A Voice So Absurdly Truthful

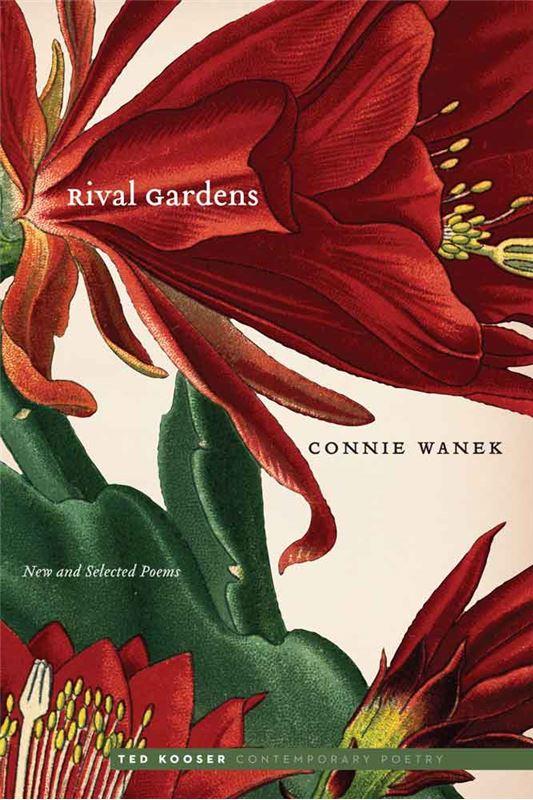

Tim Nolan reviews Connie Wanek’s latest collection of poetry, "Rival Gardens: New and Selected Poems" from University of Nebraska Press.

A short poem by Harvey Shapiro provides the benediction for this review of Connie Wanek’s new collection, Rival Gardens. Here it is in full:

“The Uses of Poetry”

This was a day when I did nothing

aside from reading the newspaper,

taking both breakfast and lunch by myself

in the kitchen, dozing after lunch

until the middle of the afternoon. Then

I read one poem by Zbigniew Herbert

in which he thanked God for the many beautiful

things in the world, in a voice so absurdly

truthful, the entire wrecked day was redeemed.[1]

What is it about “a voice so absurdly truthful” that can redeem a wrecked day? After all the chatter about poetry, from Aristotle to Eliot, I have been thinking about first principles, maybe a unified theory of what makes a poem live and breathe, and thereby makes it useful to the reader or listener. The “absurd truth” of the poet’s voice seems to me a finer distinction than most. We read poems to find this truth. We recognize greatness in poets who are also searching for this truth. Our own sense of truth in what we see and feel and think is confirmed in the presence, within ear-range, of a poet available to this voice. The subject matters of poems, the particular turns of phrase, the narrative arc of a poem or a collection of poems — these all recede in importance. We are looking and listening for the voice, and the voice is absurd because it is so unlikely that the poet and the reader or listener could meet, could somehow share, briefly, the same insights, the same absurd truths.

Over the years, Connie Wanek’s poems have regularly redeemed my wrecked days. She has a light and free touch with our American English. She can make a poem out of anything — a head of garlic that is like “a hobo’s bundle;” a rag that once was a piece of a blue dress, now used to dust the piano and gone gray; the game of Monopoly, in which one person ends up owning all the hotels and railroads “every teaspoon in the dining car, every spike driven into the planks by immigrants.” Wanek’s particular observations of objects — skim milk, a radish, a peach, an accordion — arise in the great tradition of the French prose poet, Francis Ponge. Like Ponge, Wanek allows the objects to work upon her, to become an occasion for exercising her unique voice, which is at once sly, wise, abrupt, philosophical, weary, joyous, hilarious. Put more directly, she brings all of herself to the occasion of the poem. The poet’s confidence gives the reader confidence in turn, and in the way of all artistic mysteries, that exchange is inspiring.

Who else but Connie Wanek could make these observations and draw these profound conclusions from such a quick little poem?

“Garden Gloves”

By August we hardly know them.

Work made them ours alone.

Tugged on, often too late,

they tried to be braver than they felt.But isn’t that exactly

what we do for each other?

Let me hold your hands now.

Let the harm come to me.

_____________________________________

Wanek allows the objects to work upon her, to become an occasion for exercising her unique voice, which is at once sly, wise, abrupt, philosophical, weary, joyous, hilarious. Put more directly, she brings all of herself to the occasion of the poem.

_____________________________________

The garden, its inhabitants and visitors, operates as an extended metaphor in Wanek’s work, as do the City of Duluth and Lake Superior, the wild woods, snow, the moose wandering down from the hills above the city. There is a bracing wind off the big lake that somehow swirls around these poems, and a joyful breathlessness, coming in from the cold to warm up in the domestic close. Wanek writes honestly and directly about everything that comes to her, including the death of her father, the acute loneliness of raising children and having them grow up and move on, and the wider working out of religious belief in the changing garden, the evolving seasons, the incessant coming and going.

Wanek has a remarkable ability to begin poems in unlikely places. Her angle of entry into a poem is always surprising, but exactly right. The poem “On the Death of My Father” begins:

He died at different times in different places.

In Wales he died tomorrow,

which doesn’t mean his death was preventable.

There is absurd and comical truth here, but one that still contains the underlying grief, a kind of tough and clear-headed truth that reassures. The same poem ends:

I once was found but now I’m lost.

I could see, but now I’m blind.

An important part of a poem’s strategy is the getting from here to there, from beginning to end. The example above shows the impressive range of the poet’s journey in grief within a single poem, from humorous speculation to undaunted sadness.

This book is beautiful in every respect — the poems themselves seem to glow on the page; the cover is vivid and deep in its imagery and color. The cover paper is soft, as if the book, while it is brand new, has already been lovingly handled many times. Former U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser provides an interesting and fulsome introduction.

I have come to judge music, poetry, art in general, on whether I am inspired by it. Does my interaction with the work cause me to want to make something myself? So — Bob Dylan, Vincent Van Gogh, Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Shakespeare. They all inspire me. Ditto Connie Wanek.

Related events and information:

Connie Wanek will read from Rival Gardens: New and Selected Poems in a celebration of the publication on Monday, April 18, 2016, at 7:00 pm, as part of the Literary Witnesses program, Plymouth Congregational Church, Minneapolis (Nicollet and Franklin). Author Charles Baxter will offer an introduction, and a reception and book signing will follow the reading, co-sponsored by Rain Taxi Review of Books and The Loft Literary Center.

Tim Nolan is a lawyer and poet in Minneapolis. He has an M.F.A. from Columbia University. His three books of poems are all from New Rivers Press —The Sound of It (2008), And Then (2012), and The Field (2016).

[1] Harvey Shapiro, The Sights Along the Harbor: New and Collected Poems, Wesleyan University Press, 2006.