VISUAL ART: Assessing the 2008 MCAD/Jerome Fellows Show

Critic and artist Ann Klefstad reflects on the fruits of this year's crop of Jerome Fellowships--she's decided that the money awarded to each in this diverse group of artists was money well spent.

A GATEWAY TO ARTISTIC REPUTATION, the annual Jerome Fellowship selects five Minnesota artists whose work shows promise to receive $9,500 to make art for a year. Then we get to see the results. The knowledge that much has been given means that much is expected; the squawk, Ten grand for that!? is often heard after Jerome openings.

But this years crop delivers value. The works as diverse as the artworld is nowadays. Its a notable feature of the current show that each artist is doing something utterly different from the others. Book design, landscape photography, research, sociological exploration, and wish-fulfillment fiction all bloom as appropriate actions for artists.

The Artists

Entering the gallery, at first you see two very different works: one, a gorgeous flying creature with a proliferating head, colorful, playfully dangerous. Two, a couple of thick books lying on a stand.

Liz Millers dragon/bird thing flies through the space, spewing hearts and teeth, as richly complex and colorful as her work always is. This work is about pleasure, and also, maybe, in these times, about mistrusting pleasure, looking for its dangers. Its a fiction, a dream of a beast that, in the light of morning, becomes the pile of clothes on a chair. Millers work strikes me as brave in that she insists on the relevance and importance of virtuoso beauty and play as ends in themselves. In a self-serious artworld, that takes guts.

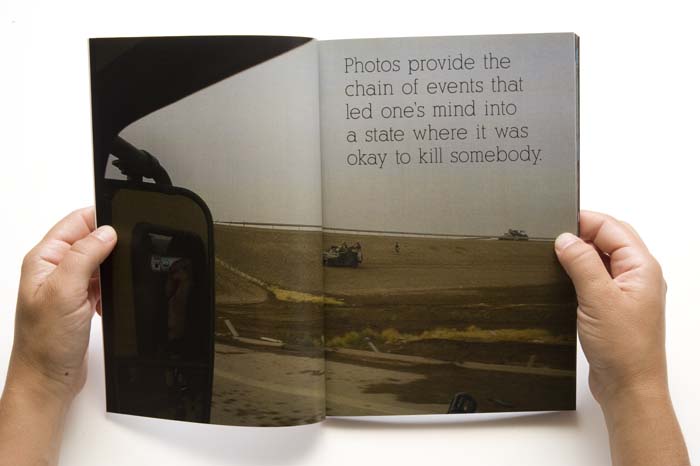

The books? Also brave, and with no end in sight for the need for courage. Its actually a few copies of the same book, a prototype for a bound collection of a thousand or so photos and a few crucial and beautifully chosen/written pages of text. Monica Hallers friend Riley Sharbonno was a nurse at Abu Ghraib, and he took over a thousand photographs there; many of them, individually, are seemingly inconsequential as visual documents, but all together they’re potent, collectively tied to otherwise ungraspable memory. Hallers conversations with Sharbonno, and his commentary on the images, are interspersed with black and white pages in a rhythm that uncannily gives to the viewer the sensations of struggling to remember, and to forget, the place the photos capture. Not incidentally, the books a brick of incontrovertible fact, on which we, the audience, are expected to act. This is not a book, writes the artist, in maybe unwitting reference to the way books almost always reject their book-nature in favor of something else. This is an object of deployment.

It seems to me that of Colin Kopps photos its the landscapes, the settings, the cars, the light, that are his true métier. The two portraits in the mix are less convincing. Frankly, in this city at least, the large-scale color portrait of a subject in an atmospheric setting whose face has drained and opened as a result of the rigors of the shoot belongs to Alec Soth. But the other ones, the cars, fireworks, houses? They belong to Kopp. Sinking House has a subtle, simple three-color palette and a resonating timeless presence that could place it among Sung paintings, if it wasnt so firmly Kopps and his alone. And The Malibuno ones ever done more with grey, and this is a color photo.

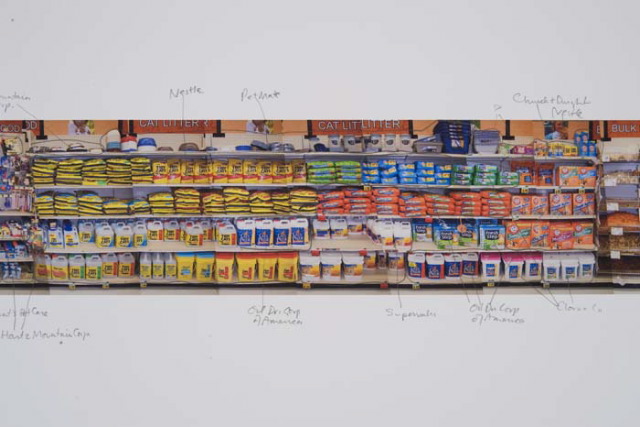

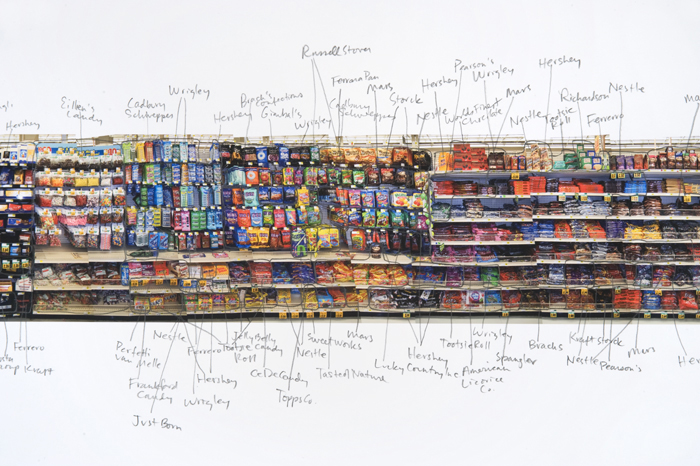

Rosemary Williams obsessive document of the entire (nonperishable) contents of a Cub Foods store evokes Ed Ruschas documents of L.A. streets. It enlivens all those relentlessly attention-getting labelscans and boxes as domestic architecture. Its weirdly personal for me because I have open shelving in my kitchen so all the labels are visible: I like them, all that invention and color lavished on these cheap boxes and cans. I used to buy Russian canned veg at the La Brea Bargain Circus because the labels were so fantastic. But the demanding nature of that packaging can drive some people crazyit was one aspect among many in my house that irritated a dear friend of mine to apoplexy. It seems that Williams is playing on both aspects of the designed life, in a scientific deadpan mode. Even the superlarge sheets of thick white paper displaying the hyperminiaturized array have that doubleness, the dialectic formally at play.

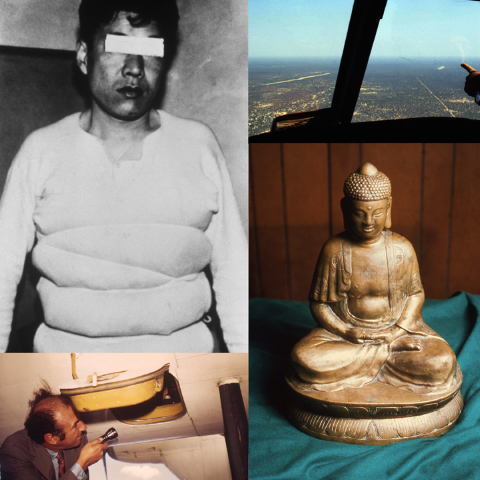

Matt Bakkoms work is the hardest to love but may be, in the end, the most fruitful avenue of all. Hes an archivonaut, a diver into the records. His project here is a collection of photos of devices and shifts used to conceal drugs, which he found in a federal archive. But hes done many other archive-based works. Its a Fluxus-type art-into-life project, a way to take the no-holds-barred boundary-crossing curiosity that artists have always needed and exert it on the world of fact and history. In an era of official lies, great and small, when any political utterance and all ads and pitches and a hell of a lot of other communications as well are assumed to be made of solid bullshit, an artists license to dig, explore, inquire, and show can be a damn good thing. The weird pathos of some of the shots is just sprinkles on the doughnut.

Whats an Artist Nowadays?

What an artist does is increasingly mysterious. For some (see Michael Fallons recent article on his departure from the art world) this is despairing: arts a category that seems irrelevant and outworn in a do-it-yourself media world. But the artists in this show at least point to cultural functions that people trained as artists can perform. Does this sound feeble? Maybe a little.

The category artist has, over the last two centuries, meant something like the person who makes cake, eats it with appetite, generously gives it to beggars, bravely flings it at the cake-purchasers, and lives to tell the tale. Mostly. The artist has been the person who escapes the iron laws of class, who flouts the idea that you are your income. Thats one reason why the role has been so appealing. Its one of the few windows through which we can get a view of what freedom might look like, a freedom that is receding into a misty distance now, in this era of brutal economic disparities and skyrocketing educational costs.

But maybe in this show the persistence of creativity can show ways in which artists are still relevant to the culture, even when theyre doing things that fall outside of the usual art rubric. When art becomes simply making the thing that cries out to be made, saying the thing that cries out to be said, it re-enters the world, not as a ticket to fuck-you gestures, but as a citizen. Sounds a little dull? Less dull than last years fashionable stances.

About the author: After being a lot of things, Ann Klefstad is once again, in Duluth, simply herself.

What: 2008 MCAD/Jerome Foundation Fellows Exhibition

Where: Minneapolis College of Art and Design Galleries, Minneapolis, MN

When: Exhibition runs through November 12, 2008

Admission is FREE and open to the public