The Prolific Vision of Frank Big Bear

Critic Ann Klefstad weighs in on the new exhibition of drawings by 2008 Bush "Enduring Vision" award-winner Frank Big Bear--the first large collection of his artwork to be displayed in over a decade--on view at the Tweed Museum in Duluth through March 22.

Multiple worlds fold into each other in Frank Big Bear‘s brilliant work. It’s hard to comment on this show; as testimony to a long life lived in relentless service to vision, the work’s passion and intelligence is totally humbling.

“I believe that I’ve paid my dues as a parent, as a taxicab driver, as a native, as an artist, as a survivor and as a human being,” Big Bear wrote in materials for this show. “I’ve earned the right to believe what I want. No one can tell me, ‘that is not the native way,’ because I’ve lived through it. I’ve earned my PHD (piled higher and deeper) the hard way, not vicariously.”

No kidding. For over 30 years a flood of images, created largely in Prismacolor drawings on paper, has grown under his hands, while he raised six kids driving cab. He studied with George Morrison, but primarily taught himself his art, channeling his past, his dreams, the techniques and concerns of the great modernists, as well as the visual welter of the urban streets and the woods of his past.

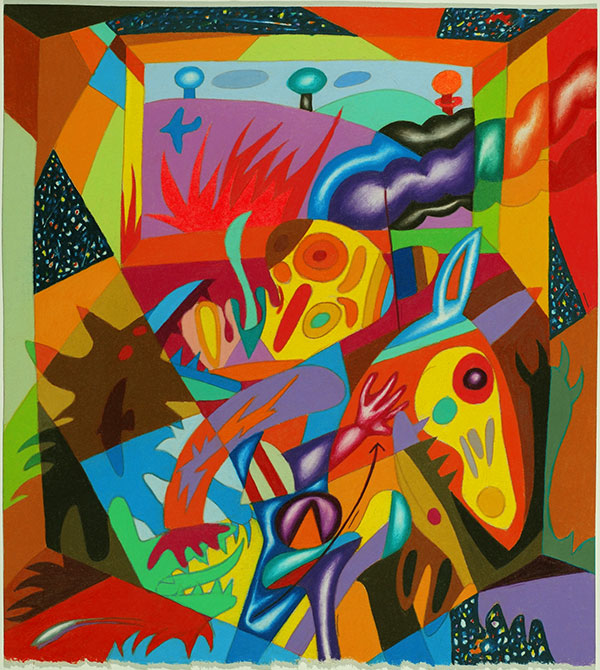

Born in 1953, Big Bear grew up at White Earth, a rez in northern Minnesota, and moved to Minneapolis in his early teens. The highly complex order of the woods, in which all is matrix and there’s no foreground, inflects his eye-boggling compositions. But his long dwelling in the art world, and his absorption of influences ranging from Kandinsky to Picasso to postmodern ironists, suffuses the work as well.

Winner of the first Enduring Vision grant award, given by the Bush Foundation, as well as a number of other prestigious grants, Big Bear no longer has to drive that hack, but it’s only been about two years he’s been free of that necessity. The past couple of years have ushered in a more radiant clarity to his work. The world in these works is the one that hovers behind the skin of any era’s reality. It’s timeless.

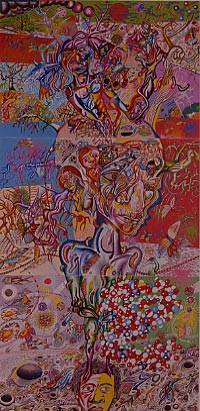

The only critique I have for this show is that it’s too small, the gallery too constricted to do full justice to Big Bear’s prolific vision. Some of his largest work just doesn’t fit and, so, isn’t present; one piece, too long for the gallery’s wall, is hung draped against it, its foot swept out from the wall. Memories, Dreams, and Visions of a Drowning Man’s Thoughts (2008) contains in each of its four-stacked panels a self-portrait in a different mode. It presents a vast span of images, reflecting his vantage as both a maker and an observer of several worlds.

The only critique I’d have for this show is that it’s too small, the gallery too constricted to do full justice to Big Bear’s prolific vision.

The selves pictured in the lower panels of Memories are made up of fragments and shards, mixed with flowers and trees; another panel presents a cartoon self, a guy in the water, near an outrageous totem pole, half kitsch and half real. A fourth image of self is a realistic portrait next to a crystalline skull a la Harrison Ford. Collaged photos – a beetle, a butterfly, a hand – appear next to their drawn doubles.

The whole work, protean and vast, serves as a kind of map of the range and thoughts and syncretic abilities of a confident intelligence. The tumbling images that spill through it – bugs and forest, birds and babes, sex and desire and the overbearing sky, the timely and the timeless – are the river of ten thousand things in which the man drowns, his life passing before his eyes.

In Memories he revisits his earlier, more politicized styles, dating from the Wounded Knee days in the mid-1980s, when his work filtered headlines through dreams and his own experience of the streets. Caterpillar Man (1992), with its chaotic dream imagery fountaining out of its tormented-looking maker’s head, culminates this era. A major change occurred in the early ’90s:

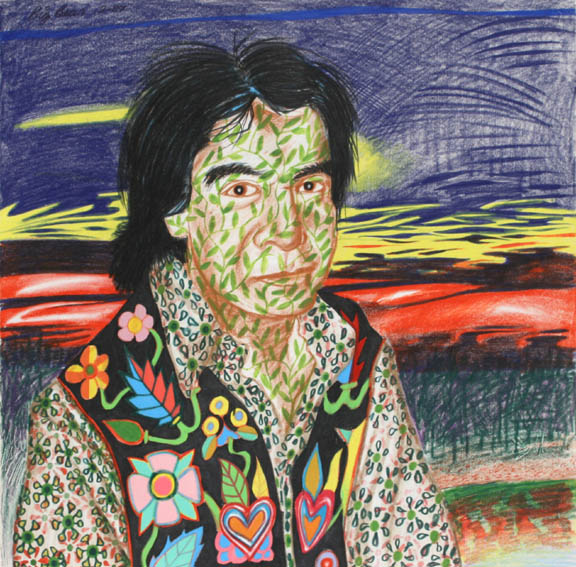

“For a long time, I might be drawing some scene from history, and [my father’s] face would appear,” wrote Big Bear of this shift. “After he died in 1992, that image disappeared.” The artist then turned his face to his own life in a new way. “Now when I draw my daughters, it’s almost like drawing myself,” he writes. “I think my portraits have a spiritual quality to them, but are also psychological profiles and hybrids of several people, including the artist.”

The inward turn spurred by the death of his father took on other forms as the need to work the streets as a cab driver receded. Drawings from the last three years or so have acquired a kind of radiant authority and timelessness that’s riveting. See the Spirit Warrior series from 2007 the beings in the drawings speak a universal language in colors that sing a high, rare music. The polished surface of Big Bear’s colored pencil is more luminous than paint and nearly glassy in its ability to transmit color as light.

The Drawings of Frank Big Bear is the first major show the artist has had in ten years, a rare chance to see a wide range of the work of this master. He’ll be big famous in a few years, if life is at all fair and maybe even if, as we all know, it’s not. If you can’t make the trip, look for the book the museum’s publishing to document it: expected publication date is January 2009; you’ll be able to order the book directly from the Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth.

What: The Drawings of Frank Big Bear

Where: Tweed Museum of Art, University of Minnesota-Duluth, MN

When: Exhibition runs through March 22, 2009

Admission is FREE and open to the public