VISUAL ART: Mind Over Matter, Work by Roman Signer

Artist and critic Carmen Tomfohrde took in the new exhibition of sculpture, drawings, film and video by Swiss artist Roman Signer, and she found it to be inventive and eye-opening. (On display at the Rochester Art Center through September 14)

Six round fans arranged on the floor exhale a steady hum of air toward a ceiling in the Rochester Art Center. Suspended above them, six whiskey bottles hang from the ceiling and glide around in slow, dizzy circles, lazily riding the currents of air. The bottles labels age their contents at between ten and seventeen years, and the bottles are only three-quarters full.

Titled Bar (2007), this sculpture invites utilitarian objects to perform in a simple equation of A + B = C, where nature, gravity, and time are the agents of change. A and B are familiar household commodities, but there is mischief in their unexpected combination. Little round fans are not normally paired with partially drained whiskey bottles that hang from the ceiling, and the whole equation is facetious in a gallery setting.

This piece joins several drawings, videos, and other sculptures in a solo exhibition of work by the Swiss artist Roman Signer (born 1938, Appenzell, Switzerland), currently showing at the Rochester Art Center. There is a transitive verb in every Signer situation: one element impacts another and causes a change. His objects have basic physical properties that we can easily predict and understand. Signers deadpan humor keeps the equations precise, preventing the intrusion of trickery or excess showmanship.

The objects in his arsenal are familiar: a red kayak, a small firework, black rain boots, a red carpet, a blue barrel – these objects are never embellished with distracting ornamentation or loaded with cultural connotations, but are pared down to the representative symbols necessary for their participation in a given scenario. The red carpet must always be bright red, clean, and rectangular. A gold fringe would be out of the question, and blue shag would be totally wrong. Signer’s forms inspire none of the fondness and affection that cultivate consumer desire and consumption of Hello Kitty merchandise. Instead, the tacit simplicity and non-partisan behavior of Signers objects create an emotional distance that heightens the facetious tone of the exhibition.

Through triviality and irreverence, he teases the fear out of circumstances that could otherwise feel odious or sinister. When Signer uses gunpowder, he physically and psychologically protects himself and his viewers from any real threat of conflict or injury. Likewise, in this exhibition a small robot prowls around on the floor inside a rectangular terrain that is delineated by a boundary of red tape. A camera mounted on the robot projects live video feed on a wall nearby, enabling us to share the robots vision: it has a prime view of our ankles and the spaces under tables and chairs. Surveillance of this innocuous kind feels playful, not intrusive. Signers humor is therapeutic: he designs situations that simulate distress, but uses humor to replace the negative emotions we normally associate with explosions, collisions, surveillance, and other predicaments.

In the sculpture Wheel (1996), a bicycle wheel stands on its tire. The base of the wheel is locked into a narrow rectangular strip of cement that simultaneously stabilizes the wheel, enabling a vertical posture, and thwarts the wheels intended function. In a nearby gallery, the sculpture is repeated with the same title and a date of 2008. For this new manifestation, the rectangular pedestal is made of ice, and the configuration stands inside a giant walk-in cooler. A window on the door permits a view of the wheel suspended in the grip of ice. Recall Marcel Duchamps 1913 bicycle wheel mounted onto the seat of a stool: this combination disabled both the wheel and stool, but yielded a sculpture. Duchamp and Signer both repurpose found objects in bizarre and incongruous ways, using irony to create cultural progress out of planned dysfunction. Duchamps wheel was significant because it asked the viewer to think critically about art, a request that he positioned against the paradigms of art of the time. Meanwhile, Signers works bear similarity to Duchamp’s, but they are primarily time-based projects that are intimately engaged with their structural and natural environments. Signers iced wheel can survive only as long as temperature conditions allow.

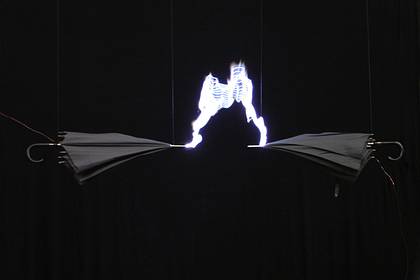

Signer stipulates every aspect of his actions and presentations, assigning objects to positions that reference both their past and present surroundings; this precise and carefully planned allocation lends a formal cohesion to his work that can sustain endless scrutiny. The Rochester Art Center includes balcony overlooks and other architectural devices that allow vistas of adjacent artworks. The fans from Bar carry sound into other galleries. First floor windows enable the robot to view an outdoor sculpture in which a red kayak (a Signer classic) has jackknifed into a conical heap of pea gravel. Upstairs, the spent conical firework beneath a cooking pot echoes the shape of the gravel mound outside. In a video on the first floor, the artist shuttles along a country road riding in a red kayak that is tethered behind a moving vehicle. Additional mnemonics abound for followers of his work: a small robotic helicopter armed with two aerosol spray cans debuted at the 1999 Venice Biennale. Now it appears in Rochester, parked quietly near the markings it produced in that earlier exhibition, when it flew in circles above flat wooden panels.

When Signer appears in his videos and actions, he is slightly disheveled and performs with neither stealth nor panache, surrendering obediently to his role in the equation. In the video Dot (2006), the artist sits before an easel in the idyllic Swiss countryside. He holds a paintbrush near his white surface, poised in expectation. Behind him a fuse burns visibly and audibly on a small explosive. Bam! The firework detonates and the artist reacts in surprise, placing a small black spot of paint on the canvas. In apparent frustration, the artist gets up to leave, and the action is complete. In this way, Signer carefully balances orchestration with chance: he prepared the surprise detonation and sat there waiting for it, but he still could not fully anticipate the precise moment at which the sound would startle him into production.

The famous exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form (Bern Kunsthalle, 1969) set the stage for Signers oeuvre. Organized by the late Harald Szeemann, this show pioneered conceptual, performance, and action art as legitimate pursuits. Walter de Maria tore up the concrete sidewalk outside the Kunsthalle, Richard Serra threw molten lead against the walls of the exhibition space, and Lawrence Weiner cut a square out of a pristine white gallery wall (again, destruction as progress). A few decades later, the terrain of contemporary art has now expanded to welcome these artistic disciplines, but Signers prolific, yet highly focused career remains somewhat overlooked in the USA. Currently a contender for the 2008 Hugo Boss Prize, the 70-year-old artist deserves further inspection.

It is worth a trip to the Med City to see this exhibition. Signers work is timeless, and it is just as rewarding for those newly encountering his work as it is gratifying for longtime followers of his career. This exhibition fires on all cylinders: formal presentation, socio-cultural significance, and art historical relevance, plus a streak of pure fun. One of the most extensive presentations of Signers work shown in the USA to date, this show is exemplary of the range of Signers activity over the years. It is an excellent opportunity to experience a number of magnetic and inventive art works by this significant artist, in a harmonious and clever presentation.

What: Roman Signer: Works

Where: Rochester Art Center, Rochester, MN

When: Exhibition runs through September 14, 2008

General admission is $3

About the author: Carmen Tomfohrde a writer, artist, and teacher currently dividing her time between Minnesota and Asia. She is a member of the Visual Arts Critics Union of Minnesota (VACUM).