VISUAL ART: Story’s Triumph

Art critic Ann Klefstad reflects on the victorious return of story to art, a triumph evidenced by the narrative-rich work of the four McKnight Fellows on view at the MCAD Gallery through August 10.

STORIES HAVENT BEEN REALLY RESPECTABLE IN ART around here latelylet’s say, from the mid-1980s until sometime last year, when everyone simultaneously got sick of ambition-made-visible as an art strategy. But now, suddenly, those artists who use narratives of all sorts in their work have become visible, even outlined in light: people like Bridget Riversmith, or Chris Larson, or Jim Denomie, or hey!the four women whose work is in the MCAD/McKnight Fellows show.

The ways in which each of these artists approaches story are quite different.

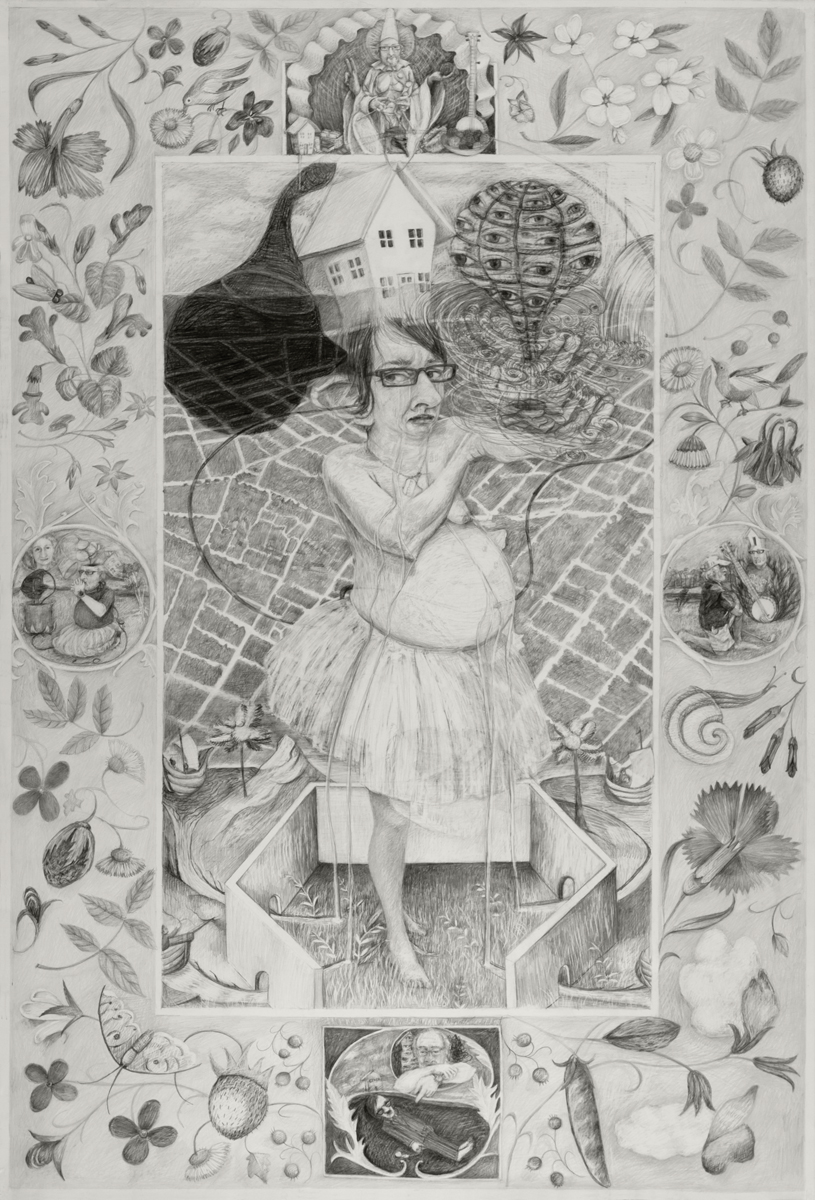

Amy DiGennaro uses autobiography nested into a book of hours, with its illuminations. Shes referred to several of these medieval and Renaissance texts, but lets look at one piece, Marilyn the Sedulous, that references one of them: the Hours of Bona Sforza.

Now, the story of Bona Sforza is emblematized by her last name: the Sforza family were the capos da capos of Renaissance Milan. Arms merchants and power brokers, they were famous for their ruthlessness, their wealth, their ambition, and their skill with poisons. Bona was a grandniece of the notorious Ludovico Sforza, who likely poisoned her grandfatherthough rumor had it the man had killed himself in a heroic bout of sexual indulgence. Bona eventually became queen of Poland; she was accused of poisoning an enemy and herself died of poison upon her return to Italy.

But her book of hours is exquisite. The Sforzas were great patrons of the arts and funders of the humanist thinker Petrarch. Bona’s little book is a resonant visual account of the intimate and spiritual concerns of a thoughtful and educated woman, as well as a resolutely incarnate record of the way such concerns sometimes play out on this earthin blood and tears, as well as hope and love.

With this for starters, DiGennaro has a huge resonator for her imagesand thats the way story works. It always plays out before the crowded hall of all the other stories that people have told. And the more of them you know, the more every molecule of the one youre hearing is electrified and, yes, illuminated.

And DiGennaro gives us lots of molecules. First, the face of the protagonist is delivered with the kind of wry accuracy that splits the difference between the style of the master of the hours and this artists actual visage, with a self-deprecating and charming emphasis on the schnozzola. Then, the details of her life are inscribed, yes, sedulously: ear canals and balloons, clocks, serotonin, sewingokay, there are children in this household! Anyone whos ever raised them will recognize these images instantly. And trees and eyes, cells and ganglia, houses and mapsimages of focus and brachiation. These take the place of the theology that enabled Bona to plot her souls course amid the carnal territories that she had to traverse.

Every one of DiGennaro’s pieces has this plethora, this layered palimpsest, that you can stare at and through. Its a lot to ask of a viewerbut then, a lot is delivered.

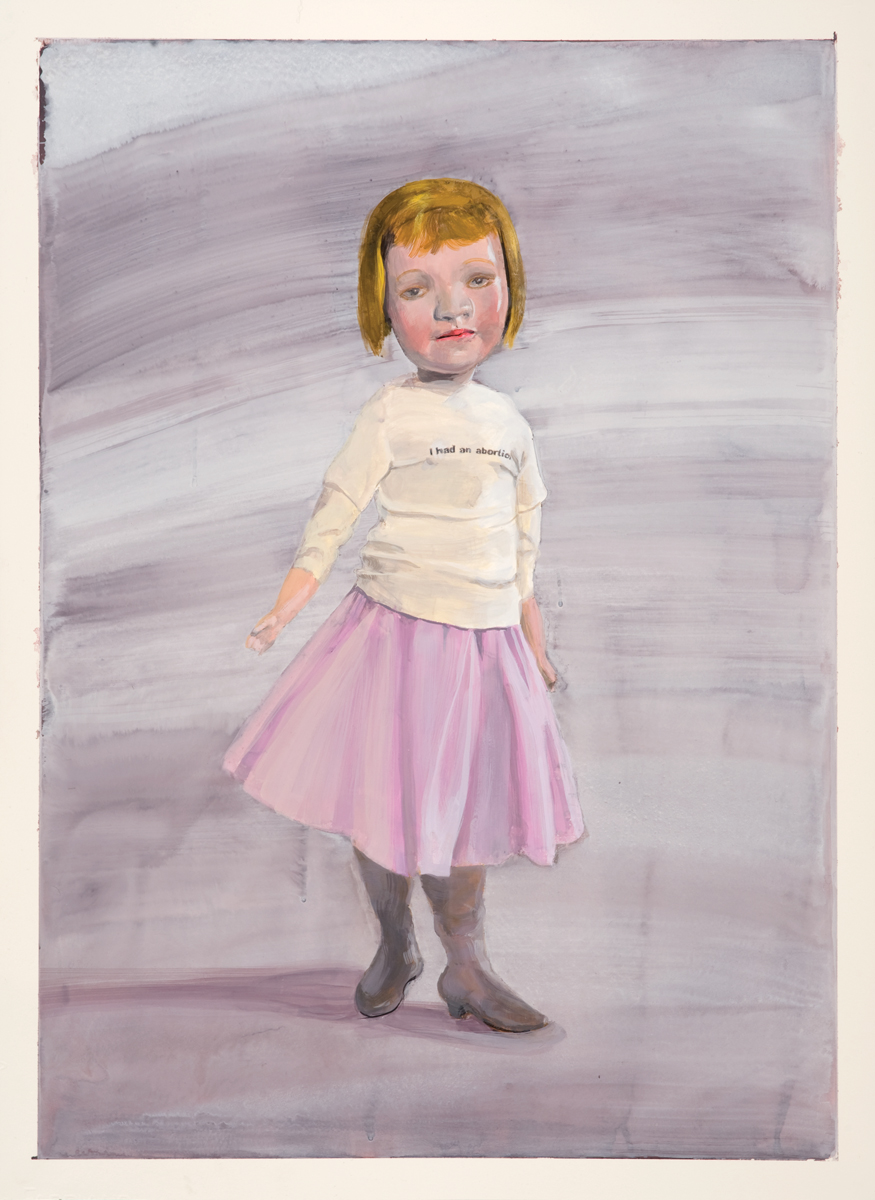

Stacey Davidson delivers a novelthe nouveau roman kind, like Nathalie Sarraute or Alain Robbe-Grillet,all texture and color, out of which the viewer’s experience is drawn and meaning intuited.

Unlike those of many nouveau roman writers, her characters have names, evocative onesKnecht Ruprecht, that beautiful rueful ruin; Lorrine; Muldoon or the Man with the Painted Face.

Davidson makes dolls, sculpts these characters, and then paints pictures of them. And the artwork is this second-order product, the painting. The process feels like the double level of making you find in the nouveau roman and in the air outside of the book itselfthe making both by author and by reader that such a book demands. You become conscious of the intervention of the fabulist, but the fictions she paints are more credible than many real lives, maybe in part because you, the viewer, are actually collaborating with her to make the story.

All of us English majors suffer from this need for metafiction. Davidson satisfies the jones in spades. Its lovely work, and sticks with you long after you leave the show.

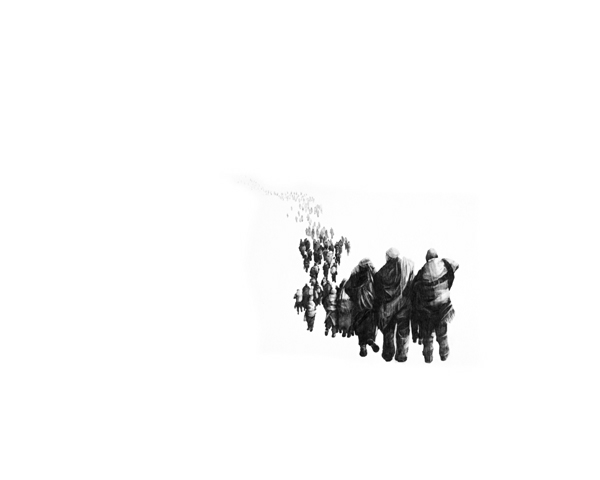

Megan Vossler works from the stories of drama, terror, loss, courage, and survival that we see, sometimes only with a glance, in newspaper and TV accounts of disaster. Her pencil drawings on big sheets of white paper have evolved, from the Reconnaissance series of 2007, one of which is shown here (On the Move) to the 2008 drawing All of Our Moments Are Stolen.

The 2007 drawing has a certain purity. It serves one purpose, and that a rhetorical one. The faceless group is distant. We could be part of it. We arent, but we could be. Its an elegant elegy.

Vosslers recent work is more difficult to take in. All of Our Moments Are Stolen is an attempt to tell a story that the storyteller has not masteredhasnt lived. The need to fake it, to gloss over the crucial unknown detail, to resort to generic gestures of abjectionis clear in this array of human beings grubbing around in a cul-de-sac of broken wood and crumbled rocks. A similar effect is seen in When Daylight Moves, We Rely on Distance. Faces can be seen at last, but the scale of their sketchy detail most closely resembles the mechanically chattered surface of the columnar broken trees behind them.

Is this a mistake? Perhaps not. The artist may be proving to herself, and to us, how distant our experience is from the extremity in the picture. However we may strain, we cant know it.

The plaster bags may represent a move away from the pictures of diaspora. They carry faint traces of their previous incarnation, red and blue threads along the seams showing where the bags they were cast from were ripped away. Again, a kind of abjectionhere, the hard physical work of destructiontries to make common cause with an experience it may be impossible to fully know, and thus impossible to empathize with.

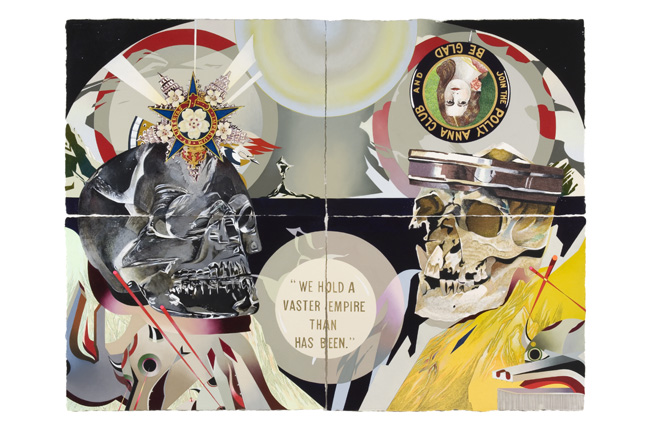

Andrea Carlsons work, as represented in the catalog, includes more than the work on the wallone of the big paintings is missing. Was there no room for it? The two skulls with their crowns are spectacular, and I would have liked to have seen them in person.

The two paintings that are on view show what were missing in the third. The tiled and richly worked surface of what, in reproduction, looks smooth and seamless is somehow moving in and of itself. The golden and silver paint, the thick ink, the difference between shiny and matteas you get close to these works, the dazzling image pulls itself apart into materiality. The painting itself, the techniques used to make it, embodies a process of transformation.

The transformation is latent in the painting, Portage, with its inert black water and still landscape with cave. Is it Platos cave? The one where we see only the shadows of the real? I wouldnt put it past Carlson to use this parable. This interpretation would account for all the wildly powerful patterning around the perimeter of the work, and would explain the title itself, “Portage.” In Carlsons world, the everyday reality we experience most of the time is charged with the breathing life of spirit, which maybe you could think of as “meaning” if meaning were alive. Hers is a pantheist world, and everyday life could be considered a portage between one realm of this living spirit and another.

Nearby is The Tempest, which suggests another story, Shakespeares play about the magician and his daughter Miranda, the one who sees the brave new world. From out of the cave that is pictured in Portage, one gazes over a formidably huge, but confined body of water, bisected by the powerful symbol of the delta, the triangleboth upright and inverted. This has been a powerful form since the Paleolithic. The meaning of these geometriesthe triangles, the chevrons, the parallel lineshas been made banal by abstract thought, but when you see pure form like this in the natural world its shocking and powerful. There is a way in which the combination of life force and abstract techne create magic. The real thing. It’s just that Carlsons way of doing it is through painting.

About the author: Ann Klefstad is staff writer on arts and entertainment for Duluth News-Tribune and was mnartists.org’s founding editor. She is a member of the Visual Arts Critics Union of Minnesota. You can get much more of her writing by visiting her regularly updated blog, “Makers.”

What: The MCAD/McKnight Visual Arts Fellows Exhibition

Where: The MCAD Gallery, Minneapolis, MN

When: The exhibition runs through August 10, 2008

Admission is FREE and open to the public