Toward a Greater Communion: Jérôme Bel and Pichet Klunchun, “Pichet Klunchun and myself”

Dance critic Lightsey Darst reflects on the collaborative dance-cum-cultural exchange by avant gardist Jérôme Bel and Thai dance virtuoso Pichet Klunchun, and on the challenges and rewards of trying to get inside arts emerging from unfamiliar traditions.

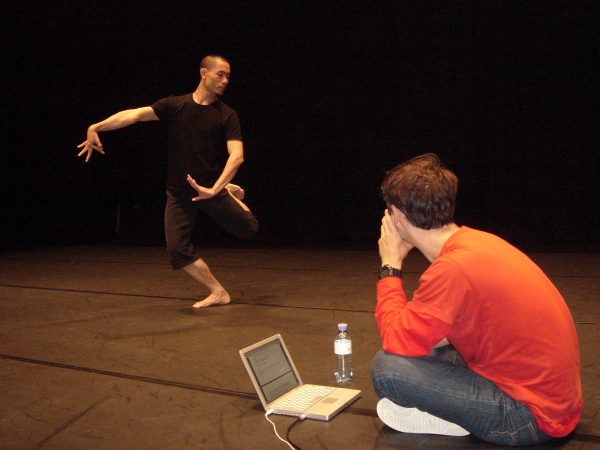

The idea behind Jérôme Bel and Pichet Klunchun’s Pichet Klunchun and myself is simple: two dancer-choreographers of very different backgrounds—one a French avant-gardist, one from the classical Thai tradition—talk to each other about the dance they make. What do we learn from their conversation?

First, as Bel interviews Klunchun, we learn a few tidbits about Thai classical dance. The style is called Khon; traditional performance is masked and recounts the stories of the Ramakien (Thailand’s version of the Indian classic tale, Ramayana); a speaker orates for characters as they move; female characters stand with their feet parallel, while male characters turn their feet out; etc. But these bits of knowledge only prove the irreducible strangeness of Thai classical dance to Westerners. Klunchun explains that there are four basic characters in Khon—man, woman, demon, monkey. This in itself makes Bel stare and the audience titter. When Klunchun demonstrates the differences between the characters, Bel calls the differences “tiny,” ostentatiously refusing to understand. Even without Bel’s underlined inflexibility, though, we’d be at sea enough. For Westerners, Khon is an exotic delicacy, apt to recall nothing so much as The King and I.

Apparently, then, we can’t choose to take on a new form of dance the way we would pick up pad thai in a buffet line. Watching Klunchun’s stylized, stately movements, even with information enough to decode his gestures, we’re seeing a flat surface of Thai culture, lacking the background to appreciate Khon as it was meant to be appreciated, from the inside. So the choice left to us is between the classical forms of our own culture—for Westerners, this generally means ballet—and contemporary dance.

When the tables turn and Klunchun begins to question Bel (with as little cultural sensitivity as Bel showed him), though, we begin to see that contemporary forms are themselves culturally conditioned. Klunchun follows Bel a certain distance, even appreciating the room Bel offers to the audience for their own thoughts, but there are places he’s not willing to go. When Bel begins to strip down in order to demonstrate the bodily manipulations of an earlier piece of his, Klunchun stops him. “No,” he says. Attending a season of performance at the Walker, you’re sure to see a few naked people (or, last year, lots). Westerners think of this as rebellious behavior, but we forget how long centuries of fascination with the nude and a tradition of artistic nudity have laid the groundwork for acceptably showing plenty of skin in avant-garde dance.

So an appreciation of classical dance (of any tradition) and the ability to fully join in the contemporary dance scene both require that you share (or at least have some context for) the underlying cultural assumptions of each form. As Klunchun explains, Khon now belongs to the tourists, because they are the only ones who see Khon, which has lost its place in Thai culture. Most Thai people, Klunchun asserts, don’t know what’s going on in Khon; they don’t get the gestures or the history, and don’t appreciate Khon’s view of the cosmos. Only if you are raised with the classical can you understand and have an intelligent taste for it. While our Western classical forms haven’t yet been relegated to the tourists, only a certain portion of the audience for art likes the classical forms, and perhaps a smaller portion actually understands them. We have undoubtedly moved some distance from the late eighteenth century ideas of life and the world order those forms enshrine, and it’s hard for non-initiates to get into the stately perfection of classical ballet or classical music.

This is all true, to some extent, but I find it rather gloomy—anti-universalist thinking at its most stringent. What are we to do if we can’t choose to go beyond our own tradition’s borders, but can only appreciate the art forms we’re raised in? Klunchun says he’s begun to create contemporary works rooted in Khon—Khon minus its tourist flare. He says his small audiences are steadily increasing, but also that mostly they don’t understand what they’re seeing. Bel creates work within a long Western tradition of troubling the theatrical space, and he seems almost defiantly happy within that realm. But I want to be able to see forms I wasn’t raised in. I want to learn. I want (and perhaps this is simply my overconfident Western critical sense speaking) to apply my eye to everything.

Luckily Pichet Klunchun and myself offers wiggle room. Intentionally or not, the existence of the performance itself goes some way to contradicting its ideas: here are a Western avant-gardist and a Thai classical performer creating work together. What exactly the wiggle room is, I can’t quite say. We’re approaching the old conundrum of the theoretic impossibility of communication versus the seeming reality of communion. All I know is that I wanted to be left alone with the two dances, Klunchun’s Khon and Bel’s creations, without any more talking.

Maybe we each can understand only a few things from the inside. Should that stop us from trying to reach beyond? After all, if we’re all in our own bubbles, that means that even among Khon performers there are a thousand different versions of Khon. The Western viewer’s would certainly be less nuanced than theirs, but so long as we understand that, why not stretch our experience?

About the writer: Lightsey Darst writes on dance for Mpls/St Paul magazine and is also a poet and editor of mnartists.org’s What Light: This Week’s Poem publication project.

What: Jérôme Bel and Pichet Klunchun: Pichet Klunchun and myself

Where: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

When: November 14-15