THEATER: This is the Way the World Ends

Performance critic Lightsey Darst reflects on a new show, "Socktesting," which explores the uneasy terrain between day-to-day reality and the ever-present specter of death.

REALITY IS A PUZZLE. Certain things in life are indisputably real: the need to breathe, for example, birth, or death. Certain things are patently not real: movies, video games, acting. Certain things must be regarded or there will be consequencestaxes, laws, local mannersbut their reality is tenuous, since they arise from a human system, a created system. In fact, when you begin to examine this question more closelywhat is real and what have we made up?even previously sure lines begin to blur. Its not clear, for example, that stage acting is significantly less real than our own learned behavior; its all imitation of imitation. And hard facts lose their edges in our ignorance of their workings: we dont know much about birth; we know less about death.

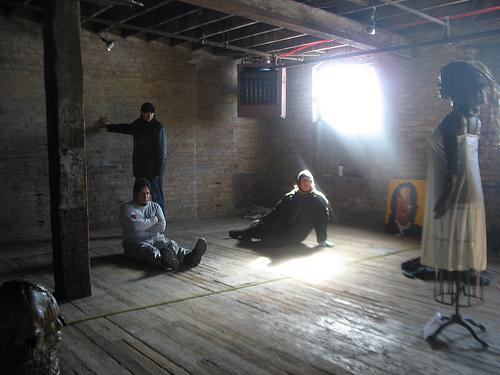

Stare at the puzzle too long and you begin to feel yourself falling through layers of real and false, meaning and meaninglessness. What is, after all, clear about this life and what we should do in it? Its a vertiginous feeling, and its provided by Mark Abel Garcia and Megan Mayers new play Socktesting (this month at the Soap Factory). Socktesting is based on a simple premise: if you cram six people into a small space and slowly suffocate them over a period of a few days, what happens? Leaning too heavily on such an idea would lead us into a voyeuristic poor them mode, but Garcia and Mayer skirt this danger by never explicitly alluding to the premise during the show (or even in the accompanying programits only stated on the shows website). Instead, the audience is left to struggle to understand whats real in the dystopian scene enacted before them.

A couple confer with a doctor about their baby; the baby is simultaneously born and unborn, capable of cooing but still under medical review lest the quality of its coo indicate some fatal defect. When we finally get a look at the baby, it turns out to be a paper clip that the doting mother holds in the palm of her hand. Meanwhile, the mothers friend Darnelle is convinced that her husband Bill is still alive, so much so that when the mother mildly says, Bill was your husband, Darnelle shouts Is is is! and insists on the mothers repeating it with heris is is! Going to work involves everyone shuffling around in a corner, grunting and pushing, and occasionally stopping to yell at each othera pretty fair approximation of the usual morning traffic jam. Working means typing mechanically. Again, this will be familiar to many of us. But when one man points out to his friend, whos sitting on the floor typing on his thighs, that Youre not doing anything, theres a tumble and slide of our usual interlocked realities and unrealities.

This vertigo is aided by the shows design. Socktesting takes place in a corner of the Soap Factory, hemmed in on the two open sides by audience chairs. Obvious as this arrangement seems (particularly in the world of low-budget alternative theater), I cant recall ever having seen it before. Claustrophobia is the effectnot for the audience, but for the characters/performers. I couldnt help feeling that we, the audience, were doing something to the characters/performersconstraining them, forcing themwhich, in some sense, we were. Louise Delfss costumes of blank white, frayed at the edges and only made into a semblance of ordinary clothes (unfinished pants, slapdash shifts), add to the feeling of contrived, false reality. One character seems more part of the design than the play: Shadow simply follows other characters around, mimicking their actions, as if shes not human herself.

Watching the closed universe of Socktesting, youre apt to forget the basic idea: that all the stage action is simply the characters defense mechanism against their central dilemma, suffocation; it’s a reflexive pretense of somewhat normal reality. But remembering the setting doesnt result in a oh, it was all a dream! settling for the audience; instead, it points up the fact that our own situations are similar. We, too, are dying; we cope with that overwhelming truth, in the meantime, by staying busy with emotional quandaries that arise from the human systems of habit and culture weve created. We dont live in unmediated reality. And Garcia and Mayer suggest we cant: were social animals, bound to invent systems of relation, laws, and rules. Rules are, one character exclaims as hes enjoying (mimed) fellatio, our highest desire.

I wouldnt call Socktesting entertaining. Its sometimes funny, and its certainly well-acted by the cast of Mimi Holland, Mats Sexton, Arnie Roos, Jody Bee, Samuel Van Wyk, and Heather Stone. But being in a state of perpetual instability is no ones cup of tea (and perhaps the destabilization does last a bit longer than necessary). Still, its good for us on occasion. I recognize seeing Socktesting as one of those experiences I dont particularly enjoy at the time but remember and think about later. And, however disorienting Socktesting is, its not truly a downer. In recognizing our dependence on social systems, Garcia and Mayer also look for what we get from those systems, what we needand they come up with love. In this way, Socktesting reminds me of Matthew Arnolds “Dover Beach” (1867), with its bitter, yet still faintly hopeful conclusion:

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

What: Socktesting created and directed by Megan Mayer and Mark Abel Garcia

Where: The Soap Factory, Minneapolis, MN

When: June 12, 13, and 15 at 8 pm

Tickets: $15 ($10 with student ID)

About the writer: Lightsey Darst writes on dance for Mpls/St Paul magazine and is also a poet and editor of mnartists.orgs What Light: This Weeks Poem publication project.