between friends: On Mourning, Mirrors, and Togetherness in Extraordinary Times

A dialogue on love and loss in a two-person exhibition by Nyeema Morgan and Mary Simpson at David Petersen Gallery considers the nature of friendship and the slow transformation of ordinary togetherness

“It is more worthwhile to love than to be loved,” wrote Aristotle, the philosopher—literally, a lover of knowledge—over 2000 years ago. Promptly, I run the idea past a friend of mine who recently married: “I’m not sure about that,” she replies and looks around as if to inventory the enormous new old house her husband bought to start off their wedlocked life. “It feels pretty good to be loved.”

Aristotle, far from dissing the occasional usefulness of our emotional bonds, was not writing about romantic love, though, which is a fairly recent invention in the history of humans, with intimate (if discomfiting) ties to the Enlightenment and the colonial project.1 Instead, his discussion is centered on philia, the affection involved in friendship: use, virtue, and pleasure serve as the three roots and reasons to enter into such attachments in the first place. To be-friend is to set an intention; to fall in love—happens to us. Or so popular romantic myths would have us believe.

In contrast, philia leaves our agency intact and grants us access to knowledge: “life, breath, the soul, are always and necessarily found on the side of the lover or of loving, while the being-loved of the lovable can be lifeless,” proposes Aristotle. “One cannot love without living and without knowing that one loves, but one can still love the deceased or the inanimate who then know nothing of it.” In more contemporary parlance, “it is possible to be loved (passive voice) without knowing it, but it is impossible to love (active voice) without knowing it.”2 Unsurprisingly, the philosophical lovers of knowledge through the centuries agree: to love is more worthwhile than to be loved. Knowledge beats ignorance.

Today, still, thinkers and theorists turn to Aristotle when mining philia. Post-pandemic, the sentiment’s cultural currency seems on the rise. Humbled by an epidemic of loss, we ask with new urgency, who do we want to show up for? How do we want to share a life, what does that look like, and with whom? between friends, a two-person show at David Petersen Gallery in South Minneapolis, taps into these questions and brings together works by Nyeema Morgan and Mary Simpson.

Works on paper cluster in small constellations and pairs, as if the artworks, too, were befriending each other. One sculpture stands by itself, off-center, a black side table with delicate, curved cabriole-style legs. Simpson blackened the table with an 1800-degree torch. Transformed not destroyed, its smooth surface holds carved, bas-relief patterns that recur in her two-dimensional pieces. When I visit, David Petersen encourages me to touch the table: the artist wants others to leave a trace on the work, not by one decisive gesture but through the gradual accumulation of one touch after another. A slow transformation, perhaps a metaphor, for what friendship is and does.

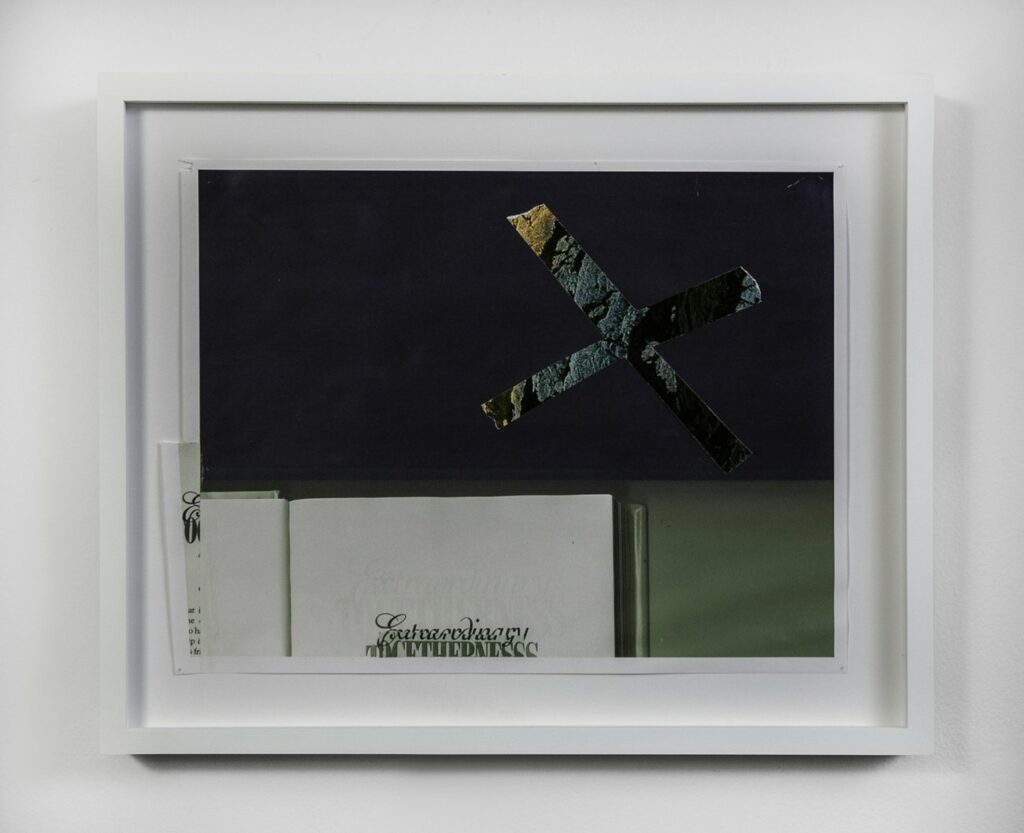

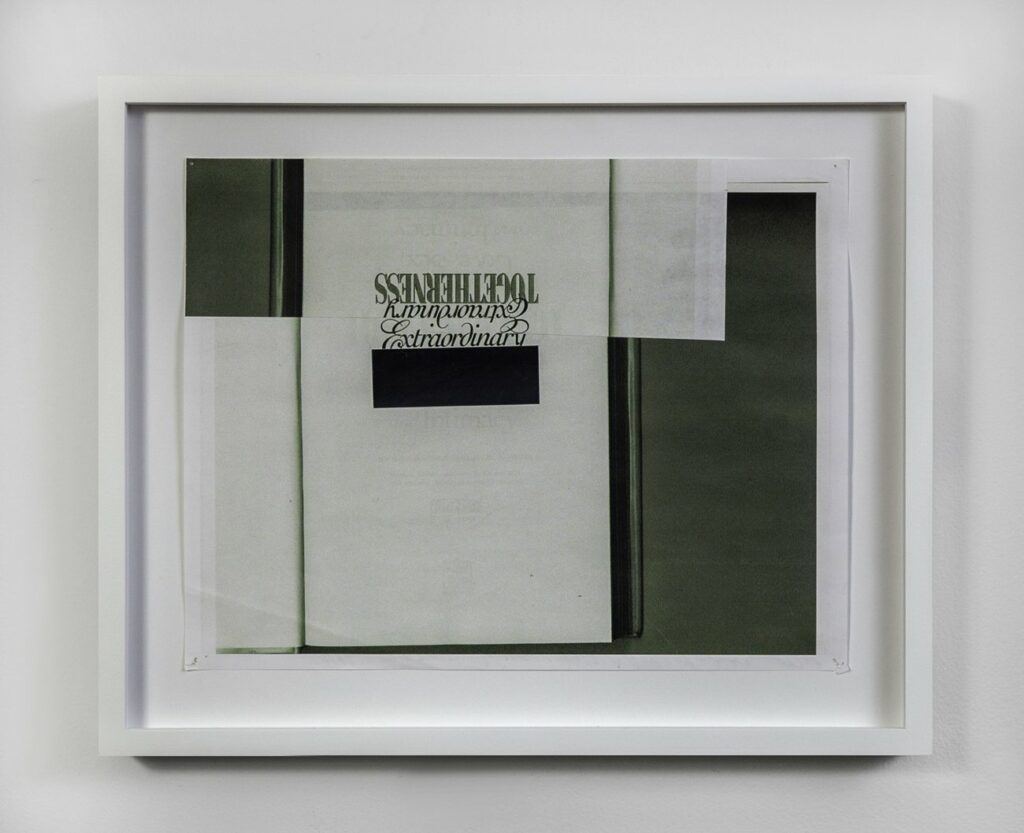

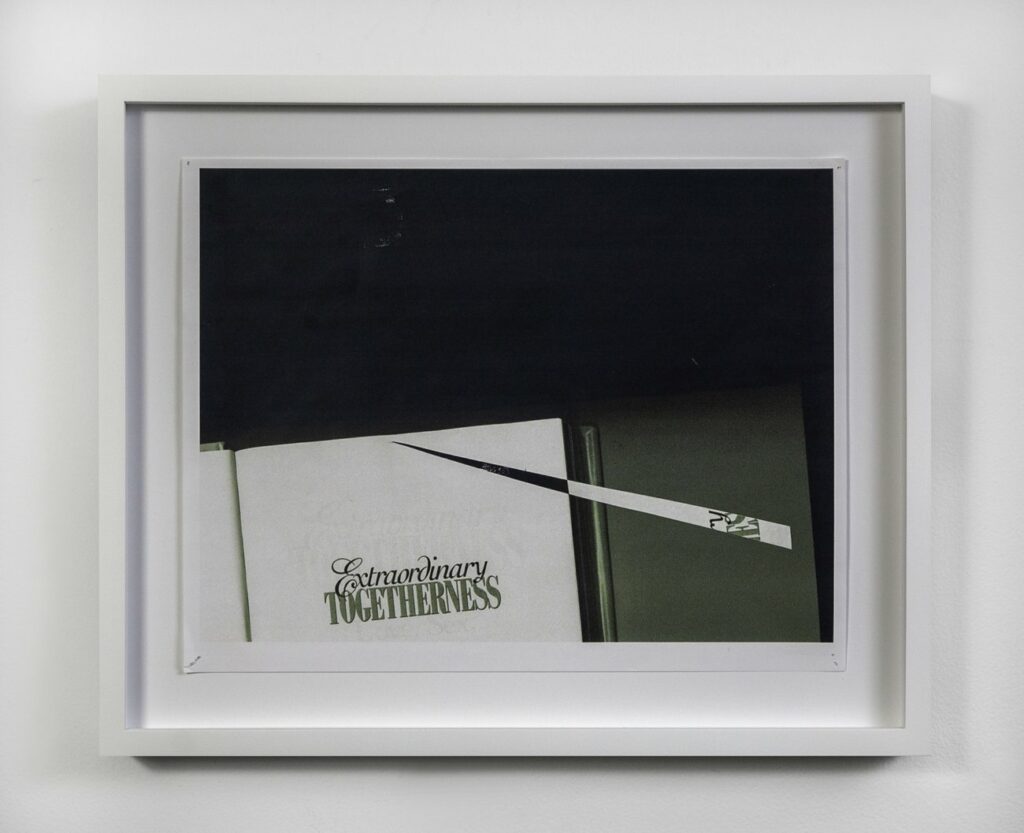

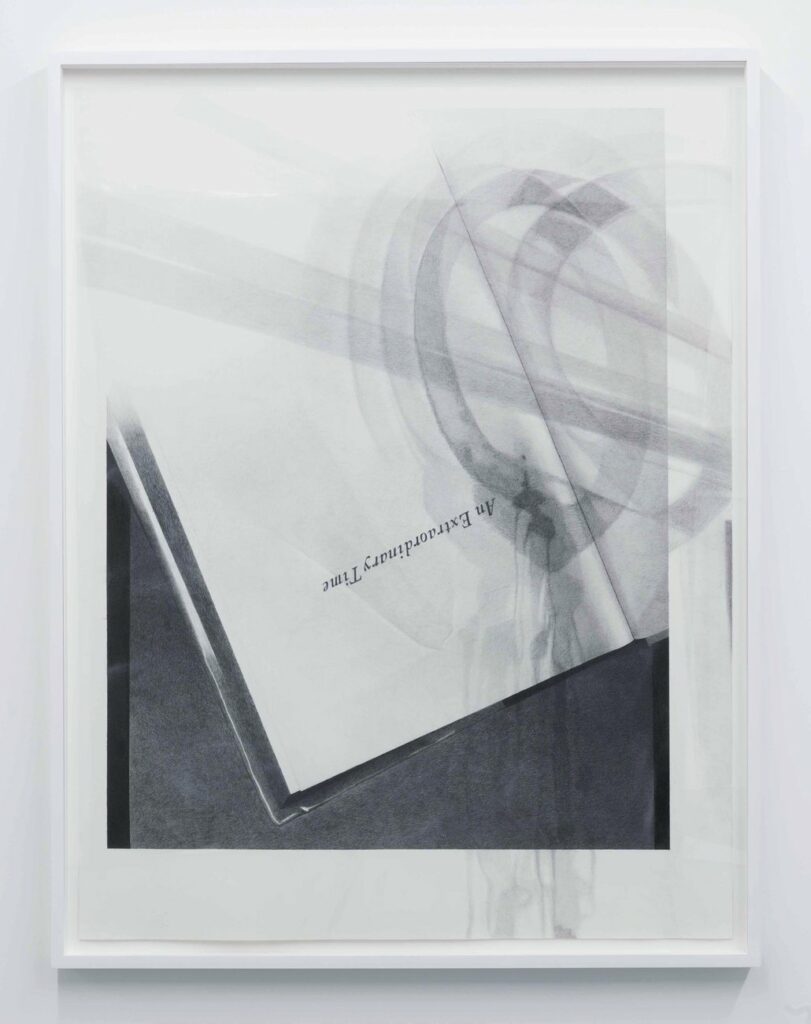

between friends is a layered show. There is the obvious: Morgan and Simpson are friends, and their work looks good together. A shared sensibility runs through the exhibition. Though mostly small scale, the abstract works on paper convey a sense of spaciousness, an aloofness paired with restless experimentation, of working-through and with material languages. All but one of the titles of Morgan’s works begin with the word “Studies:” the process of figuring things out is palpable, even if the details and desired destination (if there is one) remain opaque. A rehearsal of sorts, Studies for ‘Like It is: Extraordinary Togetherness’ orbit around questions of togetherness (is it a state? a process? an action?) and the extraordinary.

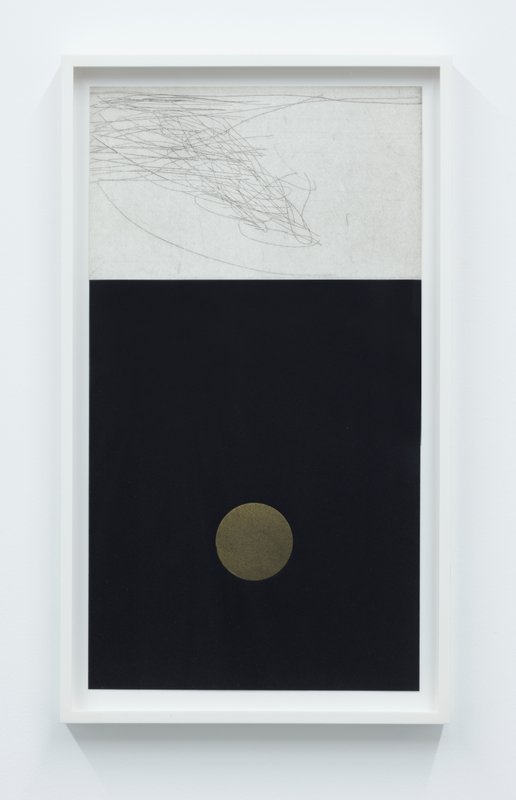

Nyeema Morgan, Studies for ‘Like It Is: Extraordinary Togetherness’, No. 9, 2016. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

Nyeema Morgan, Studies for ‘Like It Is: Extraordinary Togetherness’, No. 22, 2016. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

Nyeema Morgan, Studies for ‘Like It Is: Extraordinary Togetherness’, No. 11, 2016. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

Nyeema Morgan, Studies for ‘Like It Is: Extraordinary Togetherness’, No. 12, 2016. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

Nyeema Morgan, Studies for ‘Like It Is: Extraordinary Togetherness’, No. 2, 2016. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

Morgan’s collages are delicate formal arrangements: in a palette of green, white, and black, the artist grapples with a repertoire of forms—circles act like spotlights amid oblique angles of cut paper; slivers, barely there, drift, unmoored and looking a little lost. “An Extraordinary Time,” reads one of her drawings of an upside-down book page, carefully and only partially covered with an array of smudged pale circles and lines. They look accidental, like the rings left behind by coffee mugs and spills, but are anything but: what if the extraordinary lives and breathes in the ordinary?3 And what if we only realize how the two blend at the very moment when loss transforms once-ordinary togetherness into an extra-ordinary time, just as the realization dawns that a return to what once was is no longer possible?

Loss plays a prominent role in between friends. The two artists lost their mothers in recent years, just as they had children of their own. These profound personal changes took place amid the rise of political unrest and polarization, framed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The presence of loss—personal, generational, communal—requires reckoning with an absence that looms, unspeakable, amid the formerly ordinary. Grief is a liminal state, transformative in its power to undo the persons we thought we were. “Her death, and my giving birth—ruined me, so to speak—in the best possible way,” writes Morgan.4

Death and birth bookend the practice of friendship. When reading what philosophers have to say about friendship, death is a curious constant. In the Politics of Friendship, Jacques Derrida wastes no time to bring up mortality: “Friendship provides numerous advantages…but none is comparable to this unequalled hope, to this ecstasy towards a future which will go beyond death. Because of death, and because of this unique passage beyond life, friendship thus offers us a hope that has nothing in common…with any other.”5 Death does not signal the end of our attachments. In its aftermath, Simpson and Morgan’s year-long correspondence led to the exhibition between friends.

Both mothers are present in their very absence. Two black and white photographs, affixed to the gallery windows, pay tribute to their memory. As you enter, these images act like guardians of a threshold. One photograph shows a Sitka spruce. The tree marks the spot where Simpson scattered the cremated remains of her mother’s body. Next to it, a photograph of a ceramic sculpture by Morgan’s mother, Arlene Burke Morgan. The sculpture, Between Friends (1985), provides the title for the exhibition. Two faces rise from a clay plinth, eyes closed, lips parted in song. It is an image of togetherness, an intimacy forged in the joining of voices and breaths. Can we befriend our mothers? Perhaps once we no longer need them?

Simone Weil, mystic and political activist, pondered what she calls “the miracle” of friendship: “When a human being is in any degree necessary to us, we cannot desire his good unless we cease to desire our own. Where there is necessity, there is constraint and domination. We are in the power of that of which we stand in need, unless we possess it. The central good for every man is the free disposal of himself.”6 Friendship, here, only becomes possible when we are free to choose it. And the question of freedom is fraught, in friendship and elsewhere, especially when it intersects with questions of care.7 An “elective affinity,” friendship tests our sense of self: It “is neither a conventional intimacy, nor a brotherhood or sisterhood, nor a networking opportunity. Rather, it is an elective affinity without finality, a relationship without plot or place in our society, an experience for its own sake.”8 There is much to unpack here. The sovereignty of friendship resists being reduced to a means that serves some end. Lacking a predictable plot and place opens the door to what Leela Gandhi calls “the improvisational politics” of friendship, its “affective cosmopolitanism” that refuses to abide by a “logic of similitude” (that is, the misconception that we can only befriend what resembles us).9 Shared experiences may connect us, or may connect Simpson and Morgan, but what we make of them is a different matter entirely.

Birth, too, plays a role in the literature on friendship, not as a one-time biological event, but as a process of emergence: “We multiply, create, and discover our actual and potential selves, not fall back stubbornly into the claustrophobia of our supposedly ‘true self.’ Friendships are extensions of ourselves into the realm of liminal adventure.”10 As in any adventure, we do not know what’s next. (If we did, would we still be adventuring?) Friendships make us stretch, bend, grow, and improvise with others who endure and elect togetherness, time and again. Thus, we are born in entrusting ourselves to another and, in the process, discover who we might (want to) become: Friendship “thinks me before I even know how to think,” writes Derrida.11 The temporality of friendship, then, is anything but linear: it molds a sense of self in relationship, activates a hope unlike any other for a future, and stubbornly lingers in the wake of loss. “It takes time to do without time,” concludes Derrida laconically; time to trust a friendship to endure, despite constraints of time and distance.12 Extraordinary togetherness, indeed.

One way of looking, then, casts between friends as a dialogue about love and loss. There is no strict separation between the two artists’ works. The only hint of a division arrives as a thin, black line that runs across the entirety of the white walls. It feels less like a horizon line and more like a deliberate bisection of space. The works on paper hang above and below; at times, they cross and thus obscure the dividing line, effectively compromising here and there, mine and yours, but always resting in subtle but unerasable difference. This small gesture seems significant: “The two friends have fully consented to be two and not one, they respect the distance which the fact of being two distinct creatures places between them,” writes Simone Weil. “There is not friendship where distance is not kept and respected.”13 Writing half a century later, Svetlana Boym agrees: “To love a friend is to recognize the difference and estrangement of the other. Friendly love, which is based on asymmetrical reciprocity, demands the recognition of the foreignness at the core of intimacy.”14 Somehow the thin black line conjures this quality of difference respected, of a togetherness that can feel as miraculous as it is strange.

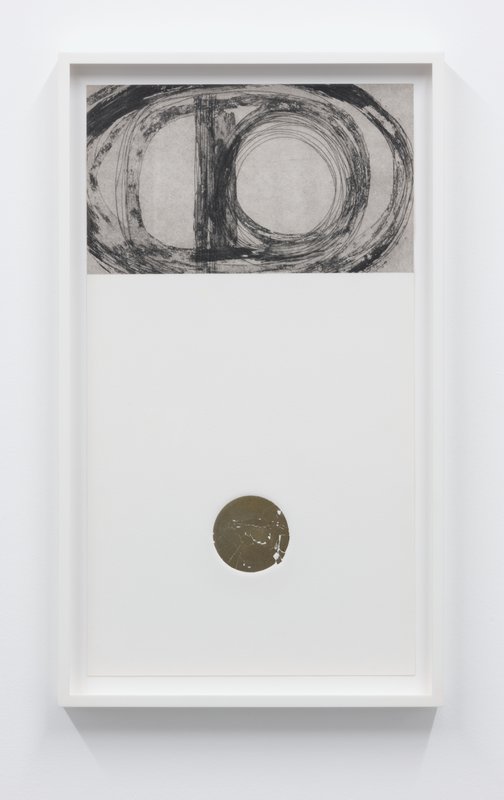

A divided togetherness reappears in Mary Simpson’s art. Most of her two-dimensional works join two paper sheets with archival tape. The diptychs seamlessly juxtapose different forms of mark-making—scratchy thickets of lines next to gilded forms that resemble clothing patterns and fractured orbs. All are named for a phrase from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “Stanzas Written in Dejection, near Naples” (1818), composed in the aftermath of the poet’s one-year old daughter’s death: “purple noon.” The poem ends with “joy in memory” but pits the poet’s despair against the purple noon’s might. Shelley, who drowned in the Mediterranean four years later, comes up in the excerpts from the artists’ correspondence as well. Legend has it that, when his body was cremated on a beach, his heart refused to burn. It had turned to stone, calcified from illness. (There is some debate about whether the organ was his heart, his kidney, or his liver.)

The heart of stone, it is said, can no longer feel. (Though in Greek myth, proud Niobe, ossified, still cries for her slain children.) Simpson turns to geology as metaphor, too. Metamorphic rocks are born under intense heat and pressure; metasomatism chemically alters the molecular make-up of subterranean stone. Torching the delicate table into a black sculpture, she invokes the transformative power of loss, the violence of grief that leaves no stone unturned. The circular marks in Purple Noon result from more crushing pressure. They are the remains of small powder-box mirrors. Simpson inked the mirrors and ran them through an etching press, fracturing them in the process and embedding pieces of glass in the paper. The shattered mirrors look like planetary bodies or strange gemstones whose hairline fissures resemble veins of mineral deposits. But the broken mirrors do more: they signal the end of a recognition.

Mary Simpson, Purple Noon 1, 2021. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

Mary Simpson, Purple Noon 2, 2021. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

Mary Simpson, Purple Noon 3, 2021. Courtesy David Petersen Gallery.

In his essay “On Friendship,” Montaigne describes how the ardent affection for a friend “revealed each to each other right down to the very entrails.” Far from cosmetic surface, the friend-as-mirror reaches for the deep. Derrida builds on Montaigne when he compares “the knowledge we have of each other” to being “equally shared in the glass of a mirror,” a reflection that is “nevertheless autonomous on both sides. …this sliver of mirror is indeed the sign that my friendship reaches towards, and is sustained in, the other.”15 Broken, Mary Simpson’s mirrors speak of the end of such revelation. The survivor no longer shares a reflection with her trusted friend. This survivance, though, distills the core of friendship: “For one does not survive without mourning…surviving is at once the essence, the origin and the possibility, the condition of possibility of friendship; it is the grieved act of loving. This time of surviving thus gives the time of friendship.”16 Deeply personal, between friends does not fetishize grief. Pain remains private. Loss is deeply felt, joy remembered, and situated in the sociopolitical realm. As of November 29, 2022, 6.63 million people have died from COVID-19 globally; 1.09 million in the United States. How do you grieve numbers? You don’t. But in the acute agony of loss, ruined in the best possible way by grief, perhaps there is a possibility to come together, in times ordinary and extraordinary, to protest what, in the words of Amanda Gorman, “just is,” even though it may be far from justice.17 Could friendship offer a path to short-circuit political polarization and entrenched, systemic, far-too-common violence? Leela Gandhi, in her “Manifesto: Anti-Colonial Thought and the Politics of Friendship,” suggests as much. Perhaps, what between friends asks, in the end, is how to turn the marvelous and powerful experience of friendship into a force capable of sparking and sustaining social transformation, of healing, of entrusting—not a state but an action, a choice: a study for elective affinity.

between friends is on view at David Petersen Gallery through December 17, 2022. More information at davidpetersengallery.com.