Abstract Hepcat

The sheer scope and variety of George Morrison's body of work - intimate paintings and monumental sculptures, pen-and-ink drawing, wooden collage - speaks to intellectual and aesthetic openness wedded to a deep commitment to technique and craft.

The pieces I most closely associated with George Morrison before seeing this exhibition were his later sculptures ― in particular his monumental wood collages and obelisks. So, the variety of works included in Modern Spirit: The Art of George Morrison came as something of a revelation to me. Morrison’s willingness to experiment is on display, but so is a certain painstaking attention to minutiae. The total impression is of an intellectual and aesthetic openness wedded to a deep commitment to technique and craft.

The Minnesota History Center is the last stop for this excellent retrospective, a joint project of Arts Midwest and the Minnesota Museum of American Art (MMAA). (Many of the works on display are in the permanent collection of the MMAA.) Visitors―particularly those who, like me, were previously uninitiated into the breadth of Morrison’s artistic interests ― will appreciate the wall text, which combines sensitive observations about individual pieces with biographical material. For additional background, viewers may be interested in reading Turning the Feather Around: My Life in Art, a valuable collection of reminiscences culled from interviews conducted with Morrison and his former wife (artist and educator Hazel Belvo) by Twin Cities-based writer, Margot Fortunato Galt (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1998). In Turning the Feather Around, Morrison emerges as a congenial, accessible guide ― not just to his own work but to the Abstract Expressionist movement of which he was a part and the New York City arts scene that gave rise to it.

Modern Spirit isn’t a show to breeze through quickly; your visit will be shortchanged if you set aside anything less than a couple of hours to tour Morrison’s large body of work. The drawback to this ample display is that the exhibition has, of necessity, been mounted in a series of cavernous, gloomy rooms. The space easily accommodates Morrison’s towering Red Totem I (1977), as well as several single-bed-sized wood collages, and lighting is, of course, kept low to preserve the artwork. All of this is understandable. Nevertheless, the experience of seeing the work here is a little like strolling through an airplane hangar.

George Morrison, Whalebone, 1948, oil on canvas, 25 x 24 3/4 in. Coll. Kevin and Kathy Kirvida

A couple of early realist paintings give way to works with a distinct Cubist flavor. Morrison moved to New York City in 1943, where he attended the Art Students League and rapidly developed a self-assured idiom that suggests the influence of Picasso and Braque. Whalebone (1948 ) ― a still life in which the white mass of a whale vertebra dwarfs a wine bottle placed next to it ― is one such Cubist-influenced piece, although the way in which Morrison fits together fields of color to shape these and other, more mysterious objects in the foreground and background begins to feel very much his own.

From the same period, Dawn and Sea (c. 1948) is formed of Fauvist chunks of red, orange and yellow sky and a darker patchwork of hills and sea. Here the artist has hit on a strategy he will return to throughout his career: using the landscape as an excuse to treat the medium and materials as subjects in their own right. Speaking about some of his later works, Morrison says that “the phenomenon of paint was what the painting was really about. Rather than getting sentimentally involved with a subject, the artist was more conscious of the paint itself, and that became the painting.” The title of Painting #12 (Pacific) (1952) suggests that even at this early stage in his career, the landscape in question is but the back door through which Morrison accesses his primary concerns: texture, color, technique, the properties of the paint itself. Scumbling reveals a second layer of color under paint so thick that the piece looks wooly ― gray, white, red and brown shapes seem as if knitted together.

George Morrison, Painting #12 (Pacific), 1952, oil on wood board, 27 3/16 x 33 1/2 in. Seattle Art Museum

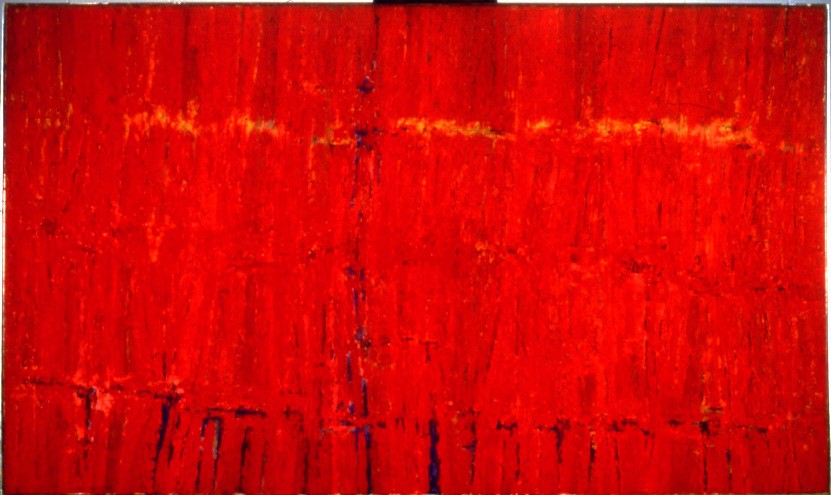

George Morrison, Red Painting (Franz Kline Painting), about 1960, oil on canvas, 47 x 79 in. Coll. Gerald and Dorit Paul

George Morrison, Red Painting (Franz Kline Painting), about 1960, oil on canvas, 47 x 79 in. Coll. Gerald and Dorit Paul

Even after Morrison has all but abandoned pictorial subject matter, however, the ghost of a horizon haunts many of his abstract works. Red Painting (Franz Kline Painting) (c. 1960) is a gorgeous field of red through which twinned blue and yellow horizon lines seem to leach. The dominant red portion of the painting is not an undifferentiated mass, but rather composed of vertical blocks of color, like bricks standing on their short ends. It’s a banquet of primary colors spread on a canvas measuring more than three feet by six feet; there’s nothing else quite like it in the show.

In fact, the retrospective includes a number of one-offs that similarly fall outside the more clearly defined periods in Morrison’s oeuvre. An untitled black-and-white drawing from 1945, for example, could be mistaken for a Miro, with its spindly shapes that hang together like a mobile. An untitled 1957 work in tempera on paper is another outlier; here, pastel colors are so lightly applied that the weave of the paper shows through, in contrast to his other works from the same period where the paint is as thick as frosting. See also a cluster of small works from the late 1970s and early 1980s: Red Rock Variation, A Memory for Franz: Kline Fragment (1978) is a paper collage incorporating a reproduction of one of Kline’s paintings (the two artists were close friends); next to it, Brown and Black Textured Squares (1982) is a delicate chessboard of crosshatching that seems to melt and warp. Grouped with these is Propylon: D’Arcangelo Fragment (1982). A cursory glance interprets the work as an abstract composition in gray, blue, fuschia and black, but on closer inspection, the image resolves into a slice of overpass supported by an off-kilter concrete pier and traversed by power lines. “That looks like 35-dub,” a fellow visitor quipped to her companion.

George Morrison, Construction, 1953, gouache on paper, 17 1/2 x 23 1/2 in. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

George Morrison, Jive Samba, 1955, ink on paper, 17 1/2 x 22 5/8 in. Collection Minnesota Museum of American Art.

The presentation of these three small works is one of several thoughtful juxtapositions put together by the curator, W. Jackson Rushing III, Adkins Presidential Professor of Art History and Mary Lou Milner Carver Chair in Native American Art at the University of Oklahoma. (Rushing and MMAA executive director Kristin Makholm coauthored the catalogue of the exhibition, which won a Minnesota Book Award in 2014 and also features an introduction by the artist Kay WalkingStick.) Others include the hanging of Construction (1953) ― a bright gouache in which red lines subdivide patches of white and orange like highways on a wintry map–alongside Jive Samba (1955), in which angular black shapes dance across white paper and gray rivers of crosshatching. The negative spaces between what the wall text calls “abstracted hepcats” (surely history’s first use of this delightful phrase) are as vibrant as the hepcats themselves.

In addition to showcasing his mastery of many modes and techniques, Modern Spirit also demonstrates how well Morrison’s ideas translate between formats and media. For him, the wood collages were “paintings in wood” in which “the grain of the wood and the knots suggested the movement of clouds, sun, and wind. And below the horizon line, the rough water or beach,” Morrison explains in Turning the Feather Around. A large, untitled wood collage from 1975 hangs at the entrance to Modern Spirit. It flows left to right like a river, with long slopes that lead the eye up and to the right, only to halt at an outcropping of vertical chunks. Particularly lovely are areas where round or curved pieces of wood seem to have gathered little fragments around them, like leaves turning in an eddy. Here and there, faded yellow and blue paint and orange stain on a treated two-by-four stand out amid weathered grays. These colors are delicious, like lone yellow and blue M&Ms in a bowl of brown ones. Half worn away, they show that vibrancy, like anything else, is a matter of context.

The exhibition also includes lithographs that Morrison made from rubbings of his wood collages, a neat innovation allowing for easier reproduction of these exceedingly time-consuming pieces. It is surprising how well the wood collages, with their variations in color, depth and texture, cross over into a two-dimensional, monochromatic format. Similarly, Red Cube (1983), a lithograph, prefigures Cube (1988), a sculpture constructed from writhing wooden pieces that come together, impossibly, at right angles. In contrast to the driftwood collages, Cube is made from exotic woods chosen for their rich colors and carefully carved, sanded and polished.

Red Totem I (1977) is a giant pillar seemingly constructed, like a game of Jenga, out of solid wooden blocks. Circle the sculpture, though, and you watch as blocks that appeared thick and broad on one of the pillar’s faces become the slender edge of the next. The sculpture is hollow; the wooden pieces are fixed to a plywood core. Morrison points out in Turning the Feather Around that, if they were solid, his totems would be incredibly heavy. Nearby, a small totem in bronze is on display in a glass case. This untitled piece, dating from 1988, reinforces how readily Morrison’s works can be adapted to different materials, and in this case, to a drastically different size.

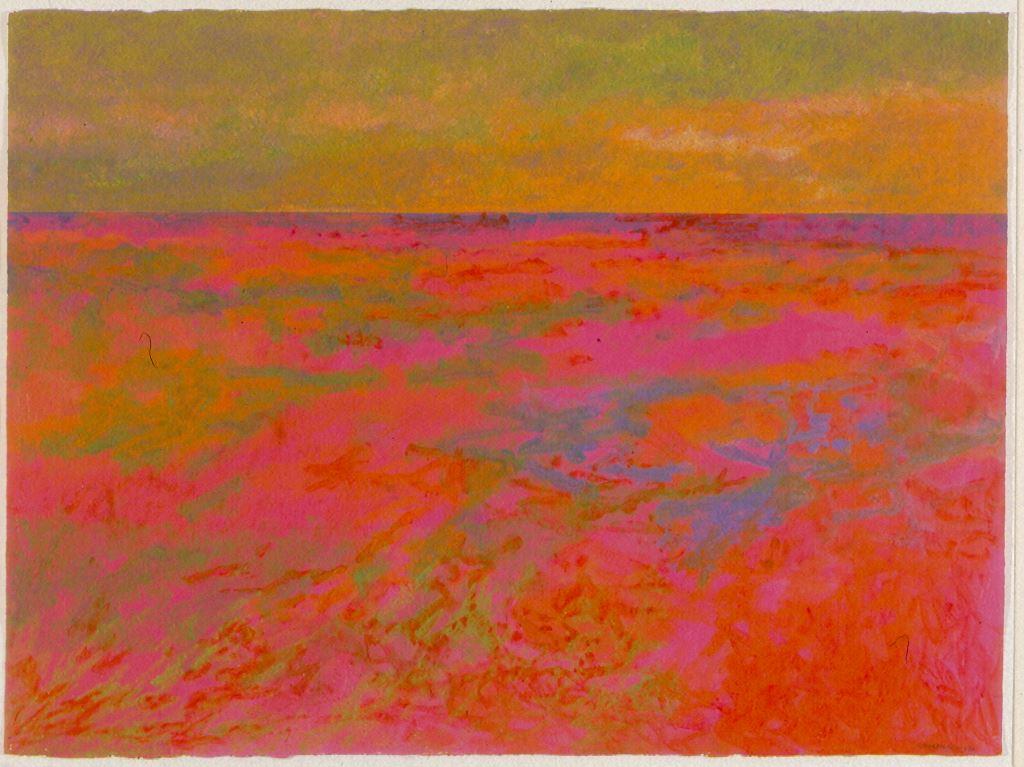

George Morrison, Spirit Path, New Day, Red Rock Variation: Lake Superior Landscape, 1990, acrylic and pastel on paper, 22. × 301⁄8 in. Collection Minnesota Museum of American Art.

Morrison’s wood collages and sculptures suggest a boundless patience that is also evident in the abstract pen and ink drawings included in the show ― particularly in untitled drawings from 1973 and 1977. In conversation with Galt, Morrison refers to a lifelong habit of doodling, and these large drawings, composed of faint, tightly spaced parallel lines, look like what might happen to a doodle if you gave yourself over to it for days. From a distance, the drawings appear as soft, hairy masses; draw near and they are more like explosions of wooden splinters. Suggestions of layers create a sense of depth, and there are even traces of a horizon line. The drawings are mesmerizing, like handcrafted, monochromatic versions of those Magic Eye posters that were ubiquitous in the early ’90s.

The exhibition closes with an extensive series of paintings of Lake Superior done at Red Rock, Morrison’s studio on the Grand Portage Reservation. The landscapes (lakescapes?) start small, because Morrison was suffering from a serious illness when he began them; over time, these works grow larger and more lush. The paintings vary in intensity of color but not in format: all feature a horizon line that divides the sky from the lake three quarters of the way up the painting. It’s hard to argue with the sheer pleasure afforded by these pieces, although with their pastel palette and repetition they slightly resemble that most commercialized body of work, Monet’s Water Lilies. Let’s hope that a proliferation of tote bags and umbrellas decorated with Morrison’s Lake Superior is never allowed to wear out this series’ appeal. It would be a shame for familiarity to blunt the startling beauty of his work.

Related exhibition information:

Modern Spirit: The Art of George Morrison is on view at the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul from February 14 to April 26, 2015. The Minnesota Book Award-winning exhibition catalogue by the same name is available to order online and in bookstores around the region.

Hannah Dentinger writes about visual art, literature, and sometimes both at the same time, a habit she developed while doing graduate work on the Anglo-Welsh poet and artist David Jones. She considers herself a semi-professional appreciator of the arts.