Vasili Nechitailo – Russia’s Mid-Century Master Craftsman

Andy Sturdevant muses on the extensive retrospective of paintings by mid-20th century master Vasili Nechitailo, on view at the Museum of Russian Art, and on an alien art historical track running parallel to that with which we're familiar in the West.

THE STEPPES OF SOUTHERN RUSSIA ARE LOCATED on roughly the same latitude as our own country’s Great Plains, right around the 45th parallel, halfway between the equator and the North Pole. In Russia, this area consists, in part, of the land between the Black and Caspian Seas, and in the U.S., it spreads from the western part of Minnesota into the Dakotas. Besides being the breadbaskets for respective nations, these two regions share many of the same physical characteristics — both are semi-arid, flat, and treeless, with sweeping grass prairies and wide-open skies above.

This is the region where Vasili Nechitailo (1915-1980) grew up, and which is depicted in many of his paintings currently on exhibition at the Museum of Russian Art in south Minneapolis. The open, sunlit landscapes will look familiar to anyone who has spent time in America’s high plains. Walking through the galleries, one imagines the scenes before them could just as easily be North Dakota, or the wind-swept Pipestone region of Minnesota. The prairie is such a forceful, distinctive part of the geographic (and psychic) makeup of the scenes in Nechitailo’s paintings, that on some level the agricultural workers he depicts seem like they could be cousins to our own. Even the way the sunlight falls on and around them seems oddly familiar.

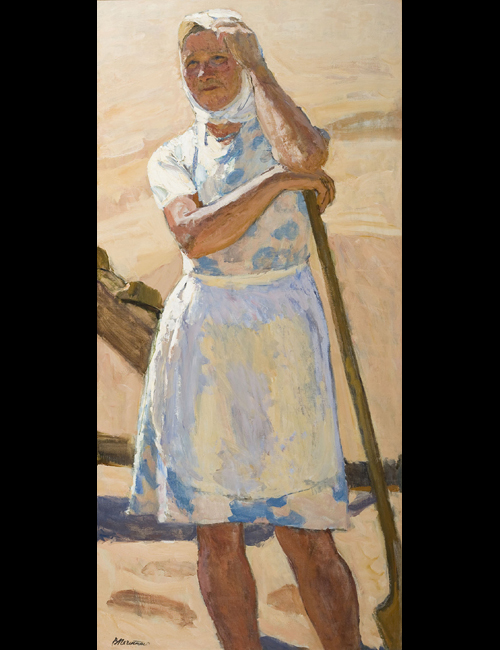

And with the almost vertigo-inducing absence of landscape markers in the prairies, light takes on an almost physical presence. It’s this feature which, more than anything, is the subject of much of Nechitailo’s work — the way light hits his subjects, whether agricultural workers in the field, or enormous piles of grain. Nechitailo’s style of painting is fast and loose, executed with knives and stiff brushes, the paint piled on the canvas. Typically, the lighter the color of the paint, the heavier it is applied. Nechitailo applies the white paint in such a thick impasto to the side of a figure facing the sun, for example, that the effect is almost three-dimensional. One senses a physical weight to the light.

Nechitailo was one of the most celebrated artists in the Soviet Union during his lifetime. His father, a farmer, fought in the Russian Revolution on the side of the Bolsheviks. Nechitailo, too, was a true believer. “At home the revolutionary conflict was stark and irreconcilable,” he wrote of his father’s experiences. “[with] the rich counter-revolutionary White Cossacks against the destitute peasants who joined the Red guerilla forces and fought to the last drop of blood.” In the post-Stalinist era, during the relative prosperity of the 1950s and ’60s, Nechitailo’s paintings enthusiastically celebrated abundance, collectivism, and hard work. As an artist, he reaped the rewards of the Soviet system. In addition to receiving extensive training and education, he was able to paint prolifically with generous state support throughout his career. It’s remarkable that the Museum of Russian Art has the space and resources to present a full retrospective of his work — almost sixty paintings are included in the exhibition.

Though he settled in Moscow early on, Nechitailo often returned to the region of his birth, and he continued to paint the landscape and the people he knew there throughout his life. The paintings in this show are uniformly marked by careful attention to detail, powerful evocation of place, and the sort of masterful handling of color one doesn’t often see in paintings of any era.

It’s worth noting here, while looking at the full sweep of the artist’s work, that regardless of the agricultural and collectivist themes evident in his paintings, Nechitailo never seemed to subordinate his aesthetics to ideology. The paintings hold up first and foremost as paintings — not as ideological documents or political statements. Looking at Soviet art from a Western perspective, it’s tempting to nit-pick the subject matter, looking for evidence of nationalistic posturing or blatant propagandizing. Much of Nechitailo’s work does undoubtedly paint a sunny, optimistic vision of Soviet life; however, despite the state’s seal of approval, his work never feels like out-and-out propaganda. Rather, Nechitailo comes across primarily as a craftsman, whose interest in the people and places of his home country were informed by his experiences, but whose most pressing interest had less to do with politics than with getting the color and light and form correct — something he does consistently.

________________________________________________________

Despite the similarities of light and landscape, much about Nechitailo’s paintings remains deeply alien to Western eyes — his work steps into a completely different narrative than the one we’re used to assigning Soviet artists of his time.

________________________________________________________

Beyond the familiarity of the light and expansiveness of Nechitailo’s beloved steppes, upon viewing piece after piece, you can’t help but notice that much about his paintings remains deeply alien to Western eyes. And this is exactly why seeing all of his work in one place makes for such a unique experience. It’s unlikely that seeing one or two of these pieces in a group show setting would make much of an impact, but seeing an entire retrospective of a whole life’s worth of work assembled together, one notes the nuances. One also notices, at first gradually and then with more insistence, that in terms of art history, Nechitailo’s work steps into a completely different narrative than the one we’re used to assigning Soviet artists of his time. This is not Cold War work that acts in tandem with or as a reaction against the decadence of the West. In fact, the work really has no relation to the West at all. It exists wholly on its own terms, in its own time and space.

Another august cultural publication in the metro area recently covered this show, and somewhat confusedly referred to the work as “impressionist.” On first blush, the paintings do bear certain superficial similarities to impressionism, perhaps in the way the paint is handled. Using a term like “impressionism” is an easily understood shorthand way of putting certain types of painting into a context — loose brushwork, with emphasis on light and landscape. However, looking closer at these paintings and thinking about how, why, and when they were made, one realizes how superficial the similarity to that late 19th-century genre really is. This is something one becomes keenly aware of when reading the dates on the title cards: most of these paintings were done in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. With that in mind, it’s impossible to see these pieces without thinking of the art being made at the same time in the U.S. — Nechitailo’s paintings bear no resemblance to the type of work that was created by his American counterparts in the post-World War II period. In fact, apart from the more universal languages of color, form and technique, his pieces simply don’t exist in the continuum of 20th century painting at all as we in the West have learned to understand it. For example, the pop art or abstract expressionist painting from one of Nechitailo’s U.S. contemporaries can’t be separated from the idea of “the market,” or from names like Leo Castelli and Peggy Guggenheim. It’s a little disorienting to see Nechitailo’s paintings, created at the same point in history, and realize how different the circumstances of their creation truly were.

While looking at Nechitailo’s late work from the 1970s, I thought amusedly about a passage I’d read recently in Bay Area conceptual artist Tom Marioni‘s memoirs of working in that same decade: “No painters emerged in the ’70s,” he posits. “Name one.” Marioni further contends that during that period, “painting was essentially dead, just like jazz.” Knowing what we do about American art of that time, this is a hard statement to argue with. There was no painting in the 1970s art mainstream — the work of that period was conceptually driven, or site-specific, and painting only came back into vogue in the 1980s when market forces began pushing the work back in that direction. But these handy temporal signposts we carry around with us are utterly and completely irrelevant when faced with Nechitailo’s paintings of mountain villages and collective farms.

There is something inherently resonant about the prairie setting of Nechitailo’s paintings, and something very pleasing in their deft execution. But a large part of the pleasure of this exhibition lies in the scale of the show, and its ability to immerse the viewer in an art history that runs perfectly parallel to the one more familiar to us in the West.

________________________________________________________

Related exhibition details:

The Art of Vasili Nechitailo (the second installment in a “Discovering 20th Century Russian Masters” series of exhibitions) will be on view at the Museum of Russian Art in Minneapolis through February 27, 2011.

________________________________________________________

About the author: Andy Sturdevant is a writer, artist, arts administrator and layabout based in South Minneapolis. He is the host of Salon Saloon, a monthly live-action arts magazine held every fourth Tuesday at the Bryant-Lake Bowl. He recently wrote an essay on the visual culture of the Midwest that will appear in the catalog for The Spectacular of Vernacular exhibition, opening at the Walker Art Center in January 2011.