By the People, For the People

Art critic Julie Caniglia reflects on the exhibition "By the People, for the People: New Deal Art at the Weisman," and on the unique American experiment in publicly subsidized arts programs from which these works spring

Are we headed for another Great Depression? Certainly plenty of people have drawn parallels between our current situation and the economic disaster that persisted throughout the 1930s (plus a few years of the decades on either side). When you consider that the prices for food and oil are climbing just as steadily as the stock market declines, the droughts, the growing layoff and unemployment rates, the stagnation in U.S. manufacturingwell, those comparisons don’t sound so far-fetched, do they? Then, of course, there’s the mortgage crisis (with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as the latest waves of that disaster now coming ashore) and a housing market that is arguably just as bad as it was during- yes – the Great Depression.

All of this grim news lends a certain air to the exhibition–whether it’s an air of foreboding or reassurance (come on, we survived the Great Depression!), take your pick.

All of this grim news lends a certain air to By the People, For the People: New Deal Art at the Weisman, on view through July 27–whether it’s an air of foreboding or reassurance (come on, we survived the Great Depression!), take your pick. In either case, on display are some of the results of an unprecedented (and unrepeated) period of U.S. government support for the arts. Works by masters like Dorothea Lange and Edward Weston have been receiving much attention, but most of the pieces in the exhibition are by artists like Lucia Wiley and Mac LeSueur, whose name recognition has faded away; some are ripe for rediscovery and others… Well, let’s just say their work serves to illustrate some of the six themes around which curator Diane Mullin organized the show.

If it’s expecting too much to be blown away by any individual work of art in this exhibition, you may instead be pleasantly surprised by other types of reactions. For instance, I found that four works (one in each of the four galleries in which the show is installed, as it turns out) provoked an instantaneous smile, each for different reasonssomething that hardly ever happens with contemporary art.

What is important is that this picture focuses on labor, on industry, and on locality. It demonstrates a drive to document and pay homage to the kind of essential governmental service that we tend to take for granted.

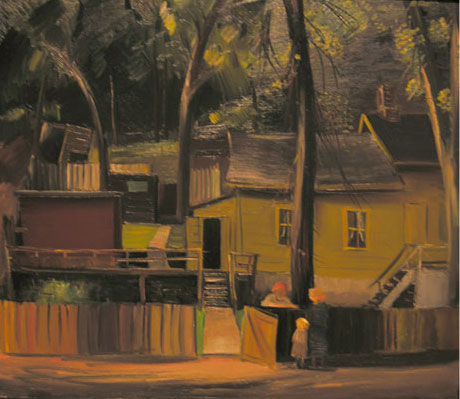

The first of those was not so much because of the artwork itself but rather its title: Twin City Sewage Station, by Glen Ranney. It’s a simple scene, depicting a couple of workers outside the titular facility, and while it’s competent in terms of aesthetic technique, the piece is hardly striking. What is important is that this picture focuses on labor, on industry, and on locality. It demonstrates a drive to document and pay homage to the kind of essential governmental service that we tend to take for granted. These factors all make for a work of art that is nothing if not honorable, especially in terms of what mattered to New Deal programs and the artists they supported.

But stillpainting a sewage station? That sense of regionalism, which had artists looking to the real world around them for subject matter (and presaged today’s interest in thinking/buying/acting locally), was encouraged by the New Deal and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The Federal art programs were administered through states so that each could create initiatives around its particular strengths. Here, for instance, a movement to create art centers throughout the state led to the transformation of the private Walker Museum into the Walker Art Center.

Beyond its particular programs, the striking (or scandalous) thing about the New Deal was that the Federal government actually paid people to be artists. It wasn’t necessarily a simple procedure, of course, and over the course of the Depression several programs were set up: the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) in 1933 and 1934; the Treasury Department Section of Painting and Sculpture, also in 1934; and finally the Federal Art Project, which lasted into the early 1940s. There was also a documentary photography program administered through the Farm Security Administration, which supported the creation of images that have become iconic, both aesthetically and historically.

It’s not surprising that many people thought New Deal art was a not-so-subtle sign of communist subversion within the U.S. government.

Just as it is now, government support for the arts was controversial back then, too. For one thing, Communist leaders in the Soviet Union had established Socialist Realism as their officially sanctioned artistic style, which was easily confused with the Social Realism movement in the U.S. and other countries. The Social Realists’ focus on labor and local subjects, moreover, may not have been overtly propagandistic, but it did mean that they and the Federal government shared certain ideals about labor and industry. So it’s not surprising that many people thought New Deal art was a not-so-subtle sign of communist subversion within the U.S. government.

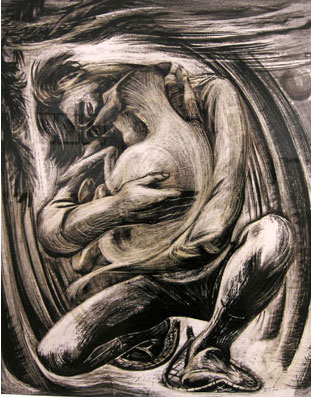

That said, New Deal programs funded plenty of art that fell outside the Social Realism camp, as By the People shows in its “Modernism and ‘The Project'” section. Plenty of artists were eager to experiment with abstract and surrealist styles that had originated in Europe, as evidenced by the number of works in this section with “construction” or “composition” in their titles. Cabbage, from 1937, even harks back to Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubist experiments from 20 years earlier. But the work in this gallery that provoked a smile was Difficulty of Thought, a surrealist fantasia by Shirley Julian that includes a figure whose head is mostly missing, as well as a flying-yet-tethered body. It’s the kind of work that exposes the kitsch inherent in Surrealism itself.

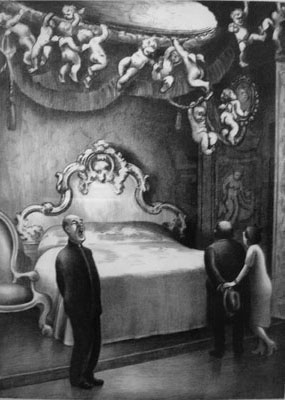

In an adjacent gallery devoted to “The Other Half: Women and the New Deal,” is Ballet Utopia, by Julia Thecla. This could easily have been placed among the other modernist works, but then there’s a fair amount of overlap among the works and the sections in the exhibition, overall. Thecla portrays two ballerinas on lofty, rocky points, the arms of one encircling one of the many clouds surrounding them. This piece prompted a grin because of its sheer whimsy and ultimate mystery (despite the dancers’ modestly-sized bosoms, it’s not hard to imagine this piece inspiring John Currin). Unlike Shirley Julian’s strained efforts to emulate the Surrealists, it’s clear that, in Ballet Utopia, Thecla was on her own trip.

By the People also includes a small section on photography that includes masters like Ben Shahn (better known for his paintings and works on paper), Berenice Abbott, and, as mentioned, Dorothea Lange. Lange’s wisely titled Hoe Culture says more about the stitching holding together a man’s clothing than it does about the tool he’s holding (whose handle is all that’s visible, anyway). There are also photos here of laborers standing in line and children living in a cardboard shack that are despairing in their immediacy.

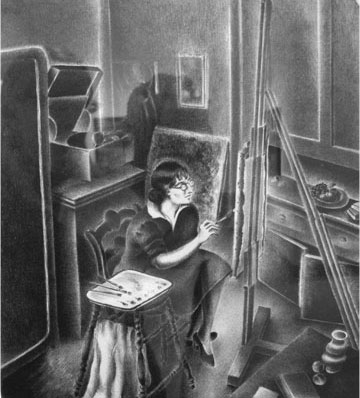

But I’d prefer to close out this survey by noting that fourth smile-provoking work, a print by Minnetta Good. It’s a self-portrait, titled Artist at Work, and the bespectacled Good shows herself in sensible pumps, sitting before her easel, which is wedged into her tiny Greenwich Village kitchen. According to U of MN art history professor Karal Ann Marling (who provides astute commentary on a number of works in the show), Good aimed to show art-making as a type of labor with as much validity as, say, timbering or steel-manufacturing; indeed, that’s why her work has been placed in the “Industry” section of By the People. And maybe that juxtapositionthe prim Miss Good sitting next to pictures of blast-furnaces and mills and oil tanksis part of what made me grin. But it was also the utter wholesomeness, earnestness, and idealism that emanate from this print, carefully labeled Federal Art Project/NYC/WPA in one corner. Good believed that art could make a difference in a time of dire need; it did, and it does.

About the author: Julie Caniglia is a freelance writer in Minneapolis and the former editor of The Rake magazine. In addition to The Rake, Caniglia’s arts writing has appeared in Artforum, Salon.com, Metropolis, I.D. Magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, and other publications.