The Kingdom of Nah

Matt Konrad explores Lester B. Morrison's edges-of-everything world, as captured in Little Brown Mushroom's "House of Coates," written by Brad Zellar and photographer Alec Soth and just released in trade paperback by Coffee House Press.

Note: This essay was originally published in 2012, on the publication of Little Brown Mushroom’s limited-edition series of the book. The title has just been published in trade paperback form for wide release by Coffee House Press.

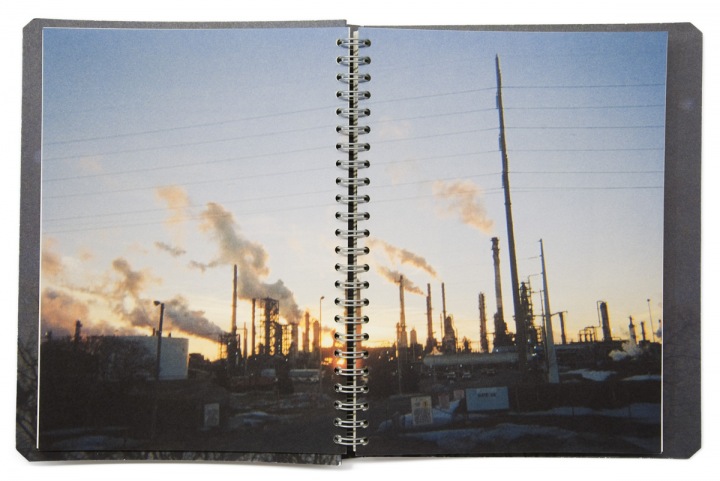

The first time I ever saw the Pine Bend Refinery lurking off the shoulder of Highway 55, south of the Twin Cities, it was one of the most unsettling experiences of my life. I was 21 or 22, driving from Minneapolis to an unfamiliar corner of the exurbs, heading for poker and beer with a couple of friends who shared an apartment down that way. It was the first summer since I’d moved here from South Dakota that I had a car of my own, and my previous mental map of the metro — mostly Minneapolis, with the occasional suburban pushpin where acquaintances lived or parties were thrown — was expanding as a result. But here, I was out of my element. I’d never driven myself out of town this way. I have a lousy-at-best sense of direction, and the summer twilight was rapidly fading as I came to the increasingly unavoidable conclusion that I was lost.

As the dark encroached and I tried to find my way back to anything resembling familiarity, I saw light in my peripheral vision that seemed to come from nowhere. The sourceless glow looked vaguely sinister, but I was lost, and pointed my car at it anyway. And then I nearly drove off the road at the sight of a massive oil refinery I hadn’t known was there, looking for all the world like a mammoth, forgotten set from Blade Runner, lit with string after string of bulbs giving off a daytime glow. I was already lost, but for a moment or two I felt like I’d disappeared into a parallel universe as well.

There’s a two-page photo of the refinery toward the beginning of House of Coates, the recently published art-and-story production from St. Paul’s Little Brown Mushroom Books; while the image replaces my summer evening with what looks to be an achingly cold, clear winter sunrise, it nonetheless inspired a flash of that same unsettled feeling when I turned to the page. And it couldn’t be more appropriate; House of Coates is deeply concerned with life on the edges, with men displaced from the world, and with the corners in which, like an unknown refinery, they manage to hide in plain sight.

The air of mystery around House of Coates is pervasive both within its pages and without. Inside, the book sketches one winter in the life of drifter Lester B. Morrison, who author Brad Zellar tells us “seemed to have been born with what the Portuguese call saudade, a sort of eternal, metaphysical homesickness.” The book’s copious photos are also credited to Lester B. Morrison, and that’s where the mystery jumps off the page a bit.

See, the Little Brown Mushroom publishing company, which produced House of Coates, is operated by Minnesota photographer Alec Soth, renowned for his evocative portraits of the Midwest’s fringes and loners and unnoticed details; Lester’s disposable-camera photos, while frequently ill-lit and mis-focused, capture much of the same strange, sad beauty. And one “Lester B. Morrison” happens to share his initials with one “Little Brown Mushroom” — and with the zine Lester Becomes Me and three other LBM publications for which he’s credited as author. Soth and Zellar have both remained poker-faced while asserting that Lester is a real person and a frequent collaborator. Whether he’s person, character or something in between, he’s a fascinating figure.

Besides, as House of Coates makes clear, Lester B. Morrison has bigger existential fish to fry than all that. Lester is the quintessential loner. Since boyhood, he has felt a powerful draw to retreat from the world. He’s thoughtful, observant, even mordantly funny sometimes — Zellar writes that “he didn’t seem to fit any of the obvious pathologies of a man running from the world and responsibility” — but he has spent his life fitting in exactly nowhere. Which is why he’s drawn to the world around that very refinery — in his words, “The Kingdom of Nah.” It’s a place where nothing seems permanent, and where a guy like Lester can sleep in a motel parking lot if he doesn’t feel like renting a room.

And the book is really as much about the place as it is about Lester. Visitors like me may drive through and find this edge-of-everything world alien, but that makes it all the more likely that someone like Lester will find something resembling home there. He’s left alone, orbiting mostly men who are mirrors of himself, and both story and photos describe a connection among them that’s almost spiritual.

______________________________________________________

“The Kingdom of Nah” is an edge-of-everything place where nothing seems permanent, and where a guy like Lester can sleep in a motel parking lot if he doesn’t feel like renting a room.

______________________________________________________

The photos, along with Hans Seeger’s lovely design, would be reason enough to find yourself a copy of House of Coates to get lost in, by the way. They purport to be pulled from Lester’s endless supply of truck-stop disposable cameras, and they feature plenty of the unexpected, voyeuristic thrills that come from digging through a found shoebox of someone else’s snapshots. (Just to make things extra-meta, there are two shots of a bureau: one drawer is full of disposable cameras and another with years’ worth of intimate Polaroids.)

Coincidentally or not, Lester shares with Soth an eye for the distinctiveness and raw, unusual flashes of loveliness that a careful observer can find in this part of the country. Midwestern visual themes emerge throughout: as any Minnesotan would expect, there are plenty of run-down ramblers, cheap paneled walls and acres and acres and and acres of dingy snow. And these themes coupled with the photos’ flat quality and sparse color palette bring the unusual moments of beauty — the neon sign at the House of Coates bar, a big empty sky at sunrise, a weirdly evocative empty coat rack — into stark relief.

As befits a loner of Lester’s dedication, there aren’t a lot people evident in his pictures. When they are, they’re distant figures or photos-of-photos or thumbs intruding on the lens — just enough to remind you of the humanity in this no-man’s-land. Even for Lester, that humanity can’t be entirely avoided, — indeed, it’s a chance human connection that serves as the fulcrum for the story. Lester spends a fair amount of time at the “lonely man magnet” known as the Travel Plaza truck stop; he “would contend that the Travel Plaza was as inspired and visually arresting as any museum installation in America. Every time he went in there he found something that almost made him feel as if he was living in an age of wonders.”

And, awash in this wonder, Lester strikes up a conversation that gets him thinking about the meanings of staying put, the potential of making a connection, and the possibility of finding something like a moment of grace. It’s a satisfying destination for a remarkably engaging journey (especially considering the raw materials are ostensibly a quiet loner, a scrubby stretch of exurban highway, and a shoebox full of snapshots).

And House of Coates has struck a chord: Zellar and Soth’s launch event (at St. Paul’s Midwest Hotel, an urban outpost of the Kingdom of Nah) drew a sizable crowd, and the book’s first printing of 1,000 quickly sold out. You can still pick up a copy from the book’s second edition, though, and I’d recommend you do so; this is a truly, deeply Minnesotan story, and one well worth spending some time with.

Related links and information:

House of Coates, by Brad Zellar with photos by Lester B. Morrison, designed by Hans Seeger, was first published by Little Brown Mushroom Books in March 2012, in a limited edition of 1000 spiral-bound copies. A new trade paperback edition of the title is out, as of October 2014, from Coffee House Press.

Matt Konrad writes, builds websites and mixes drinks in Minneapolis.