief statement at The Brooklyn Rail, former Museum of Contemporary Art, LA curator Paul Schimmel ruminates on the increasingly important role of artists’ foundations in supporting contemporary artists; these are philanthropic organizations emerging from the estates of artists like Krasner, Pollock, Gotlieb, Warhol, Rauschenberg and, recently, Mike Kelley. Schimmel says, “With the hundreds of artists’ foundations already existing in the U.S. and many more to be formed by the wealthiest generation of artists ever, their legacies will become among the most important not-for-profit institutions to directly support the arts.” This certainly is the case with the Warhol Foundation; in retrospect, Warhol famous statement, “Making money is art…,” begins to read more generous than materialistic. Schimmel says, “Surely one of the great bonuses of the commodification of art is that the artists can and are making a huge difference in the lives of future generations of less commercialized artists.”

In The Shadow of Big Art Business

Given the fact that we’re in an age when Kickstarter funds more artistic and cultural projects than the National Endowment of the Arts, what could be more fitting than a redistribution of funds from wealthy artists’ estates to their still-struggling brethren? There is, without a doubt, something appealing about the idea that the most successful artists of their day might eventually fund the careers of future artists. What is ironic is that any artist making work valuable enough that it might someday subsidize a foundation in their honor likely gained that very wealth at the expense of their contemporaries — recently through the aid of auction houses like Christie’s. The fact is, while it’s true that some living artists sell works for millions, the vast majority of working artists never reach the point where they earn a living from making art. And while the Warhol Foundation will indeed be aiding contemporary art as a whole, it does so by allying itself with one of the largest auction houses in the world, whose 2012 earnings topped $3.5 billion.

There is no doubt that art fairs and auction houses have severely disrupted the gallery system in the last fifty years. In and of itself, that isn’t necessarily a problem: any business that cannot keep itself afloat probably should not remain in business. The major issue is this: at the same time auction houses and art fairs are cornering larger market shares, they have little interest in cultivating artists’ development or offering career guidance — something important, in the larger sense, for all of us who have a stake in the arts and culture (and, it should be noted, something central to the Warhol Foundation’s mission). That’s been the domain of the traditional gallery system. Arts consultant, writer and researcher András Szántó explains that “galleries’ core strength is its commitment and close-up attention to the process of identifying and nurturing talent and prices. Where [galleries] lose out is at the high end. That’s where the business demands vast capitalization and global operations muscle. Few galleries can provide this.”

Furthermore, Szántó reminds us, “The gallery system has had a phenomenal century-long monopoly on validating artists and marketing their works. Now, faced by the globalization of wealth, mounting values and production expenses, and an untenable proliferation in the number of galleries, something clearly has to change.” This is capitalism at its core: with emerging markets and new wealth comes the identification of art with status — namely, the rise of conspicuous art consumption. Most galleries have neither the global reach nor the infrastructural support for logistics that Christie’s can marshal – particularly as concerns issues of transportation of artworks, evidence of provenance, security, and financial reliability. The appeal of partnering with a big auction house rather than with a gallery is entirely understandable. The fact remains, however, that by strengthening Christie’s, the Warhol Foundation is inadvertently further undercutting the market share of galleries and, by extension, the artists whose professional and creative development those galleries foster.

By partnering with a big auction house like Christie’s to sell the artist’s work, the Warhol Foundation is inadvertently undercutting the already dwindling market share of galleries and, by extension, the artists whose professional and creative development they foster.

I don’t have a tidy conclusion to offer; there aren’t clear solutions to this conundrum. On the one hand, it’s the way of the world – it’s just business – and that doesn’t change. On the other hand, didn’t Warhol himself say “They always say time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself”? Perhaps I’m being naive — I am, after all, writing this from the Midwest, a place whose artists are seldom as directly affected by the vicissitudes of the global art market as those living on the coasts.

But I still wonder: How transformative would it have been if the Warhol Foundation, an organization whose dedication to support of the visual arts is undeniable, had chosen to change the way major collections of art are sold? What if the foundation had used the clout of Warhol’s collection to innovate outside the existing and inadequate avenues for selling work and fostering artists’ careers? Can’t we do better than offering an unsatisfying choice between a faltering traditional gallery system and big ticket art auctions to serve those ends?

Getting Some (Unorthodox) Answers

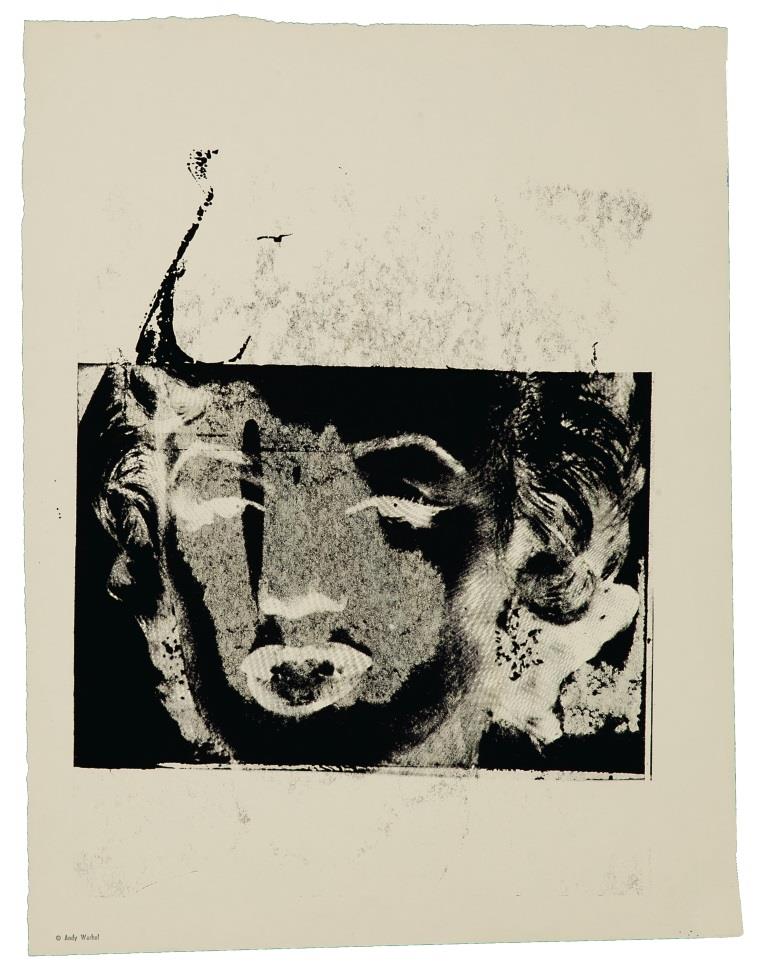

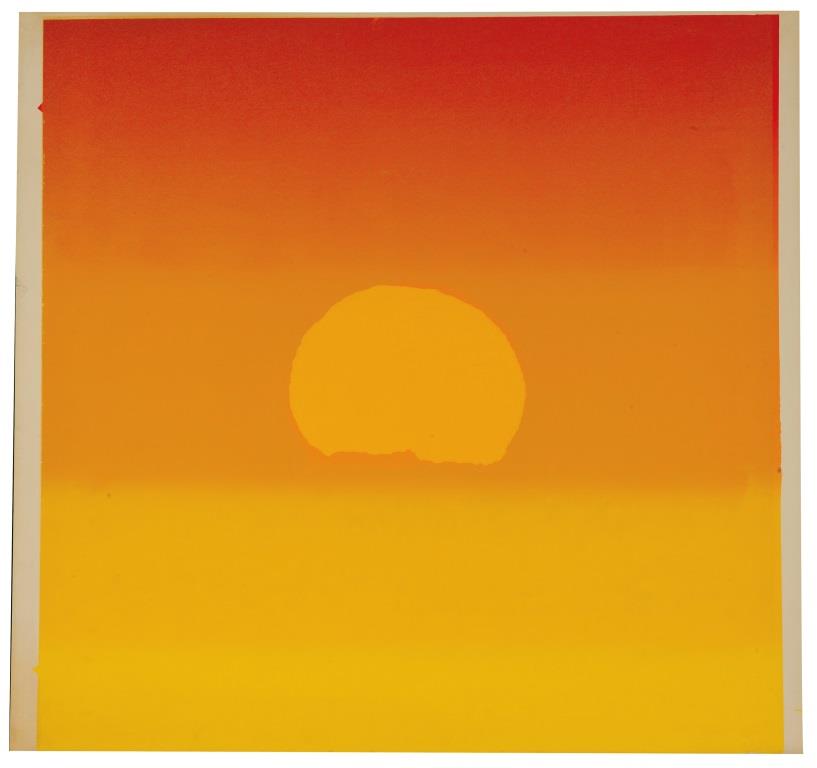

Thinking all this over, I began to look through Warhol’s works. And I realized while all of the finances and politics surrounding the collection do matter, of course, they don’t matter as much as the images he made. It’s a recurring theme with Warhol’s work: Nothing is ever as superficial or naïve as it first seems. It’s just as true that his images are neither as serious or as dire in their meanings as they’re often made out to be.

All this reminded me of an experiment I conducted several years ago, where I interviewed Mr. Warhol with the help of Minneapolis-based spiritual medium Janice Carlson. So, I returned to her recently, and from the hereafter, the Prince of Pop Art once again granted me an audience. The medium was able to give clearer answers this time around, it seemed, but the reader should note that who’s speaking when gets a little murky sometimes. I am technically interviewing Janice Carlson, but she is also interviewing Warhol, and occasionally their responses alternate between one and the other fluidly.

Nathaniel SmithCongratulations on your most recent show, Mr. Warhol! Since this is a rare opportunity, I first want to ask how you feel about the Christie’s exhibition?

Andy Warhol (through Janice Carlson)It really shows everything from A to Z, a wide-range…and in black and white…

NSDo you notice or care much about what people think of you now that you’re on the Other Side? Do you still pay attention to what’s said about your work?

AwYes.

NSI know you dreamed of your legacy continuing in the form of support for the visual arts: Do you think the people protecting your legacy are doing the job sufficiently well?

AwYes. The press sometimes skews perspectives, but there is not much you can do about that.

NSAre you famous in heaven?

AwYes, amongst artists, I am particularly treasured. Everyone is an artist here. No one paints. There’s no bodies. Everyone just moves light.

NSI’m not sure if you are keeping current with music and culture, but fame is an even bigger theme now than when you were working. Do you think that artists should still be looking for inspiration from fame?

AwFame is a byproduct of good art.

NSThere has been some controversy and also some immediate success that’s come from your newest show. Do you think the two are related?

AwIt’s inevitable. Like Yin and Yang, without controversy there’s no press…

NSFor your recent show, Andy Warhol: 15 Minutes Eternal, your iconic painting of Mao was banned from the exhibition travelling to China. Why do you think that was?

AwWhen things are forbidden they are more interesting.

(Janice Carlson): He also is saying that the Chinese government censorship will not last much longer, no more than a decade more. That the people are too strong now, and too educated to allow it…

NSHow do you feel about the term ‘selling out’? Really, isn’t it true that most of us artists want to communicate through our work, be appreciated for it, and ultimately, to make our living from it?

AwSome of what I did was commercial. Some of it was popular. Selling out is what others do, I just used topics that were popular. Some of that was very funny…it was all wallpaper.

NSThe first time we talked this way, you mentioned that you are still making work. What are you working on now?

AwWorking on a Mount Rushmore sculpture with the faces of more important people, faces not limited to American history, religious figures throughout the ages. You can always see my signature.

(Janice Carlson) When we die we become subatomic matter, the closest similarity we have on earth is light. So everyone creates using lighting, but with more 3D properties, more iridescent, more colors because they have a broader spectrum.

NSWouldn’t that be 4- or 5D then?

Aw(Janice Carlson) They are not on a temporal plane so there is no time…

NSMr. Warhol, do you have any regrets from your life?

AwNo. I was a mirror.

NSLast question: Did you really know the Velvet Underground was going to be that good, or can you admit you just got lucky?

AwUm. No.

(Janice Carlson) He sounds very intuitive.

Considering how much of the future he predicted in his work, I have to agree. Thanks, Andy.

Noted exhibition details and related information:

Andy Warhol in Minneapolis is on view at Aria,105 North 1st Street, Minneapolis for one week, from March 16-23, with viewing hours from 10 am-6 pm. Admission is free and open to the public.

Janice Carlson is a psychic medium and the author of SOUL SENSING: How to Communicate With Your Dead Loved Ones, the first and only book so far to help people develop their own soul-sensing abilities.

Andy Warhol is widely-considered to be one of the most famous artists of all time. His works in photography, film, music, painting, drawing and screen-printing exemplify the cultural norms of their times, and have become some of the most collected, and expensive, works of any artist.