Two Novelists, Six Books, and the Conundrum of Chick Lit

Heather McElhatton and Norah Labiner write novels that land in opposite ends of the fiction marketplace, thanks more to marketing decisions than substantive differences. Stephanie Wilbur Ash chats with both of them to dissect the "chick lit" conundrum.

WRITING FICTION TODAY IS TOO OFTEN A SUCKER’S GAME. In the novel-writing business, the publishers cutting the checks have become adept at hedging bets. Forget big advances, here’s how a typical book deal works: Write your novel on your own (it may well take you years). A publisher might pay you for this work, but probably not. If so, that publisher will decide how much, and the amount you receive will have less to do with your talent or hard work than with how much the publisher thinks the work can garner in sales (with as little marketing and publicity effort as possible). For the vast majority of writers, the payout is hardly extravagant–usually it’s not enough money to live on, even for one year.

Of course, what I’ve described doesn’t reflect every novelist’s experience, but it is what most beginning and mid-list novelists have come to expect. Take the recent New York Times essay “About That Book Advance” by (former Minnesotan) Michael Meyer, for example: his account of business-as-usual in publishing these days cites novelist (and yet another former Minnesotan) Walter Kirn and Authors Guild president Roy Blount Jr., each of whom make similar points about the harsh business realities of publishing these days.

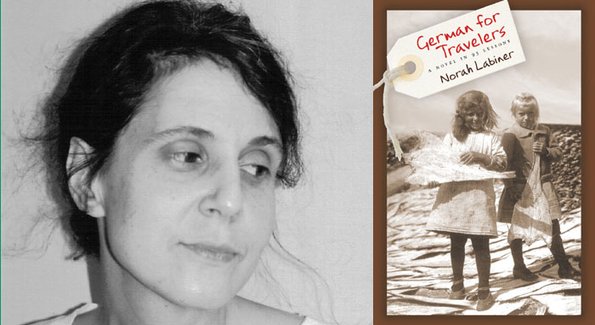

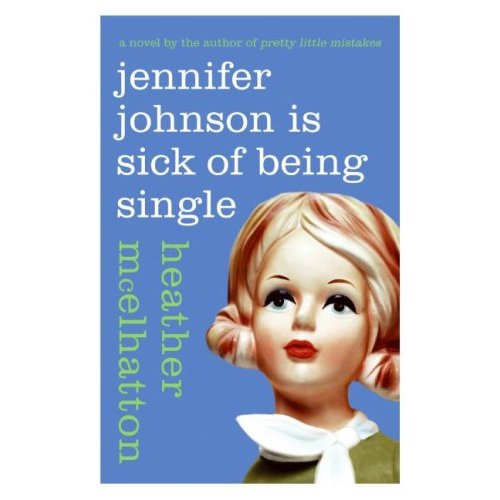

I was reminded of these industry indignities when I interviewed Minneapolis novelists Heather McElhatton and Norah Labiner within days of each other, just before their new books were due out. HarperCollins released McElhatton’s second novel, Jennifer Johnson is Sick of Being Single, in early May. Local publisher Coffee House Press released Labiner’s third novel, German for Travelers, at right around the same time.

Demographically speaking, these women are eerily similar — both are somewhere deep in their thirties (or a little more, in Norah’s case), partnered, with no children. Both are long-time South Minneapolitans — McElhatton is a Twin Cities native, and Labiner came here from Michigan more than ten years ago for the MFA program at the University of Minnesota. And each can comfortably use “novelist” as her job title; both women have published or contracted three books thus far (McElhatton’s third is due out next year). Even weirder, they both have puppies with retro man-names: Labiner has Roy, McElhatton has Walter.

And both writers are amazing at what they do. Buy their books.

________________________________________________________

If the main character is single, under 40, having sex, living in contemporary society, not interacting with ghosts and/or vampires and/or aliens, not a victim of a crime, not too smart or too weird, and if she is bound by the constraints of space and time, the book will probably be marketed and sold as “chick lit.”

________________________________________________________

As demographically close as they may be, the kinds of novels Labiner and McElhatton write are not, really. And how those differences play out in bookstores says something about what novelists, in general, can expect from the business — and, in particular, what women novelists can anticipate about the way their books will be sold. Writers grapple not only with the above-mentioned hurdles typical of the literary marketplace, but also with the fact that novels featuring young women as protagonists are almost completely dominated by the ever popular, sales-driven “chick lit” genre. That is, if the main character is single, under 40, having sex, living in contemporary society, not interacting with ghosts and/or vampires and/or aliens, not a victim of a crime, not too smart or too weird, and if she is bound by the constraints of space and time, the book will probably be found on those long lengths of chick lit tables, front and center at your local big box bookstore or filed under “chick lit” on Amazon. It’s not just the retailers making those placement choices. Often agents, editors, and publishers will push a writer’s manuscript in that direction.

And for good reason: these marketing decisions, whether to designate and publicize a book as “literary fiction” or “chick lit,” make crucial differences in the book marketplace — such choices, rather than judgments of quality or critical success, largely determine the scale of readership and sales for any given book. While the market for literary fiction is somewhat limited, chick lit sells very well.

McElhatton, whom I interviewed one late April afternoon at her Kenwood apartment, has taken her sharp wit, dark humor, and sexually active protagonists and used it all to dance on that chick lit table. It’s an act of celebration and defiance. When I interviewed her she was casual, funny, animated, and open about the practical benefits of such a classification — even though her books don’t exactly follow the easy chick lit formula. Instead, both of McElhatton’s books, when read on their own terms, feel more like a subversion of it. Pretty Little Mistakes is a play on form: it’s a “Choose-Your-Own-Adventure” book for grownups, albeit with a racy female protagonist. McElhatton’s second novel, Jennifer Johnson is Sick of Being Single, was actually tailor-made for the chick lit genre — complete with a gay best friend, a younger sister’s impending wedding, and weight anxiety. But the novel’s dark outcome totally betrays the usual formula in another hugely brilliant play on established forms.

McElhatton, herself, wasn’t a reader of chick lit going into Jennifer Johnson (although she did browse the Shopoholic series, she says); but it’s clear she knows where her novels will do best in the marketplace. “This is just my world. My world is a dark comedy, apparently,” she says. And, “If there is something called chick lit, then there’s no reason [the genre] can’t evolve.” In fact, she is mostly grateful that her book has landed in that marketing niche, simply because it means more people will likely read it: “In this market, you’re lucky to be in a group.” Indeed, the first printing for Jennifer Johnson was a whopping 50,000 copies. (The typical run for an author not already on Oprah or a bestseller list is less than half that.) McElhatton is also the featured author for the month of June at Target, which means her new novel has its own end cap in Target’s book sections nationwide. There’s a television series in the works for Pretty Little Mistakes; and the sequel to her popular debut novel is due out this time next year. These aren’t just lucky breaks, or solely a result of her talent. McElhatton, who worked in media before becoming a novelist, is a well-connected, hard-working self-promoter, updating her clever website and blog with her books’ media accolades regularly.

THAT’S ONE WAY TO DO IT. Norah Labiner represents another. A noted recluse, there is no trace of Labiner on the internet that wasn’t put there by her publisher, reviewers, or the National Endowment for the Arts. You can’t read an AP story about her in newspapers all over the country the way you can about McElhatton. Labiner does not blog. And though her three novels all have female protagonists, you would never call them chick lit.

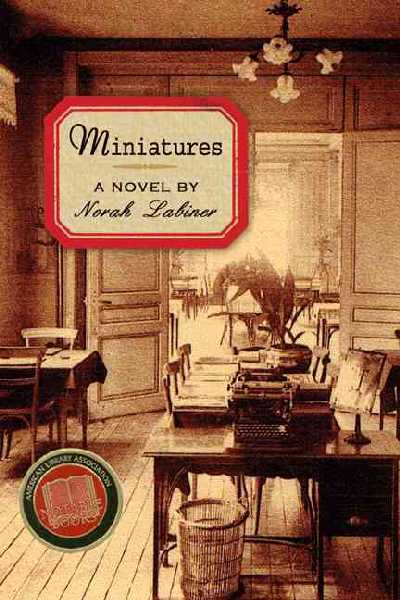

I met Labiner at Bryant Lake Bowl, within walking distance of her neighborhood. I found her to be charming, thoughtful and, like McElhatton, very funny. We talked about her latest novel’s complicated structure; it’s written in a nonlinear narrative style, as were her earlier books. We chatted about her liberal use of literary allusions — Freud, in the case of German for Travelers; Proust and poet Ted Hughes in Miniatures; and Hamlet in Our Sometime Sister — and about the way she likes to directly address the reader on the page, employing the second person, “you,” in her novels.

________________________________________________________

The young woman who might have been Labiner’s reader won’t likely run across her book front and center on the chick lit table at the big box bookstore. It’s equally unlikely that she’ll stumble on a review in the latest issue of Cosmo or People Magazine or Vanity Fair. She won’t hear about the book when it is made into a movie or TV series, because it won’t be. So how is this might-have-been young reader supposed to know about Labiner’s new book, let alone read it?

________________________________________________________

And then we talked about chick lit. Labiner knows it would be easier to publish books, and more copies of them, if she could write in a way that even sort-of resembled the genre. But she can’t. She cannot write a “conventional” novel, even though she cringes at that label, saying, “I hate when people talk about the ‘conventional’ novel. I don’t think any novel should be conventional.” And chick lit is a conventional form, of course. (Though, this is weird: Labiner’s two main protagonists in German for Travelers are a Hollywood starlet and a romance writer. If you never got beyond a plot blurb, you might mistake the book for chick lit.)

It has taken Labiner at least five years to write each of her books. Her modus operandi is to extend the lives of other pieces of literature by writing her own works of fiction around them. Words like “classical style” and “experimental” and “prose that summons Marcel Proust and the Bronte Sisters” (arguably the original ladies of chick lit) are peppered throughout reviews of her novels. While she’s writing, Labiner says she never considers a story’s possible adaptation in other media, like movies or Broadway shows or even public readings. “I’m a specialized novelist,” she says. “I am specialized to the page.”

The financial realities of publishing are stark: as fewer people read books, this “specialization to the page” becomes less and less tenable. Despite her literary accolades — she’s a winner of an American Library Association “Notable Books” Award, a Minnesota Book Award, and a finalist for the Barnes & Noble “Discover Great New Writers” Award — her books haven’t earned her a place on the national cultural scene, and barely a whisper even in local popular culture. In fact, in spite of Coffee House publisher Allan Kornblum’s incendiary 2002 quote in Publisher’s Weekly —“If we publish Norah’s third book, it will be an indictment of New York publishing”— no big New York publishing house picked up German for Travelers. Instead Coffee House did, printing 5,000 copies of the book- one-tenth the initial print run for Jennifer Johnson is Sick of Being Single. You won’t see Labiner’s book on the big chick lit table at a Barnes & Noble in Flagstaff or Fort Worth. You’ll have to dig for a copy at a Minneapolis Barnes & Noble. It certainly won’t be on any Target end caps. German for Travelers will not sell 50,000 copies. It will probably not sell through all 5,000 copies.

Now, it is important to note that Labiner has gotten support outside the marketplace, notably a $20,000 fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 2002. (Novelists do still occasionally have such routes to income.) And it’s important to note that not everyone likes to read literary fiction — and the marketplace is ever tipped in favor of more entertaining reads. As acclaimed novelist T.C. Boyle observed to the New York Times, “As much as we intellectualize our literature, really, it is an entertainment. All art is entertainment at root.”

But it’s also important to note that the primary demographic group for chick lit is comprised of young women, ages 15 to 30 — women who often don’t yet know quite what they like, who might be surprised to find they are, in fact, entertained and moved by the meatier prose, more complex literary devices, and more sophisticated themes found in literary fiction.

Oh, if only these young women readers could get to such novels! But where is a young Minnesota woman supposed to learn of the new book by her hometown literary novelist? She doesn’t read the local newspaper, much less the New York Times Book Review — such media isn’t even trying to get her attention, really — so she won’t read about it there. As mentioned above, she won’t run across such books front and center on the chick lit table at the big box bookstore; she won’t see a literary novelist like Labiner interviewed on network television news; and it’s unlikely that she’ll stumble on a review in her new issue of Cosmopolitan or People Magazine or Vanity Fair. This might-be young literary fiction reader isn’t going to hear about it when it is made into a movie or TV series, because it won’t be.

This young woman’s best bet for finding Norah Labiner’s new book is probably in her contemporary literature class, taught by a culturally plugged-in high school or college instructor who happens to have a commitment to keeping track of work by local authors. Or, if this young reader is an arty hipster, she might find out about German for Travelers in the Minnesota free press focused on the arts, a handful of independent bookstores, or on a book-sharing website like Good Reads.

YOU KNOW WHAT THE GREAT IRONY OF ALL THIS IS? Despite their differing market appeal or publicity classifications, it is fascinating to note just how similar the literary works of McElhatton and Labiner are. It’s not just their personal lives that are strangely parallel. Both have written novels distinguished by the second-person direct address of the reader (“you”), and that’s not an everyday device. Both have written novels that successfully pull off unreliable, first-person narration by their respective protagonists (both female), with narrators who manage to at once irritate and evoke sympathy from the reader. Both authors have written novels that play with nonlinear narrative, and both writers’ books experiment freely with established prose forms.

And both Labiner and McElhatton share a confident awareness of who they are as artists; each author, in her chosen genre, is hitting her stride right now.

Though I don’t think these writers know each other, I like to imagine them waving colorful scarves in enthusiastic greeting as they pass each other while walking their dogs on Lyndale, or maybe even grabbing some breakfast together to commiserate about the greatest novel-writing hazard of all — actually writing the damn things.

With so much in common, I find it deeply ironic that the books written by Labiner and McElhatton are about as far apart in the marketplace of books as they can get. And that’s sad, too, because those artificial distinctions — where they’re shelved and who their books are marketed to — mean that these authors’ novels will probably end up equally far apart in audience size and book sales. The fact is, the same marketplace that directs the real (and potential) audience of reading chicks to prominently located tables laden with hot pink book covers — in bookstores, airports, and even in Target stores — inadvertently serves to keep other kinds of literature, novels written by and about women, hidden away in obscurity. Today’s novelist will have to do more than just write books if she also wants them to sell.

About the author: Stephanie Wilbur Ash is the only woman writer/performer in the Electric Arc Radio Show, and a freelance feature writer and book reviewer. She originally interviewed Norah Labiner and Heather McElhatton for the Decider. (Read the Labiner interview here, and the McElhatton here.) She also reviewed both their books for the Star Tribune. (A review of McElhatton’s book is here, and you can read the German for Travelers review here.) Wilbur Ash is currently is at work on her own novel about a married woman C.P.A. who falls for a vocational agriculture teacher in a small Iowa town. She’s not sure if it is or is not chick lit, but it does have some pretty good sex in it.