Why Is It So Difficult to Talk Critically About Socially Engaged Art?

Definitions of terms for work loosely designated as "social practice" is contentious business. Critical review of the diverse range of work in this field is even more slippery. So, how can we begin to carve out a space for serious evaluation and analysis?

Why is it so hard to talk critically about socially engaged art? One of the immediate challenges of reviewing the Nash Gallery’s group exhibition, thinking making living, or any show that presents such work for that matter, is that the included works defy the conventions of language and aesthetic judgement of artistic practice that I’ve learned over the years. Every conference, every conversation related to social practice I’ve been part of has stumbled over how to even define this work. All of which makes the process of its analysis slippery, interesting, and sometimes aggravating business — much like the acts of thinking, making, and living. In order to place some stake in the ground, I should declare my own presumptions: I think of socially engaged art (which I’ll interchangeably call “social practice”) as work that is co-created by an artist or organization with other people. It’s by nature participatory and often aspires to social or political change that pushes against established hierarchical power structures.

But how do you evaluate these practices?

Deborah Fisher, executive director of A Blade of Grass, an organization which funds socially engaged art practices, eloquently outlined here the struggles that artists themselves have with identifying the aesthetic criteria for their work.

Some say the aesthetics are in the things you can see—the things that look like art products. Others place aesthetics in the ethics and the qualities of the interactions. Others place aesthetics in the elegance of the overall idea. Others in the relevance and value of the project to the community.

As for herself, she says:

The artists I am most interested in are actively evolving their practice beyond institutional critique, and are instead proposing how power, agency, interdependency, and authority might be redistributed, repurposed, perforated, torqued, and even taken apart and creatively built anew.

To my mind, all of these things are at play as I try to understand and evaluate social practice. I’m certainly drawn to a project that is visually compelling and centered around a well-crafted idea. I appreciate it when the rules of engagement thoughtfully consider the participant’s experience, when I feel less like a manipulated test dummy and more like I’m in it, together, with the artist. And when an artist’s practice shifts an established power dynamic to create opportunities that might not have previously existed — whether it be for a community, an organization, or an environment — that zeal is infectious, and I want to engage. As a viewer/participant of this sort of work, I like the appeal for direct investment, that I’m learning all the time, always trying to wrap my head around what constitutes “good” participation.

While socially engaged artistic practices are not new, there is definitely a resurgent interest in this work evident in the growing number of artists, academic programs, conferences, exhibitions, and scholarship devoted to its examination. As artist J. Morgan Puett of Mildred’s Lane noted in her recent lecture at the Regis Center for Art, “this work is not new, there’s just a new reaction to it.” But why? Socially engaged practice is often framed as an alternative to an elitist, exclusionary, and capitalist art world. But the more institutionalized and professionalized social practice becomes (in predominantly wealthy, white institutions, I might add), the more I see a hierarchy emerging that separates social practice knowledge-authorities and those working on the outside. That growing divide raises an important question: Does social practice belong in art museums at all?

I’d argue against easy answers. Knowledge is power, and it’s exciting to see that power used by artists to outwit the very systems of oppression, the -isms, that have too long held sway — racism, sexism, classism, ecological terrorism, or capitalism. Take Theaster Gates. While his work isn’t featured in the Nash exhibition, Gates recently made an appearance at the Walker Art Center, where his project See, Sit, Sup, Sip, Sing: Holding Court—a long table surrounded by chairs and chalkboards designed for visitors, museum staff and guests to have open dialogue—is nestled within the exhibition Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art. Gates is a charismatic (to put it mildly) art star, well-known within the social practice sphere and beyond for work like Dorchester Projects, a series of reclaimed abandoned buildings in Chicago’s South Side that were made-again with repurposed materials and now serve as a multi-functional, cultural space and model for neighborhood revitalization and socio economic renewal. Dorchester Projects, like other impactful examples of socially engaged art, isn’t just a one-off; it embodies a lasting commitment to the surrounding community. And in this field, it’s not the quick sprint but the enduring journey that seems to make real inroads to social change.

When this sort of work happens in a gallery or museum, that ethos pushes back on how the institution traditionally operates. It’s one thing to have an exhibition that behaves rather conventionally — that is, where visitors see a collection of objects — but when an artist chooses to do a live, durational project in the gallery space, it requires an entirely different allocation of resources, new operating structures. For example, Fritz Haeg literally camped out in one of the Walker’s galleries for a month last year, inviting visitors to make themselves at home with him on a giant crocheted rug. Passersby could take off their shoes, drink tea, and do homey things, like knit or read. When Haeg’s month-long residency in the gallery was over, the Walker needed to hire a team of gallery tenders to host the exhibition space and authentically engage with visitors for the remaining months of the project.

Fritz Haeg installation at the Walker Art Center in 2013. Photo: Gene Pittman

Holding Court with Coco Fusco around Theaster Gates’s table installed in Radical Presence at the Walker Art Center. Photo: Gene Pittman

Christine Baeumler, Table Top Bog. Photo by the author

Edible Insect Tasting in progress at the Hydroponic Table. Photo: Christine Baeumler.

In thinking making living there has been a similarly strong commitment to enlivening the Nash Gallery spaces by hosting projects that invite visitor participation over the entire three-month run of the exhibition. It has undoubtedly been an exhausting endeavor on the part of the curators and artists, but without these moments of live interaction, thinking making living would lose the very social aspect so integral to this kind of work. Amanda Lovelee’s Elevated Structure for Elevated Thought and Crescent Collective’s (Laura Bigger, Artemis Ettsen, and Teréz Iacovino) Hydroponic Table are both physical structures that invite participation: Lovelee’s made a small wooden clubhouse designed as an intimate space for conversation, and Crescent Collective has set up a dining table and benches inset with hydroponic plants illuminated by grow lights. Both projects are familiar-looking structures—it’s easy enough to imagine the kinds of activities that might happen there without actually enacting them. However, it was only when I engaged in these projects with other people in the space, witnessed them animated by active use, that I felt like I had a true understanding of the artist’s intentions.

During the opening, Lovelee, a natural convener and people-person, sat in her hangout den casually chatting with others who cared to join her; she welcomed all comers to write a question onto a wooden Jenga piece that could serve as a prompt for dialogue between other visitors. A sign-up sheet hangs outside the door to her clubhouse allowing anyone to reserve the space. Similarly, an iPad is nested by the Hydroponic Table by which you may reserve the work’s curious-looking dining set, ideally suited for a conversation about sustainable ways to grow your own food. Artist Kate Casanova hosted her Edible Insect Tasting at that very table on the evening of the show’s opening — an apt metaphor for how to stomach new ideas for feeding our growing population. In fact, this corner of the gallery was completely abuzz that night in a way that felt familial, as if the assorted visitors weren’t in a gallery at all but at a family gathering, playing the sorts of games that bring generations together. And these kinds of shared, lived experiences between strangers or friends, even if temporary, are a pretty remarkable thing in the digital age.

When I returned to the exhibition, weeks later, on a weekday afternoon, the space was unsurprisingly empty of other gallery-goers. The projects mentioned above, once full of life, were quiet. The stillness afforded a better opportunity to look more closely at these pieces (as well as all the other works in the show) and to take note of how resourcefully and elegantly these artists married form and function through the use of reclaimed materials. I could appreciate the thoughtfulness and craftsmanship but, honestly I missed the people and the activity that had so animated the work before.

That same afternoon, I had planned my visit so I could partake in Jan Estep’s Conversation Series, a project she has staged at other locations, like the Weisman Art Museum and the Soap Factory. I’d prepared myself for something like therapy, and I was ready, or so I thought, to answer whatever questions Estep had in store for me. Seated side by side — Estep with a typewriter, paper pad and pencil at the ready — she began with the question: “What three words would you use to describe yourself?” After the conversation/interview, she requested 10 minutes alone to type up her notes. I was given the original, and she retained a copy for her archive and to display on the gallery wall. This simple act of having someone listen to me intently, then regurgitate my words back to me in such a poetic way was unexpectedly satisfying. When I read it, I had this funny realization that I actually should listen to myself more.

I had another one-on-one interaction on that same visit with dancer Dolo McComb, who is a collaborator with BodyCartography Project, a Minneapolis-based choreography/dance confab who were resident artists in thinking making living from late October to mid-November. The afternoon I visited, BodyCartography was rehearsing their piece closer, which is best described as:

a practice in being present. It is a performance intervention for two strangers (audience and performer) in public space that evolves into a communal experience. It is an invitation for engagement and empathy. Together we will examine how the space of connection between performer and audience can function as a site for transformation. closer lays bare the power of live performance to facilitate a re-enchantment of physicality and presence.

For 10 minutes, I followed McComb as she moved throughout the spaces of the Nash Gallery, trying to keep a safe distance, not knowing what to expect. What began as a slightly uncomfortable, self-conscious experience became something like an intimate wordless conversation. At one, transformative moment, McComb was standing right against me, shoulder to shoulder; our breath slowly synchronized, and I felt a great empathy for this woman I’ve never met. I also had an increased awareness of the space surrounding us, particularly when McComb was stretched out on the cold lobby floor while I sat on a bench nearby.

These live encounters represent the social and more performative qualities of socially engaged art, however many artists in the show created participatory works for which their presence wasn’t required in the gallery. Rebecca Krinke’s Library of Touch, a series of handmade books whose titles include Burned, Skin, Body, Fodder, and Bedding invites viewers to physically touch and flip through pages of textured surfaces made of materials like fur, wood, burnt paper, and straw. Miranda Brandon’s playful, conscious-raising DIY Bird Populator offers visitors a set of prints to take home, which include photographic images of extinct and endangered birds like the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, the Huia, and the Kingfisher done in paper-doll fashion so you can cut one out, place it in a safe new environment, photograph it and add to their “population” on Facebook. Another project, 6 Words Minneapolis by librarian-poet-artist, Emily Lloyd, is a revival of a public art project she staged in 2011-2012 that asked Minneapolis residents to submit a six-word memoir. At the Nash, visitors can likewise write their own short quip onto a Post-It note and hang it on the wall, but it’s more impressive to see the whole archive here.

There is another cluster of work in thinking making living that functions like documentation of social practice projects that have taken place outside the gallery. Some compelling examples include Emily Johnson’s set installation of fish lanterns from her multidisciplinary dance and storytelling piece, Niicugni (a Yup’ik directive to pay attention, to listen); Christine Baeumler’s documentary Bogs, A Love Story and accompanying Table Top Bog that includes a unique range of bog plants displayed in 19th-century specimen jars. Rachel Breen’s mural of Common Milkweed is on view, from her series The Heirloom Project, which depicts paintings of heirloom seeds and plants made from stencils produced with a sewing machine that currently installed on a half dozen garages in the Kingfield neighborhood in Minneapolis. The collaborative aspects of these projects are not something Nash Gallery visitors are witnessing first-hand: we don’t share in the many fish lantern-making workshops led by Johnson, or directly follow the ways Baeumler’s research led her to co-produce a bog on the rooftop of the Minneapolis College of Art and Design with an ecologist and an engineer; we don’t participate in the coordinating Breen has done with the Kingfield Neighborhood Association and garage owners to produce her project. But all three artists, through their display decisions in the exhibition and by the very materiality of their projects (i.e. dried fish skins, luscious green plants, charcoal on wall), resist the remove you’d expect from accessing just the secondary experience of a project done elsewhere. Rather, they engage our senses with environments and ecosystems outside the gallery walls; Breen even invites visitors to take away milkweed seeds to help restore this plant, once common and widespread in the Midwest, now drastically reduced because so much of its habitat has been destroyed.

Finally, I’ll mention two works in thinking making living that don’t fit my definition of socially engaged art, in that they don’t require active participation (beyond looking) and weren’t made in collaboration with others (to my knowledge), but which nonetheless provide an important commentary on participation. John Kim’s sculpture, Uneasy Dreams of Civilization, is a reflection of pirate utopias, temporary autonomous zones and anarchist societies which arose in the 17th and 18th centuries amidst the burgeoning capitalist Euro-American society then riddled with warfare, slavery, and great division between rich and poor. Comprised of three white model ships named after island utopias—Libertatia, Utopia, and Mallard Island—each vessel is positioned atop a pedestal a few lengths from one another. The ships communicate with one another through an autonomous information network, as seen by a system of interconnected red lights. According to the label, the “ships are a romantic dream of freedom from repression and political control.” The networked ships represent the pirate utopias of the past and present, which today take the form of temporary virtual anarchist communities that are experimenting with ways to share information that aren’t in the hands of our government, like a regulation free marketplace or data encryption technology which keeps information private.

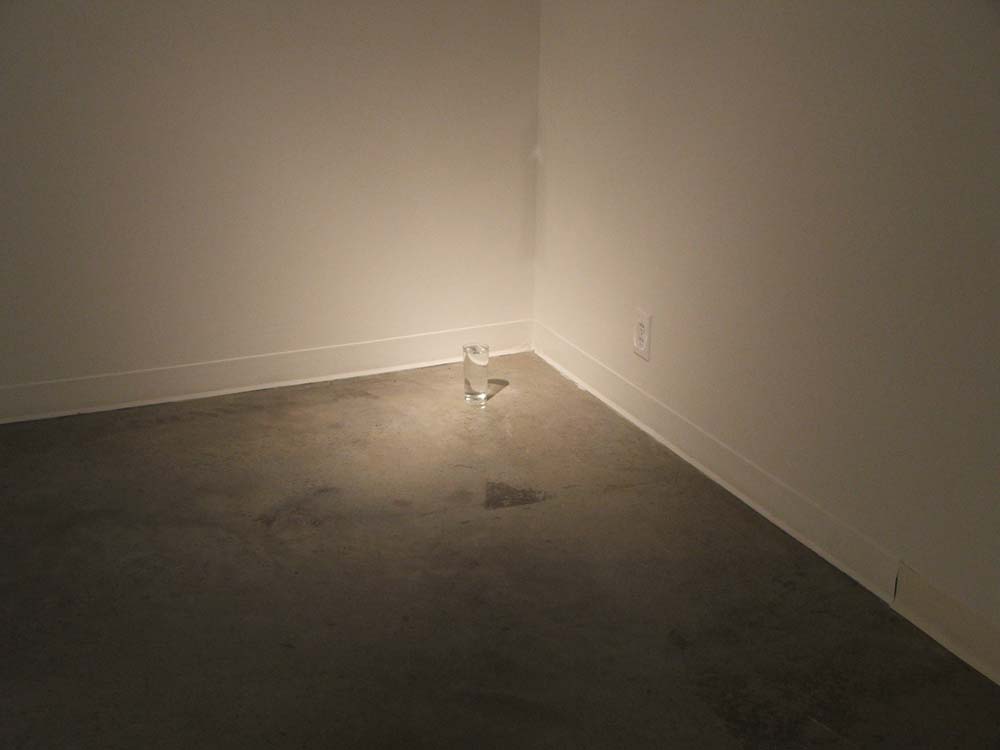

Equally clever is a work by Nate Young, called A Container for the Projection of a Political Assertion. Humbly resting on the floor in one corner of the gallery this seemingly simple piece is comprised of a tall drinking glass filled to the brim with water. I actually missed it on my first trip to the Nash Gallery — which seems precisely the point. A near invisible object put in a vulnerable, marginalized position where it could be spilled (or worse, broken) Young’s piece offers deft commentary on the failure of our participatory democracy. A society which ignores the voices and needs of the 99% is ripe for disaster. In both of these works, it’s the very absence of participatory tactics and the space they demand for contemplation, that give them agency.

Artist Allison Bolah said it best, in a recent panel lecture for thinking making living; she described “social practice [as] troubling the recipe of how art is made.” I would add that this work is also troubling the recipe of how art is experienced—whether it’s sharing a community meal on a half-mile stretch of tables set up on a city street, or confessing to a criminal offense you committed without getting caught—the lines between art and life are increasingly blurred. After several trips to thinking making living, I still have more questions than answers about what constitutes socially engaged art and why (and for whom) it needs to be categorized as such. But I suspect it’s that shared process of inquiry done through thinking, making, and living that keeps me coming back for more.

Related exhibition and event information: thinking making living is a group exhibition and series of related public programs investigating socially engaged artistic practices at the University of Minnesota’s Katherine E. Nash Gallery in Minneapolis from September 2 through December 13, 2014. On Wednesday, December 10 from 6 to 8 pm in the gallery, there is a related panel conversation, “Art Inside Out: Institutions and Engaged Creative Practices” moderated by Christina Schmid and featuring Roger Cummings of Juxtaposition Arts; artist and MCAD associate professor, Natasha Pestich; Sarah Schultz former Director of Education & Curator of Public Practice at the Walker Art Center; and Plains Art Museum Director and CEO, Colleen Sheehy.