The Wary Feminist

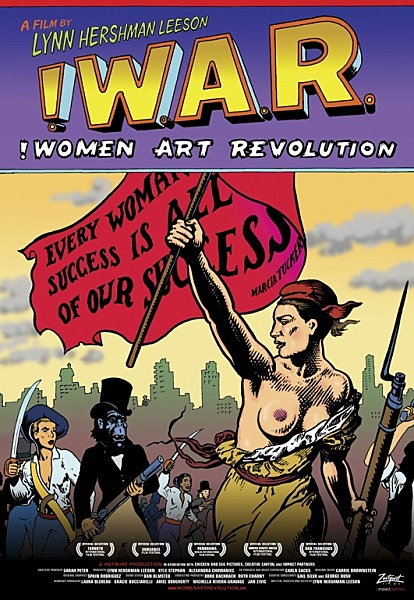

We recently screened !WOMEN ART REVOLUTION for a panel discussion on feminist art with local artists. Miranda Trimmier offers a contrarian's view, making the case for critical ambivalence in lieu of tidy political messages or cathartic storytelling.

I should have been excited to see ¡WOMEN ART REVOLUTION, Lynn Hershman Leeson‘s new documentary on feminist art movements from the 1960s-’80s. Watch the trailer, and it’s clear the film celebrates bold women and fearless artistic experiments, two things I like a lot. I should also have been excited when mnartists and the Walker invited me to watch and discuss !WAR with an accomplished, cross-generational group of women artists and critics: Laurie Van Wieren, Camille Gage, Margaret Pezalla-Granlund, Paige Sweet, and Susannah Schouweiler. Along with boldness and experimentation, I like talking to smart women about art. It should all have been quite simple.

But I wasn’t excited to watch !WAR or to sit down and talk about it. In fact, when the time actually came, I felt wary and uneasy and vaguely annoyed that I’d agreed to do either. I wasn’t quite sure how to unpack this resistance. Immediately, there was the film’s title, with its fanatically positioned exclamation point and militaristic acronym; maybe my wariness also had something to do with that trailer, which, for all its appealing boldness, is irritating in its didactically revolutionary arc. These pre-screening clues promised little in the way of nuance or ambiguity. And there was also the idea that the best way to think through such a movie was to assemble a group of people who’d never met — simply because we were women and artists — and ask us to talk. I just didn’t trust this kind of conversation to lead to something particularly critical or illuminating about feminist art.

My reaction sounds bratty, perhaps — the ungrateful stance of a young woman who can afford to take feminism for granted. In truth, I can’t dismiss that possibility: I am young, and perhaps ungrateful, too, though I try not to be. But I think my uneasiness amounts to more than that. After all, I know an entire history of women artists who are temperamentally oblique and suspicious of unnecessary talk; they’ve taught me most of what I know about thinking, writing, and making art. And I don’t know where women like this fit in a film like !WAR, or discussions of feminist art more generally. Ambivalent voices aren’t easily assimilable to dialogues guided by direct messages and an unexamined faith in talk.

There may not be easy answers, but I have to start with this question, in part because I don’t know a better way to begin: When we talk about feminist art, where does uneasiness fit? And wariness or annoyance? Ambivalence and silence? I ask because I imagine there are other women like me, and I’d truly like for us to be more excited to join the conversation.

When we talk about feminist art, where does uneasiness fit? And wariness or annoyance? Ambivalence and silence?

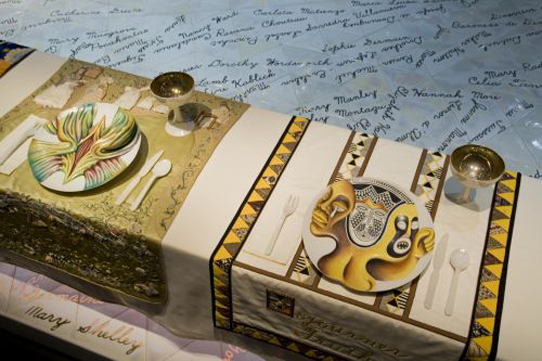

If you’ve seen Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party, you know the piece is not subtle: a giant triangular table set for 39 famous feminists with 39 vulva-shaped plates atop 39 floridly embroidered placemats. Chicago and The Party occupy a considerable portion of !WAR‘s attention — a significant fact in a film that covers dozens of other artists without ever really lingering on one. Whether or not it was Hershman’s intention, from the film’s persistent attention, a viewer could easily read Chicago as a feminist artist par excellence and The Dinner Party as a summation of feminist art movements. For her part, Chicago seems to have been attempting just this sort of universalizing gesture: she describes the piece in grand terms, as her effort to imagine a feminist society. But I find this feminism — and the art it inspires — narrow and off-putting. It is too certain in its politics, too totalizing in its tone, too one-dimensional in its representation of women’s experiences. The Dinner Party is exactly the sort of work that makes me wary of feminist art.

There’s a scene in !WAR, though, that encourages me to forgive Chicago for her heavy-handedness and Hershman for spending so much time documenting it. After shots of The Dinner Party‘s opening night, which was attended by hundreds of giddy supporters, Hershman cuts to a telling counterpoint: a session at the U.S. House of Representatives, where a group of male legislators are debating the work’s merits. Specifically, they don’t see any; they are incensed at what they deem its use of “pornographic” imagery; they would prefer that the piece didn’t exist, or, short of this, for no one to see it. And they had the power to make just that happen. This congressional debate accompanied a 1990 vote that would have provided the funding for the University of the District of Columbia to buy The Dinner Party and provide it a permanent home; legislators ultimately blocked the sale. Given this political climate, ham-fisted or not, I find it far harder to dismiss Chicago’s work or the importance of paying attention to it.

As powerful as the congressional scene is, though, it polarizes the conversations we can have about The Dinner Party. The analysis becomes glib, pitting supporters against detractors; it’s easy to overlook the fact that the piece’s sympathizers might also have problems with it. As Laurie Van Wieren (who shared studio space with Chicago while she worked on the piece) told us, the artists in Chicago’s circle understood the work’s cultural timeliness, and were accordingly excited and supportive — but not uncritically so. Even at that fraught political moment, some of them watched her pulling vaginal plates off the pottery wheel and thought, Must we?

!WAR doesn’t really know what to do with these more ambiguous kinds of responses, so it largely neglects them. It strikes me that this often happens when we discuss feminist art. Ambivalence — about what feminist art should do, about how we should measure its value and support for the artists making it — gets ignored, I suspect, because it is difficult to narrate.

Without directly designating it as such, the film does actually examine some practices in feminist art that might inspire more complex, if ambivalent dialogues. Like Chicago, most of the artists featured in the film are interested in women’s bodies. For many of them, bodies serve as more than just metaphors in their finished pieces; they act as subject, medium, and producer in works that emphasize process and experimentation. These artists have played with fragile corporeal materials like hair and blood, staged performative works about sex, violence, and domesticity, and tested non-hierarchical collaborative models for sharing labor between projects. The art they’ve produced may not always be as politically expedient as The Dinner Party, but it allows a woman’s body to mean many things: a site of oppression, a place of pleasure, a means to an end, and an active, productive force — all at once and in constantly shifting proportions.

For a wary woman, these creative experiments offer one promising entryway into feminist art, a place where a more ambivalent, but also more fruitful dialogue might begin.

Conversations about feminist art often err on the side of inclusion at the expense of meaningful critical elaboration, which is lost in the generalized impulse to share, to talk, and to correct the record.

!WAR opens with a dedication to the secret history of feminist art, which sets a tone that recurs throughout the film, which makes frequent reference to silences around women’s creative work and its omission from established museums and historical accounts. Hershman clearly seeks to correct institutional and historical traditions that have tended to ignore the contributions of women artists. !WAR accordingly spends a good chunk of its time enumerating artists’ experiences, giving it a jumpy, diffuse feel. Incidentally, the 90-minute film represents just a small portion of the material Hershman collected: she gathered more than 12,000 hours of footage while working on the project, and has set up a website, RAW/WAR, to allow women artists to add their own stories. But Hershman never offers a fully developed analysis of these experiments; instead, she leaves the viewer to extrapolate their own from the meandering structure of the documentary.

I’m not immune to the simple power of storytelling, and I don’t want to discount its importance. In fact, I’m tempted to write about our panel’s post-!WAR dialogue in similar fashion. I find myself wanting to report that, in a gross and perfect bit of timing, Paige Sweet got hit on by our discussion group’s restaurant host; or, tell you about the time Camille Gage’s all-women punk band auditioned for Star Search and was asked to trade their usual denim and leather for evening gowns; I could repeat Susannah Schouweiler’s droll characterization of early motherhood as a process of learning to be “an effective milk-delivery device”; or, reveal the reason why Margaret Pezalla-Granlund started a project that eventually produced hundreds of small watercolors: when her kids were young, those pieces were the only things she could produce in the limited time and spaces available to her while caring for her children.

Each of these stories, alone, contains a wealth of information about women artists’ relationships to their bodies, creative opportunities, family, and time. When too many of these stories are placed next to one another, though, it’s difficult to maintain a critical through-line. There is only so much room for intelligent elaboration in a ninety-minute documentary or a two thousand-word essay. Conversations about feminist art often err on the side of inclusion at the expense of this critical elaboration, which is lost in the generalized impulse to share, to talk, and to correct the record. The resulting conversations we have about such work, as a result, tend to feel dissatisfying and unfocused.

Of course, this tendency in feminist art and criticism — to err on the side of inclusion — arises out of a very real lack of visibility for women artists. That is, Hershman has good reason to dwell on the omissions and silences: feminist art movements in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s developed, in part, because major museums weren’t really showing women artists, hiring women curators, or paying attention to women critics. Much of the art and activism of the period necessarily took up the task of dealing with that lack. The Dinner Party, for instance, speaks explicitly to the problem; the piece’s didactic tone probably stems in part from a desire to respond to it quickly and decisively. For her part, Hershman uses !Women Art Revolution both to document the historical circumstances that necessitated a focus on storytelling in feminist art and criticism, and to make the case that we still need to talk more about women’s art. And she’s right. In the discussion after our panel of local artists screened !WAR, most of us admitted that even we hadn’t heard of many of the artists profiled in the film.

Still, I worry about valuing talk, any talk, in a conversation that isn’t balanced by judicious filtering and critique. Such talk can quickly become mush, and, besides alienating people like me from the conversation, it also risks confusing a set of means with an end.

Conversations about feminist art often err on the side of inclusion at the expense of meaningful critical elaboration, which is lost in the generalized impulse to share, to talk, and to correct the record.

There is an invisible connecting thread in this essay, an obvious subtext which I’ve failed to address: money and resources. This essay’s questions — about political expediency and institutional and historical omissions — link intimately with questions about who is able to create a sustainable life of art-making. There’s a sad scene in !WAR in which a woman who helped run an experimental women’s exhibition space looks straight at the camera, with tears in her eyes, and asks what more she and her collaborators could have accomplished if they’d had better access to money.

It’s a useful reminder, and one that prompts me to temper my more uncharitable feelings toward feminist art and criticism. To strike a loud, didactic tone, or to focus on unfiltered storytelling in the name of correcting the record — these decisions aren’t necessarily blithe or naive. They may be well-considered tactical positions. But my wariness and ambivalence in the face of such positions are well-considered, too, and in the end, I don’t think those mixed feelings should be dismissed out of hand. Taken seriously, they might serve to expand and sharpen our ideas about what feminist art can do – how it can look, what it can mean, and how it can create better opportunities for women artists. Could we imagine a conversation about the artistic and political efficacy of critical ambivalence, say, or the economic strategy behind a fierce feminist silence? These questions aren’t easy to unpack, but they might produce richer conversations about feminist art, conversations in which I’d be more excited to take part.

Noted event details: Lynn Hershman Leeson’s documentary !Women Art Revolution showed at the Walker Art Center in late November, as part of the “And Yet She Moves: Reviewing Feminist Cinema” series. The film is currently on screens around the country. Visit the !WAR website to find a showing near you.

Two of the panelists mentioned in the essay above, Margaret Pezalla-Granlund and Camille Gage, offered their own personal responses to Hershman’s film for the Walker’s Film/Video Blog.