The State of the Art Up North

Tim White takes stock of the art currently shaping the North country's cultural scene by way of the work on view in Duluth Art Institute's 60th Arrowhead Regional Biennial.

Having an ever-changeable body of water like Lake Superior in your midst on a daily basis affects people, perhaps in particular those committed to making art. It creates an awareness of matters that are tenuous, conditional, and frequently shifting. The artworks chosen for the 60th Annual Arrowhead Regional Biennial demonstrate this cognizance in subtle, at times funny, sometimes sobering ways. It is notable, the number of objects that have been torn into, abraded, and otherwise distressed. Their recurrence calls to mind the precarious balances artists negotiate — between expression and income, prestige and self-regard, utility and uselessness.

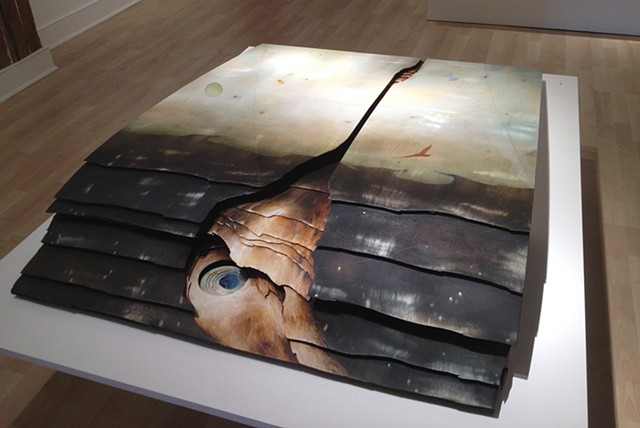

The John Steffl Gallery, which houses the exhibition, is itself a perilous space: a high ledge jutting from the fourth floor of a 19th-century railroad depot. Mary Solberg‘s Arcadia, a large painting of a lakeside bather, opens the show. The title’s reference to an unspoiled wilderness, and its subject’s static resemblance to a Florentine Madonna grounds the viewer comfortably in the space. Laid before this striking painting is Cameron Zebrun‘s North River I: a multi-layered construction akin to a topographical map. The work’s placid surface is torn into ever-deepening levels that read like a Dante-esque descent, and an allusion to the ore mining from which the region once prospered. The juxtaposition of works is a tense one: the mythic serenity of Solberg’s scene is at odds with imagery that calls to mind industrial predations that also mark this place. That disjunction complicates any merely bucolic view.

Russel Prather, Five-Minute Egg. Courtesy of the artist’s website.

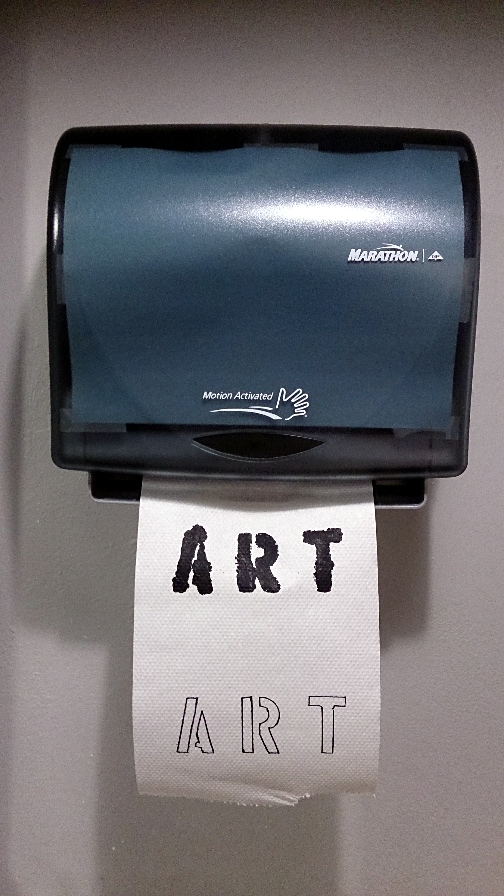

Russell Prather‘s Five-Minute Egg drifts nearby, clear sheets of acetate hung in succession that, seen from various angles, creates an illusion of suspended albumen and yolk. The work’s reason for being seems to be the sheer joy of seeing. It revealed an increasingly apparent theme that ordinary, domestic matters would here be more eminent than grand statements. and that wit would prevail over pedanticism.Take Robert Adams‘s Touch-Free Art Dispenser. The work is precisely what it is billed to be: a common lavatory paper-towel rack in which every perforated sheet is printed with multiple translations of the word art, “for collecting or wiping.” Nice.

Courtney Reints‘s untitled, is a less scrutable photograph showing a sportsman’s den: full of taxidermy, tasteful lithographs of waterfowl, a mounted buck’s head, and books with telling titles, such as “The Puritans in America.” A photo on the mantle depicts the man of the house (we presume) displaying a recently shot deer, perhaps the very one now hanging on the wall. The dialogue between this imagined person’s declaimed love of nature and simultaneous commitment to killing its constituent elements is gently ironic, yet clear. Reints shows us our homes as set pieces, rooms staged to declaim unique, sometimes discordant monologues.

Kip Praslowicz, Mt. Ashwabay, Bayfield, WI. Courtesy of the DAI.

Kip Praslowicz‘s Mt. Ashwabay, Bayfield, WI is similarly open to varied interpretations. In what might initially be taken for a postcard capture of brightly-clad people traversing a bunny hill, the sharpest image in the scene’s lovely, large-format falloff is that of the clunky, gas-driven machine which makes these recreations possible. Richard Colburn‘s Thunderbird Mine is a far more foreboding landscape, a gelid wasteland from which no phoenix could ever likely rise. It is nicely complemented by Amber Darling‘s abstract painting Red Gold II: moving, though less literal, her rugged, mostly anthracite color field is punctuated sparingly with taconite hues and bright cadmium reds that speak eloquently of waste and loss.

Exhibition curator Diane Mullin, of the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis, has arranged the works on view to create a series of comfortable niches within the gallery spaces’ awkward confines, pulling us toward a second chamber whose works are more muted and intimate. Karen Savage Blue‘s Indolent Water is a tiny, enthusiastically scratched-upon pond scene of golds and cerulean blue evocative of the in-between seasons — the stark potential of not-yet spring or autumn just after lushness has passed. Karen Nease’s Untitled (White over Grey) articulates a similar terrain of transition: what first looks like an austere, monochromatic horizon has been abraded to reveal nascent patches of vermillion. Next to works so understated and allusive, Pete Driessen‘s Standard (a Federal Reserve money bag), or George Ishmael’s Blue 2 (soot on glass) seem cerebral and academic.

Amber Darling, Red Gold II. Courtesy of the DAI.

Mullin’s other selections are more consonant, elegantly emphasizing surface textures, spontaneity, and craft. Marjorie Fedszyn‘s Untitled: Form in Paper resembles an opened chrysalis of luminous whites draped, shaped, and frayed into an arresting piece. Marcia Haffmans’s Verwerking/Processing is yet another example of materials rent asunder, delved into or, one could say, receptive. Appended to a torn canvas of gesso and glyphic writing is a letter by the artist’s grandmother. It is a meticulously embroidered reproduction conveying her family’s pre-war duress and urgency to leave. References to the region’s immigrant history, and to the richness of nearly-extinct epistolary conventions were both cogent and pronounced.

Mullin leavens the assembled works’ at times staid, Scandinavian tone with moments of irreverent humor. Tom Christiansen’s bronze Invisible Man looks like a dashing cloak for the non-figure within. Elizabeth Garvey‘s encased leaf (yep, just a leaf) priced a mere $500, is a sly take on Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God — Up North, such humble and plentiful natural artifacts supplant diamond-encrusted skulls. Tim Byrns’s ebullient rooster-like thing of carved and polished burl is about as wonderfully useless as art can get. During my second visit, a grocery list sat on the artwork’s pediment and, intentional or not, was a perfectly apt addition. David Lee Thompson’s Foreshortened Foresight Plow is a monumental twining and vining thing, which might serve its stated purpose of “navigating the drift,” or any of the other too-numerous listed reasons; I thought it nicely cued up the cheerful wall of children’s art just past the exit.

Elizabeth Garvey, Draft. Courtesy of the artist’s website.

I watched a cleaning woman inch her mop across the vast floor below the gallery’s vertiginous ledge. After taking in so much vernacular work, it seemed perfectly fitting — nearly an installation. I listened to the heating system’s strained exertions to fill the cavernous space while I wondered about what I’d just seen. This biennial rewards intentional, investigative interaction with the work but doesn’t offer definitive resolution, asking more of the viewer than passive admiration of prettiness or virtuosity. This iteration of the Arrowhead Regional Biennial deftly realizes Mullin’s aspiration to “bring glimpses of our differences and similtudes in eye-opening and humbling ways.”

This year, there is a companion exhibition at the nearby North Shore Bank of Commerce, with selections from past biennials coordinated by venerated curator, artist, and teacher John Steffl (in whose honor, the gallery housing the current biennial is named). In this temple of capitalism, where everyone from the palace to the gutter brings their earnings, you’re as likely to see a gritty, Hopper-esque streetscape as you are a Lake Superior idyll.

Karen Savage Blue, Indolent Water. Courtesy of the DAI.

From a warm boardroom overlooking a frozen avenue, Mr. Steffl professed his firm belief in the intrinsic (and, when merited, extrinsic) worth of art objects. As well-wishers and employees (including a beaming Larry Johnson, the bank’s president and the biennial’s benefactor) popped in to greet him, Steffl animatedly proffered subjects. We discussed currently under-regarded concepts such as cultural capital, patronage, and stewardship — values he feels we have ceded, to our detriment, to a glutted media landscape, to an emphasis on audience experiences, and to notions of art as social practice.

Courtney Reints, untitled photograph. Courtesy of the artist’s website.

Steffl stressed the critical role that institutions and professionals charged with preserving a public trust have in sustaining a region’s creative culture, and its ability to cultivate and retain committed makers. And though his chosen home might be considered “less mythologized, less celebrated” than other, more typically lauded centers of culture, this region nonetheless thrives. Even as he lamented the avarice of the “capital A” art world and its shift towards happenings over salient works of art, his sometimes jaded perspectives seemed more a means to draw one in rather than intransigence or an inability to reconcile change.

We talked about the constraints in both creating and drawing from a corporate collection (however locally-rooted and public-spirited the North Shore Bank’s is) and, specifically, about lowered denominators and increased sensitivity to patrons’ at-times delicate sensibilities. And yet, even within these limitations, are possibilities for restoring the luster of neglected gems, and for moments of subversive wit. Say you have a hallowed work that hasn’t been moved from its place in a stairway for over 30 years, such as Steve Meyer’s 1970 T.R. Buffalo. Though it is a painting that has passed beneath the waves of what the art world now considers fashionable, when shown near a work more currently in vogue, such as Jim Denomie’s Buffalo Wings (wherein native horsemen herd a flock of flying chickens), the former appears newly brilliant, totemic even.

Carefully chosen placements like these, in such a banal setting, make the bank’s accompanying exhibition’s pleasures both nuanced and acute. At the bank’s entrance, Stephen Ljubovic’s Breakfast Table and Scott Murphy’s The Layoff confront you like the prow of a snowplow offering two possible metaphorical outcomes for your business here: you could have in store a lovely repast of canned peaches and Shredded Wheat; then again, you may be as a tow-headed child, oblivious to the descending wall cloud behind you. The lobby itself is ringed by bucolic scenes: the harmonious expanse of ochres and celadon greens of Robert Meadows’s Haystack sits above a humble cubicle near an unchallenging Cheng Khee Chee landscape, and Jo Kossett’s For the Birds, in which a broadly brushed sailor offers communion to a seagull.

Cameron Zebrun, North River. Courtesy of the artist’s website.

Works that are more conceptual are shown on the bank’s second floor — appropriate for a space where the complex business of conferences and wealth-management are conducted. Highlights among these works include Boyd Christensen’s ruptured white canvas, “untitled,” and Steffl’s own Snake Dream (far less Freudian in its meaning, he explained, than one might expect). And yet, however cryptic and symbolic this level of the show may be, it isn’t without warmth: Arna Rennan’s Reflections on Water is a placid wash of plum and Prussian blue rippling over a brackish subsurface. There’s even droll humor: Dorian Beaulieau’s Stoneware Tomuku Bottle, when placed next to the lobby’s humble coffee service of plastic carafes, could be a wry meditation on the nature of ceremonial objects.

A gratifying part of this experience for Steffl was discovering just how many of the artists chosen for inclusion have persisted, even succeeded in their work despite capricious audiences and a commodity-driven market. He notes that many found positions teaching, or established comfortable existences on the fringe. He was enormously proud to find “The Arrowhead Regional Biennial” noted on so many curriculum vitae — to see how the institution he fostered had become a stepping-stone to credibility (Steffl served as the Duluth Art Institute’s artistic director and later its executive director throughout the 1990s).

Steffl reserves his most strenuous enthusiasms for being given the ability to rescue works from their status as reliquary objects and return them to public view. After all, they were made by people he had dined and drank with, taught, and loved, in a place he has spent over 40 years. This expansive show celebrates the biennial program’s legacy, but it is also a generous gift to a particular community that Steffl clearly loves.

After a full morning spent blue-skying thoughts and themes, I could only later recall and pose one actual, journalistic question: How, if at all, does Lake Superior affect the region’s art and artists? True to George Carlin’s maxim that if you “scratch a cynic, you will find a disappointed idealist,” Steffl answered tersely, “The lake makes artists cold and wet,” (a mischievous smile conveyed even via email). No further elaboration was necessary.

Related exhibition links and information:

The 60th Arrowhead Regional Biennial is on view from November 13, 2014 through February 15, 2015 at the Duluth Art Institute in the John Steffl Gallery; a companion exhibition featuring a selection of previous biennials’ artists is on view concurrently in the North Shore Bank of Commerce in Duluth, Minn.

Tim White is an artist, writer, and founder of the “You are not a dinosaur” artists collective. He currently lives in Duluth, Minnesota.