The Silent Chorus of Limestone: Non-human Witnesses to Intimacy, Creation, and Destruction in Settler Colonialism

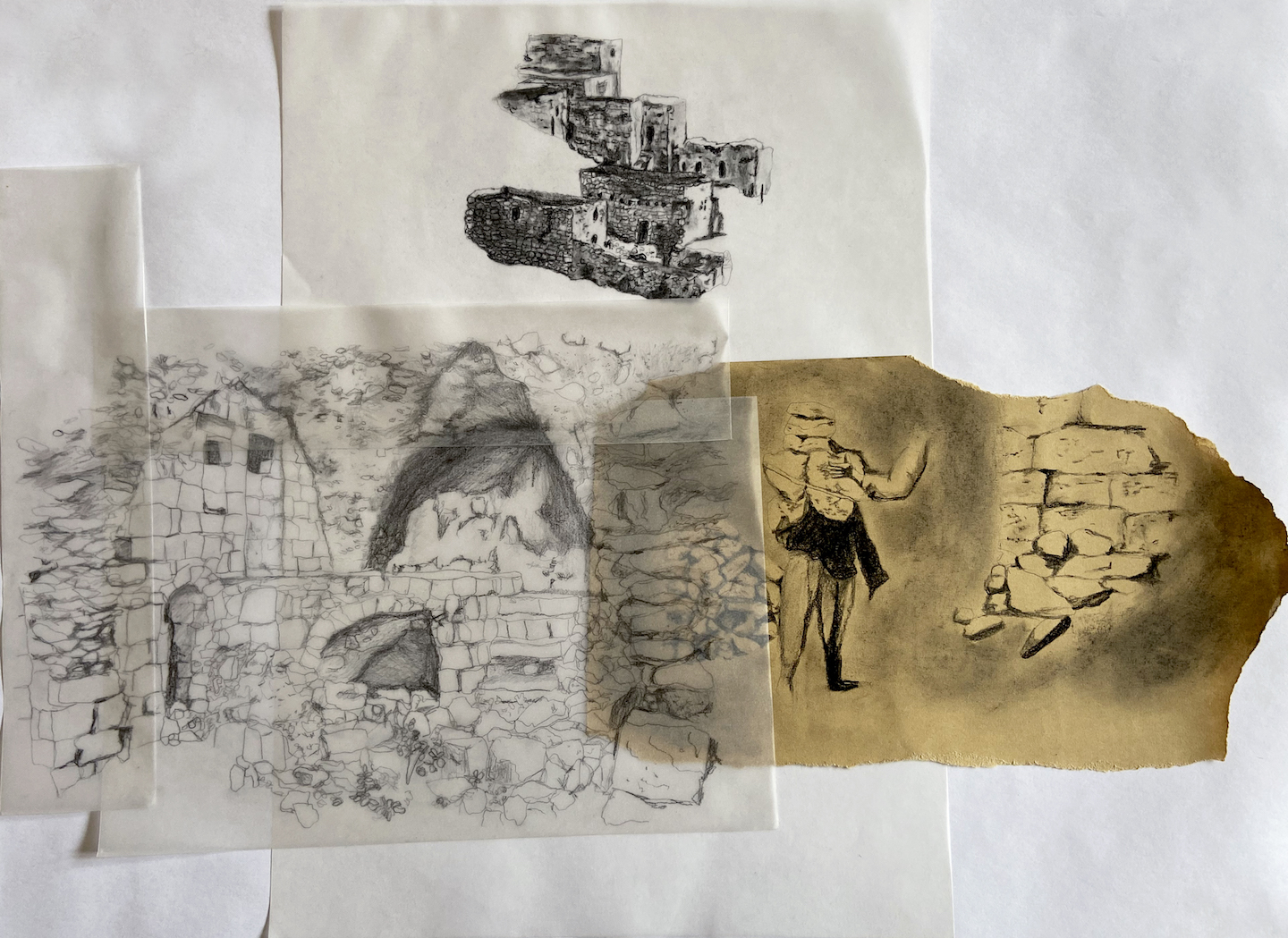

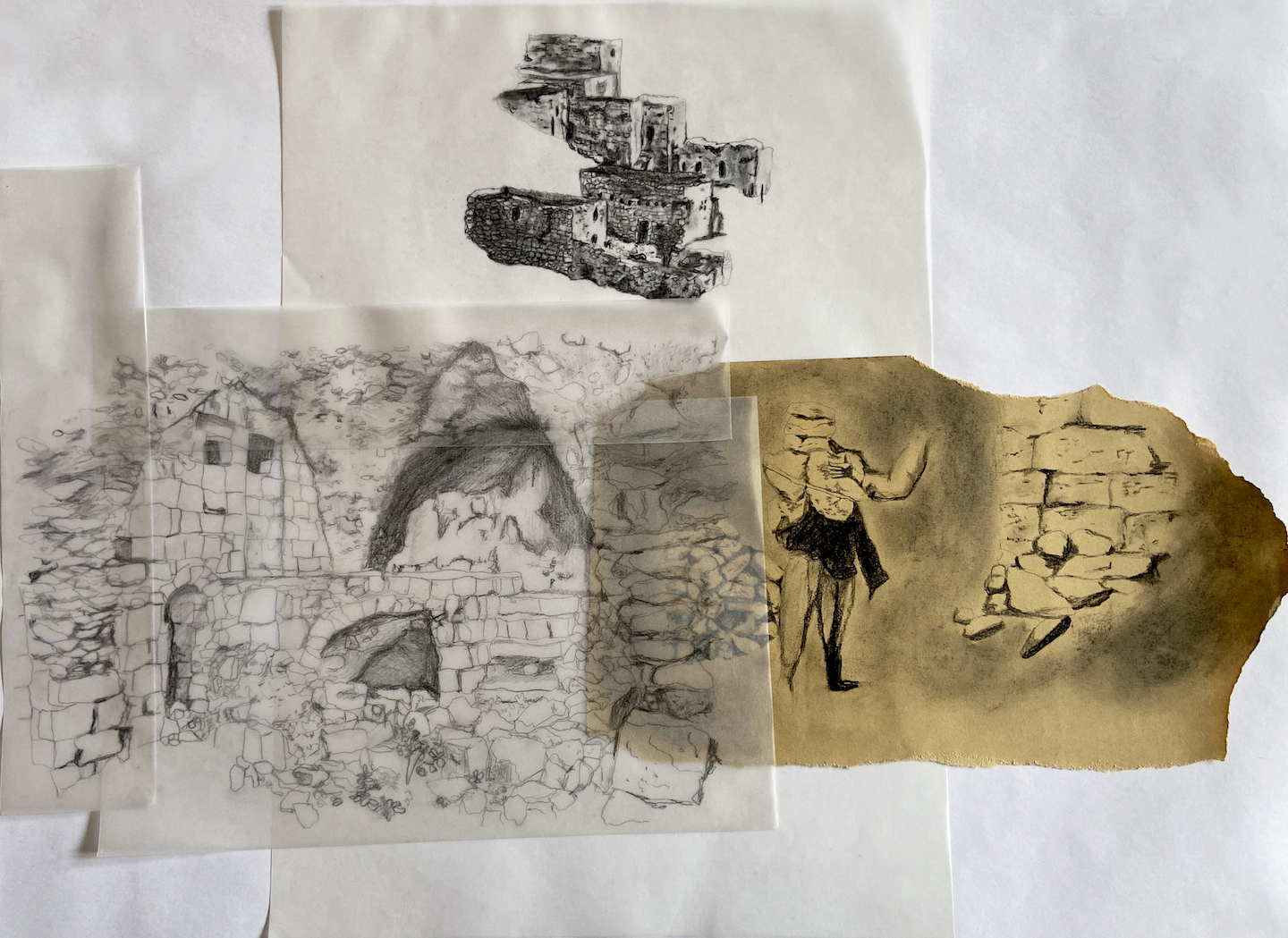

Interdisciplinary artist Lamia Abukhadra delivers a meditation on settler colonial violence that cuts between multiple perspectives—giving voice to limestone “witness stones” as a temporary archive, material witness, and intimate participant in the creation and destruction of Palestinian life.

Every rock has a name in Kamal Aljafari’s Recollection.

In the beginning, the absence feels abrupt. The foregrounded figures are there and then they’re not. Deliberately disappeared, they are made not to be there. The digital erasure leaves behind only the background and the characters who dwell there: minor figures.1

You are the viewer and the camera.

A flash of wake in the ocean. Cut. A blurred grouping of stone structures in the near distance: you are about to arrive in a city by the sea. At the docks, you look up and see the tops of buildings and villas that at some point may have been grand. Cut.

You are walking through the city in the Manshiyya and Ajami neighborhoods, but there are no people. Only structures. Limestone, cement, wire, and metal make up a place that has lost its inhabitants. Where is everyone? The city is run down. Walls are crumbling, paint is chipping, tires pile on the side of the road. The Jaffa you see is a city in ruin, a place haunted by its denizens,2 those figures hovering in the background. Somehow you know the city was deliberately destroyed. You hear footsteps, an occasional distant clatter, an indiscernible noise; always, the sea is roaring.

The sounds come from microphones, placed inside interior walls and deep in the ocean, where pieces of Jaffa were discarded by the Tel Aviv municipality.3 You realize that though this film has no protagonists, no foregrounded bodies or forms, the ruins and figures intentionally left in the background are the main characters. Barely there, the people peek from behind columns or through windows. Sometimes they are just passing through frames, like they were not meant to be there—both in the imagined and the real geopolitical sense, both included and erased as a backdrop to the Israeli cinematic settler-colonial imaginary.

Cut to an alleyway of old stone houses. Hold. Zoom to five figures sitting on a balcony at the top of the frame. They are almost invisible until the camera emphasizes their presence. Their faces, too small to register digitally or on film, remain a blur. Cut again. From behind the corner of a light pink house with brown shutters, someone is watching furtively. You repeat panning onto this person over and over. You must see them, acknowledge they were there for a split second. As if in a dream or a muddled memory, you return to cement stairs, a red house, some people gathered under a balcony, a man in a yellow shirt. Halfway through the thirty-third minute, a man crosses a street; he doesn’t know he is being filmed. The sequence of crossing is repeated nearly a dozen times in the next few minutes. Throughout, the walls, tiles, alleyways, rusted gates, large stone piles, and rubble loom. Characters in their own right, they too are part of re-collecting Jaffa.

The credits of the film begin with a series of scrolling anecdotes. Each names a marginal character, identifies a structure or an alleyway, tells their stories. Aljfari knows the people and places intimately from growing up and living in Jaffa. He stumbled upon the footage while watching sensationalist Israeli films set there. The man in the thirty-third minute is his uncle, a phantom who accidentally left a trace in an Israeli portrait of the city.

My uncle Mahmoud walking in Ajami neighborhood;

it was probably a Sunday morning

on his way back to the hospital.

…

The grand red house overlooking the sea

is the house where Ibrahim Bilbesi

and his son Hussein, my grandfather,

sought shelter after the war.

They stayed for two months,

until the army came and forced them to leave.

My mother was born in the house with the cement stairs.4

Aljfari does not credit the source films for the footage he altered, as they do not witness Jaffa. They only occupy the space cinematically. Instead, he names the walls, tiles, and stones left behind. Half destroyed, they bear witness to intimate, terrifying, and quotidian moments in the lives of Labibe, Turnisa, Ahmad Farraj, Abu George Shibli, and many others; and to the ongoing destruction and occupation of Jaffa. Aljafari un-silences their chorus and makes their presence felt, finds a way for us to listen.

Fragments on Limestone

In the Levant, the ancient practice of placing a large stone upright served to mark the relationships and agreements between two parties, to grieve or commemorate an event, and to worship deities. “In this position it served as a marker, jogging the memory. It would arrest the attention of the on-looker because it stood in a position it would not take naturally from gravity alone; only purposeful human activity could accomplish such ‘setting up.’”5 Confrontational, the stones meant to absorb on-lookers in a specific narrative, as if the setting up of a stone mirrored writing in second person: you were hailed by the stone. In Palestine specifically, standing stones were not inscribed.6 Their poetic marking of space was based on memory and connection to a place or moment, embedded within an ethos and understanding of land.

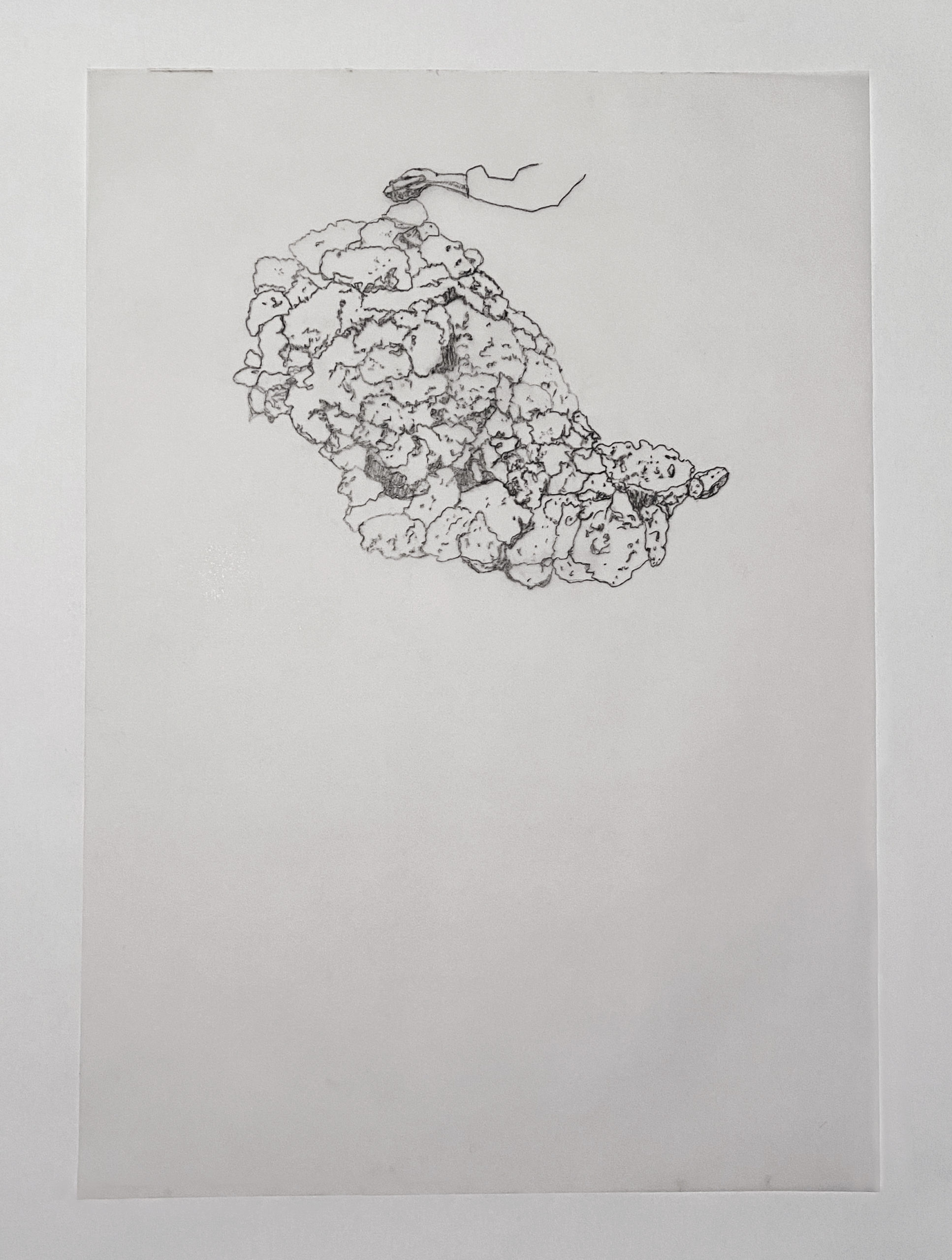

Recorded as recently as the 20th century, the practice of using stone to trigger memory and poetic demarcation of space evolved into the stacking of individual handheld stones, almost always limestone, into mounds. The individual stones are called witness stones, from the Arabic word mashahid, the place from which something is seen or the place where a pilgrim testifies his unity to God.7 In Islam, Muslims may ask animals, plants, or stones to testify on their behalf on the day of judgment.8 The limestone stacks along roads and on top of hills formed a visual network, believed to be protective in a landscape inhabited by jinn and evil spirits. Later, this visual network came to symbolize national identity and belonging.9

To know the meaning of the mounds, one must already have an intimate bond with the resident community. The act of stacking a stone is both individual and collective, intimate and quotidian, permanently inside a stone’s “memory” and part of a fragile, impermanent structure. It is an act of recording, a temporary archive made up of minor figures and moments.

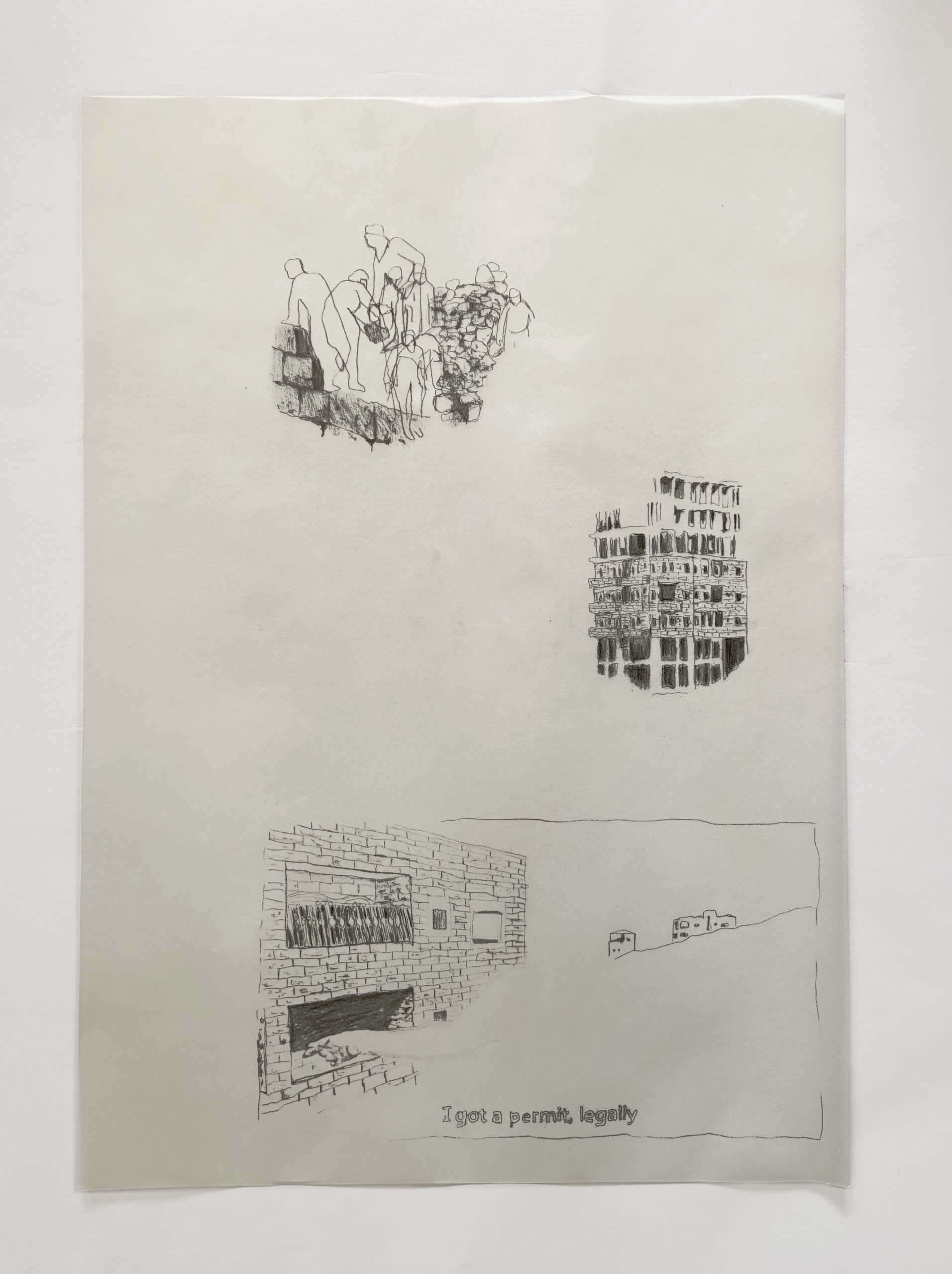

Traditionally and currently, most Palestinians are physically involved in building their homes: they put the bricks, often limestone, in place themselves.10 Early Zionist settlers replaced the traditional stone with cement: a hallmark of the new colonial Israeli aesthetic, embodying the perceived modernity the settlers were bringing to the region. Though, with the recent nationalization of archeology and religion in Israel, the once-shunned limestone has turned into a popular construction material in Israeli settlements: limestone cladding, six centimeters thick, decorates the façades of identical illegal settlement houses in the Occupied West Bank.11

Limestone is the minor figure that remains throughout major moments in Palestinian history and geopolitics, a material witness who intimately participates in the creation and destruction of Palestinian life.

What is the language of stone?

Minor Figures

We feel your warmth against us

We come from you: organic matter, mineralized under high pressure.

You gather us, layer us on top of each other in different formations. You have been doing so for years, centuries, maybe millennia. You learned how to cut us, expertly, before you piled us into intricate geometries; you stuck us together, and so together we grew high enough to make yellow-white-grey hollow domes and cubes. You left openings in the structures you assembled from us, so you could go inside, dwell there, be together in the space we held for you. You called it making home.

Inside, you would keep yourself warm, hold the hand of your beloved, eat steaming bread; protected from evil spirits. Sometimes you would nervously pace, and other times your chest tightened and tears pricked from biting words. We heard your heart pound as you awoke suddenly from nightmares or thunder, saw you crumpled with a stomach ache, laugh as you gave chase, cheeks flush as you embraced in flickering light, stay awake until morning talking. We watched you part ways and left with a gaping hole. You say all this is mundane.

We feel it all; we feel your warmth against us.

Nearby, on hills and along roads, you built us into mounds. One by one, you added one of us— one by one. You asked us to witness, to intercede on your behalf, to mark. We sit atop one another—sometimes four or five of us, sometimes hundreds—and behold your piety, your grief, your fears, your ties, your sickness, your inheritance; مشاهد. We feel it all, your memories gathered together, moments built with supple hands. Here, holding knowledge and not space: a different type of life. We are warm but soberly so.

“You are a woman and I am a woman and you protect womankind,” we once heard you say, as you laid us on top of each other. We remember. We are but minor figures.

Crushed and ground to slurry

You dig us out in such haste and leave behind large, unfillable pits. Mere shards, we are crushed and crushed again: recirculated, fed into machines, and crushed once more until we are but particles. Reduced to powder, we are mixed and wet and poured into formations. Dried and stuck together, you hoist us on cranes, use us to build towers in the name of progress. Perhaps they will reach the heavens. Stacked, our mutilated bodies cover and erase, suffocate and expand ever outwards. Did you know liquid flows across planes much faster than stone? We feel less these days. Can you feel it too? Crushed and ground slurry. Hardened grey puddles.

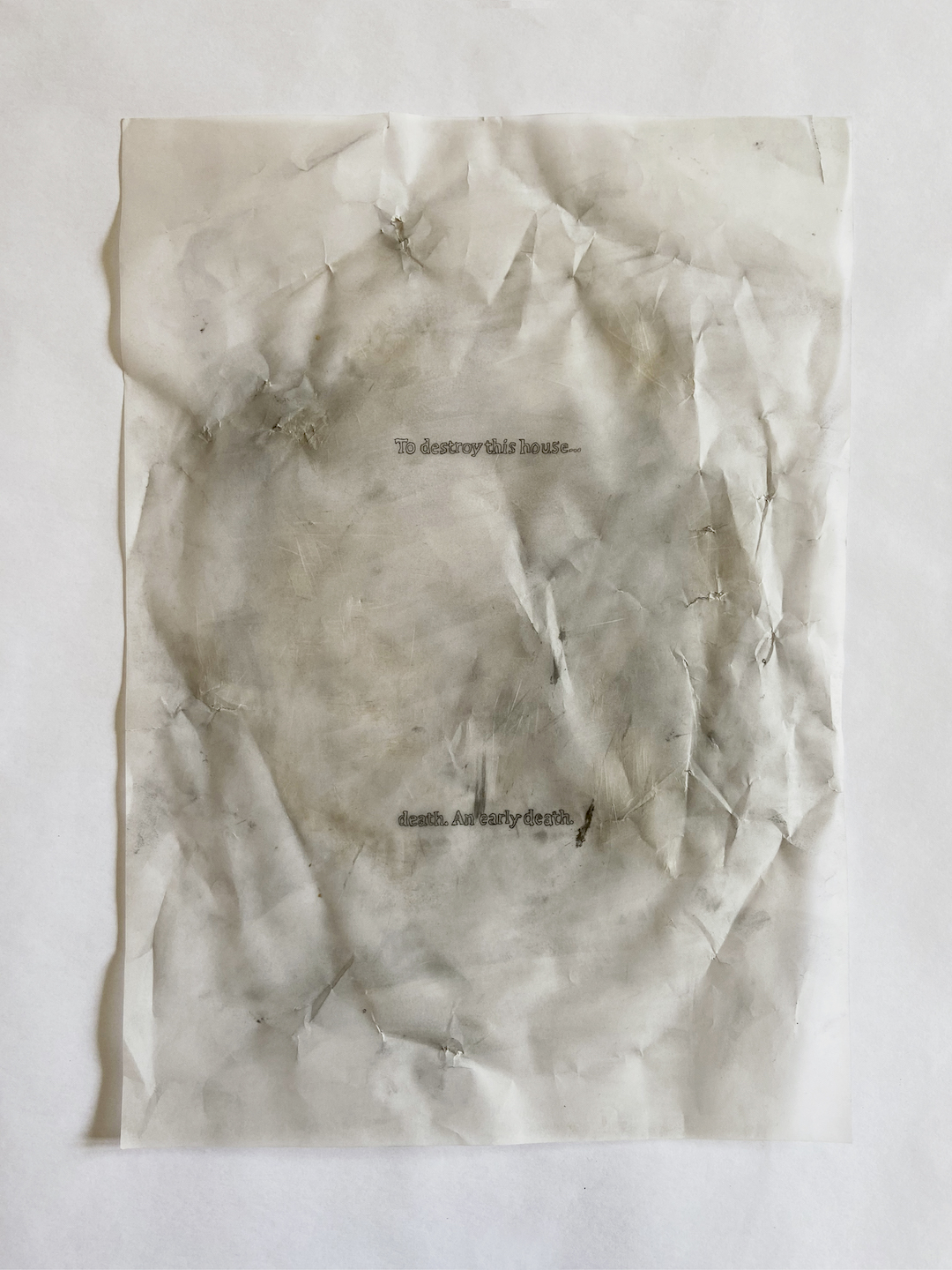

A wall and a lie

Our larger pieces? You have been told to slice us into thin, six-centimeter slabs. As cladding, we cover the outsides of grey expanses. We become part of a façade in that we are a wall and a lie. The walls comprise groups of uniform boxes that carve hillsides. Holes and ruins gape in the hillsides, made to look like they have always been there, a divine presence in an empty place. So many master-planned interruptions. But you were here before they called the land empty; we remember. Now, from a distance, behind fences and invisible lines, you see the lie and it breaks your heart: yellow-white-grey pebbles broken under high pressure. Trapped in pits and ruins, we are forced to live amnesiacally on top of gaping holes. But we, your recollections, remember.

And we did

“Oh stones, witness that I believe and say,” and we did.

That night, you dreamt that on the judgment day you were tried and found to be a sinner and sent to hell. As you approached the first gate of hell we blocked the entrance. All the angels of the lower world were unable to remove this obstacle. The same thing happened at every one of the seven gates of hell. You were brought back to the heavenly judge, who allowed you to enter heaven since the stones had borne witness to your favor.

You feel you are flirting

Some flirt with women, but sometimes you feel you are flirting with the stones.

“They threw the homes they destroyed into the sea. But every year, in the winter, when the sea rises, it throws part of these homes back on to the shore. The Tel Aviv municipality collects them, throws them back but the ruins return. Every year the sea brings them back.”12

Elsewhere: the pattern

Wanagiyata (Spirit Island) was erased: mined away for the construction of the now-defunct Upper St. Anthony Lock and Dam, removed from the Mississippi River between the mid 1860’s and 1960.13 The island had a cap of valuable Platteville limestone, a material heavily used in the early rapid development of the Twin Cities. The stone was quarried to build early settler colonial infrastructure: roads, bridges, factories, and homes along the river.

Andrea Carlson imagines that the island’s limestone is “now fixed into nearby buildings in Minneapolis, perhaps in the Nicollet Island Inn. Maybe pieces of it are in the Stone Arch Bridge, which runs just upriver from where the island once was. Pieces of it may lie on the river’s shore…[or] may now make up the walls of adjacent mills, such as Pillsbury A-Mill.” Downriver, Fort Snelling, where over a thousand Dakota were held in a concentration camp in 1862-63, and where the Minnesota river joins the Mississippi at the sacred Bdote, is built from the Platteville limestone formations it rests on.14

You see the pattern: the removal of sacred stone in the name of industrial progress; structures erected from willful and violent acts of erasure.

Settler colonialism remains conspicuously embedded in the sociopolitical framework of the Twin Cities. Any Minneapolis resident will have noticed how rapidly the city has gentrified in the last decade, how homeless populations and tent cities grow while city blocks are demolished to make room for more luxury housing. Limestone quarries in southern Minnesota mine and crush stone for aggregate,15 an ingredient in the concrete used in the rapid, unethical development of Minneapolis.

I see the pattern. And I wonder what the chorus of the witness stones in Minneapolis sounds like. How we can listen for it more closely?

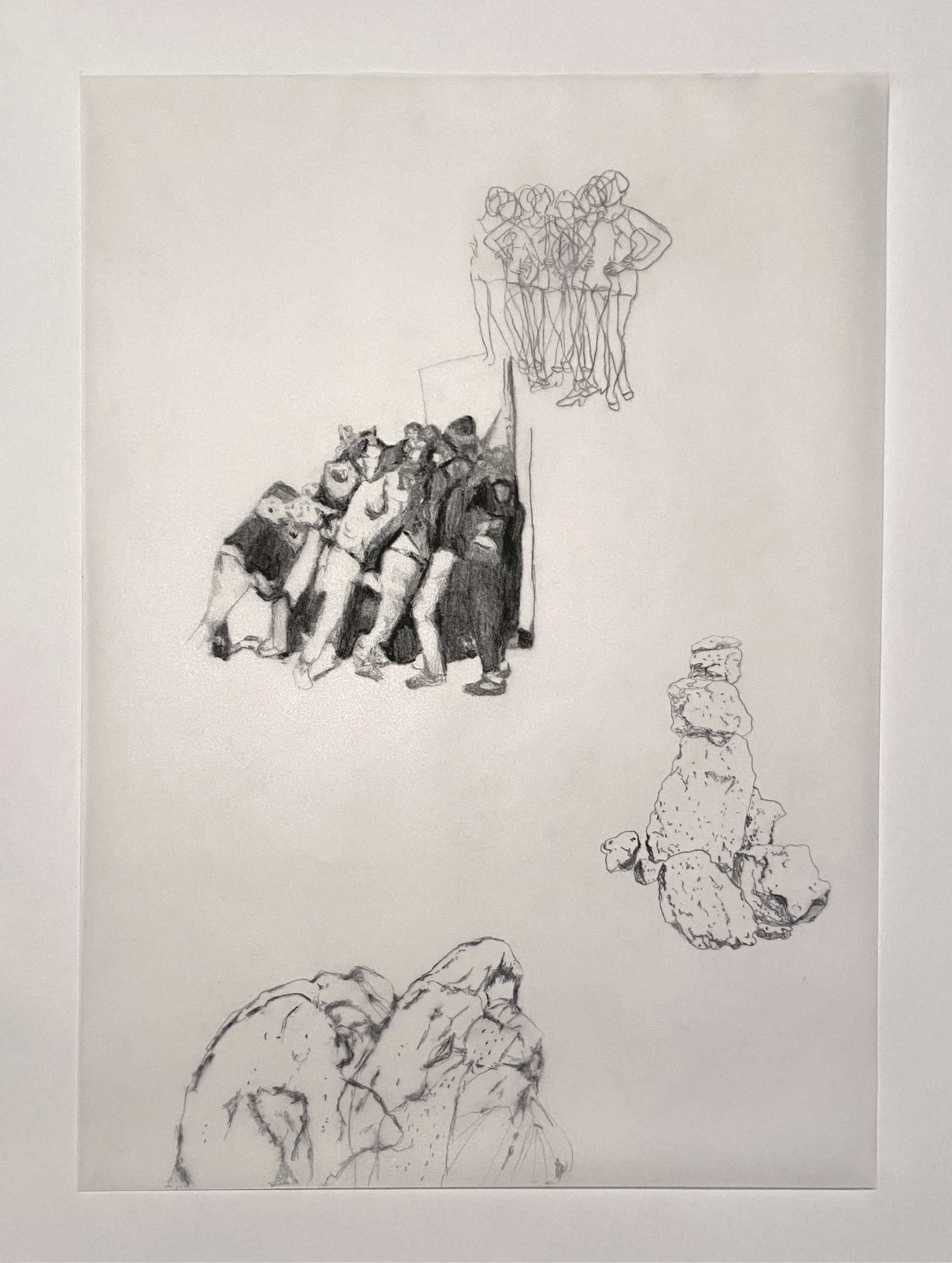

12 to 16 bodies

You are coughing. You have been unable to stop coughing since the canister landed in the living room. You think they threw it in through the window, now barricaded, closest to the front door.

The canister rolled past you across the tiled floor and lodged itself underneath a brown leathery couch, one of the only pieces of furniture left in the house. Smoke in your nostrils, your throat, your eyes. You smell pepper and burnt plastic. Tear gas is permeating every cubic meter of the house: creeping under the bare mattresses, into hurriedly emptied kitchen cabinets, between couch cushions. Your heart is beating fast, you can’t seem to take a deep breath, you can’t see. Your eyes are streaming. You are almost retching, but you cannot retch. Instead you yell and you push, and you lift the shirt you are wearing over your nose and mouth, leaving your stomach exposed. You press your body against the wooden surface with all of your strength. You are one of 12 to 16 people pressed against the door of this house, your good friend’s house. So close together. You throw the whole weight of your body against someone else’s body who is pressed against the door, and someone else throws their weight against your body.

Everyone around you is coughing and retching and yelling words of encouragement and pressing against the door. “!يلايلاااا ,اللهاكبر,اللهاكبر,اللهاكبر,اللهاكبر” The words turn into screams, which turn into gags as the effect of the tear gas intensifies. Adrenaline pumps through your veins. The only thing you can hear is coughing and pounding on the door. You think to yourself that this could have been a very peaceful night. You are 12 to 16 pressed together in defending this house from destruction. The destruction of your friend’s, your neighbor’s, and/or your relative’s home. 12 to 16 bodies piled against a door, armored soldiers pushing from the other side. You can’t let them in. They will eventually get in. It’s a high-pressure situation.

How long have you been pressed together? How long can you hold this formation? You can’t breathe. You are so hot from pressing against so many people for so long, and it’s the middle of summer. You run out to the balcony to catch your breath, just for a second. You pause to look at the horizon where the sun is just beginning to rise. Pastel pink fades to sherbet orange, yellow fades to light blue which fades into night sky. You feel trapped. You feel determined. You think about the power in this home at this moment: the power in throwing your body against the power of those who wish to deny the existence of your body. There is power in the sewer, and in the kiss between beloveds, and in the exchange of glances, you think to yourself. The sun rises a bit higher over the horizon; pink spreads a bit further across the sky. The smell of tear gas is less noticeable out here.

Dawn is about to break into morning, but what will happen to the house? You hear more coughing and yelling. You run back inside, join the bodies, press again.

To huddle

is to crowd together, nestle closely.

Heaped together

in a disorderly manner,

maybe some pressure.

A close grouping of people

or things.

Come closer.

Cue the chorus

line.

You are together

or

you are alone.

To mound

is to enclose or fortify or

heap into piles.

You are unevenly rounded.

A large pile or quantity of something.

Cue the chorus,

the noise and the bodies

in formation.

This article is part of the series by guest editor Christina Schmid