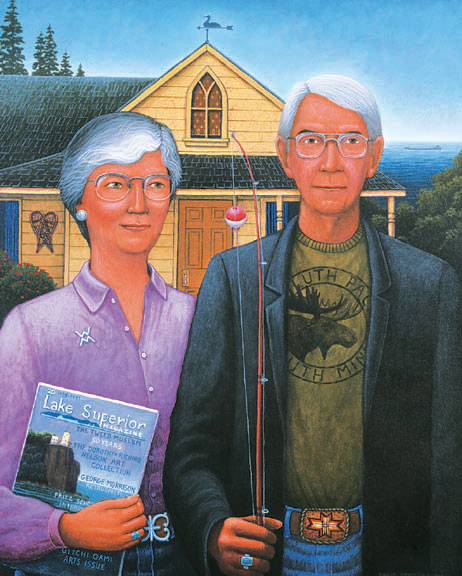

VISUAL ART: Birchbark Boxes, Bandolier Bags, and Modern Art

Ann Klefstad reflects on the new Nelson collection, a gift to the Tweed: artwork and craft by Native artists, from historic pieces to kitsch, side by side with work by lauded contemporary artists. She finds the whole thing an odd, but revelatory mix.

RICHARD AND DOROTHY NELSON BOUGHT A LITTLE BIRCHBARK box ornamented with porcupine quillsa traditionally made objectat Sault St. Marie in the 1950s. As decades passed, the charm infused into this object sought out its kin, and the Nelsons sought out other such things, beginning with basketry and eventually buying beaded bandolier bags, moccasins, dance regalia. The cultural life of American Indians in the Great Lakes region became their study, and they sought out Ojibwe, Iroquois, and Cree artifacts from dating from the 1850s on.

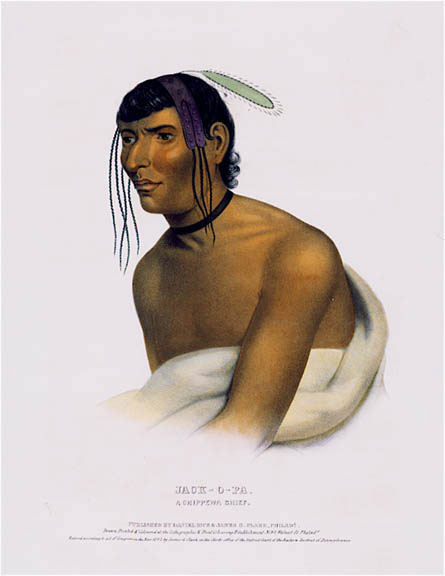

They added to the collection, old maps and paintings and prints by such artists as Eastman Johnson, who recorded Ojibwe life on Madeleine Island and in Minnesota in the early nineteenth century.

Their most recent pursuit has been the work of current Native artists such as George Morrison, Patrick DesJarlait, David Bradley, and Frank Big Bear.

This show at the Tweed Museum of Art (on the UMD campus in Duluth) celebrates the gift of this collection to the museum. Not all of the work from the collection is displayed, but the choices on view are representative: objects made for use, like winnowing baskets and syrup-stirring spoons; crafts made for the tourist trade, like birchbark dollhouse furniture; beaded regalia and finery; and paintings. The Nelson collections home in the museum is a large floor-to-ceiling vitrine, and all categories of the collection are presented together.

Seeing a carved syrup-stirring stick next to a David Bradley painting in a case is odd, but weirdly revelatory. The difficulty that Native artists have had in escaping the natural history museum, the anthropologizing of their work, hovers over this presentation. How do we see art produced by contemporary artists who are part of two traditions? As artists involved in the long and ongoing conversation of the art world? Or as interesting others, whose difference from the mainstream constitutes their value? Quaint Indians, so to speak?

Theres a toxic legacy to this association of traditional craft objects with Native artists work, but in this particular moment theres an opportunity revealed by it as well: a way for art to refind its cultural relevance.

Duck-Headed Spoon and Bandolier Bag

A large wooden spoon with a duck head carved on the end of its handle is a sculpture and a useful thing, too. Theres both discretion and power in this pretty, simple thing. Its an object charged with significance by means of the carving, the figuration, the design. Thats what designers do, and design is increasingly inflecting the artworld, creating hybrid objects that have designs relation to function but arts mad desire to be possessed by spirit and idea. As artists seek relevant roles in the daily life of the culture (think Marcus Youngs attempts to get art into daily life in St. Paul, or artists uses of spectacle to drive green thinking, or to influence politics), the way aesthetic power has been used in Native cultures becomes something of vital interest.

The bandolier bags, beaded shirts, wristlets, and other dance or ceremony regalia in the collection stir other thoughts. These royal garments announce status, but its not status granted by any aristocratic system. Status is created here by claiming the power to create a self through ones own skill and audacity. In the coming tough times, this kind of do-it-yourself ethos gets very interesting.

Audacious and courageous self-creation is part of the Western tradition of artmaking, as well as part of the Native tradition. Its one of several points of conjunction of the two. Frank Big Bears work, shown in the next gallery in the Tweed, bears this out.

About the author: After being a lot of things, Ann Klefstad is once again, in Duluth, simply herself.

What: Selections from the Richard E. and Dorothy Rawlings Nelson Collection of American Indian Art

Where: Tweed Museum of Art, University of Minnesota-Duluth, MN

When: Ongoing as part of the permanent collection

Admission is FREE and open to the public