The Price of Admission

Suzanne Szucs interviews painter Adu Gindy about her show and that of Joy Kops and Peter Weizenegger. It is involved with life and death.

“Fables and Pyramids” explores the death of Adu Gindy’s longtime partner Kamal Gindy, and in a shocking twist marks the unexpected death of sculptor Peter Weizenegger.

When Adu Gindy talks about her work, the issue of “necessity” arises.

“My work isn’t really practical,” she says, her voice betraying remnants of a former life – a time when Adu felt she needed to justify herself as an artist. A child of World War II, leaving Estonia at age three – a homeland that she would never live in again – displaced in a refugee camp for 6 years and resettling in the Northeastern United States—with this in her past, it is easy to see how her mother, a tenacious arts and crafts teacher, would not wish for her daughter the impractical life of an artist. But practical and necessary are two different things. From my point of view, Adu Gindy’s artwork is indispensable. For her as well as for her audience, she demonstrates by her daily practice how fundamentally important it is to embrace and celebrate the mysteries of life, to confront our mortality with resilience, buoyancy and joy.

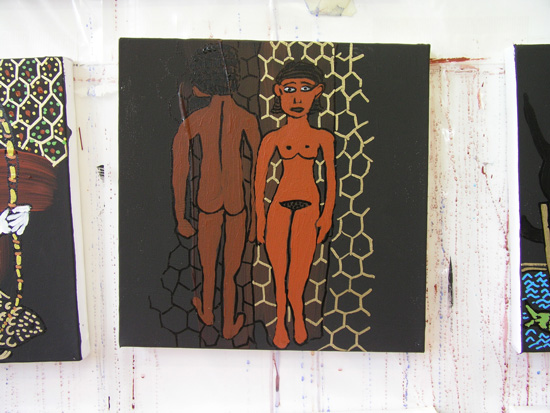

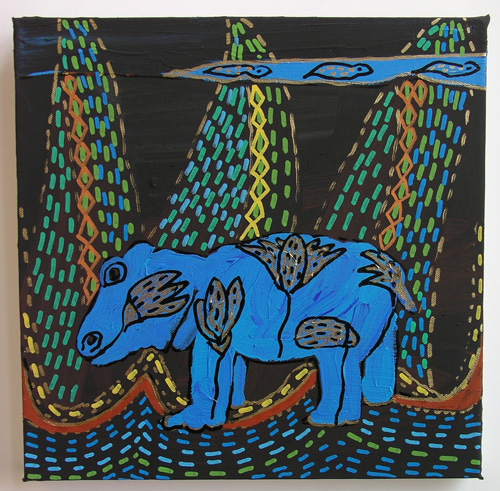

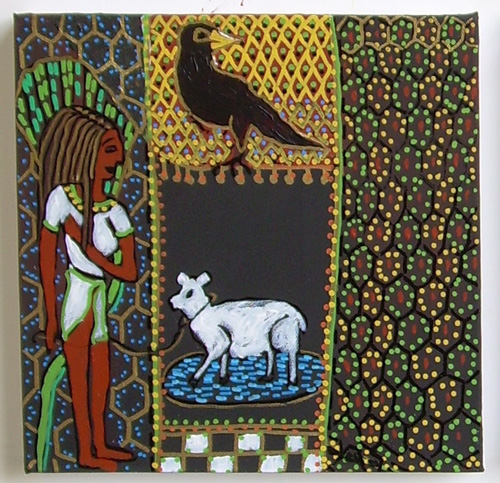

“Nothing gets destroyed, it just gets changed,” she remarks when talking about the recent death of her beloved husband, Kamal, for whom she has created her most recent project, Fables and Pyramids: Adu Gindy, Joy Kopps and Peter Weizenegger which will open at the Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth on May 29. For this project Gindy is creating a fanciful tomb in in the tradition of Kamal’s Egyptian heritage. It will also be marked by her signature of playful encounter with the world. Hundreds of 12”x12” paintings feature animals, bugs, gods and people all vying for attention in windows to some other existence to which Kamal, in his afterlife, or us in our imaginations, may travel. In this homage to Kamal she was to be accompanied by long-time friends Peter Weizenegger, who was creating a boat for the passing, and Joy Kops, who is making objects that celebrate the life that Adu and Kamal shared.

[Note: During the preparation for the show, in a terribly bitter turn, Peter Weizenegger was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer that took his life. The boat that he was to have built is being constructed to his design by Lyle Koivisto, Joy Kops’ husband. An account of Peter Weizenegger’s life will be published on mnartists next month]

Gindy’s journey is marked with twists and turns that surely inform her work, demonstrating a fierce and buoyant response to suffering. Homeless and living in a refuge camp with only her mother and grandmother (she would see her father again only twice in her life), she looks back on that time as forming her ability to turn the tables on trauma. “Part of that comes from my strongest childhood memories… being a kid you’d hear things… you got to know people… in the evenings there was no radio, no TV, you got together and told stories. I do remember a lot of laughter then. The war was over, yet we were in this no-man’s-land… when you are down to nothing, what do you do?” In Adu’s world, instead of giving in to the dark, you make light.

With the next bend in the path, Adu would grow up on a farm in Bethel, Connecticut, surrounded with the security missing from her early years. This time must have had a huge impact on Gindy, although she speaks of it sparingly, perhaps because it was relatively calm and free of the extreme trauma of her earlier years. The chickens and cows from farm life now dance through her paintings, happily thwarting hardship and suffering. Adu’s response to 9/11 was a series of paintings featuring bunnies and soccer balls as protagonists. They were the most resilient subjects she could think of, bouncing back from whatever might push them down.

From rural life to a scholarship to Vassar, Adu seemed to be following the path of so many other young women growing up in the ‘50s – a good, solid liberal arts education could be the ticket to a successful marriage and, indeed, Adu found herself living in New York City in a rent-controlled apartment with her new husband shortly after her graduation. Years after she had become accustomed to the abrasiveness of New Yorkers and learned to love the bubbling energy of the city, they relocated to Connecticut. Her husband would commute to his finance job and she would raise their children in the suburbs.

Life in Darien, Connecticut proved more illuminating than one might imagine after New York City. It was here that Adu really began exploring her artistic self, taking art classes from visiting Yale professors who would “slum” in the suburbs, teaching art to restless housewives. Eager to bring more art into their community, and hungry for it, Adu and her fellow students – wives and mothers – created opportunities to see and experience art locally. This was Adu’s entry point into community service, and falling in love with art was about finding herself. The 1980s were looming and feminism was making change possible for women. She had outgrown her marriage and made the difficult decision to leave it.

“It’s always been about truth to me. My work is what it is because it is my truth and it’s who I am, and yeah, I could do a bunch of other things, I suspect, but it’s not that inner truth that I feel is my voice, so I really tried to honor that.” As it called to her more and more, it became clear that a new path was emerging.

Unsure of herself as an artist, Adu left everything behind and embarked on a new life. She had found a soulmate in Kamal Gindy, who had taken a teaching position at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. She followed him on faith that this was the next, most truthful step on her path. This was a new kind of partnership – one in which Adu could be herself and “live the art on a daily basis.” After years of struggle, life fell into place and she and Kamal made the most of their new community, taking joy in exploring art and social activism. The two became pillars of the art community merely by supporting it. They never missed an opening and bought art from local artists until their house was full to bursting. His insistent curiosity fueled her own. Together they explored worlds that they may not have found without each other, and built a stronger, fuller community.

“How has Duluth formed you as an artist?” I asked, looking to connect her to the region.

“Well, it’s probably not the place, but the person I was with. Right now I can’t even recall thinking that I am not an artist. Sure, I know in my head, but it’s how I feel. It’s strange in a way that you bring it up. I’m smiling to myself because I can’t even think I was anything else… now, after Kamal is gone, I’m probably on my fourth life… I don’t know what it is going to be yet.”

The Egyptians once created elaborate tombs to send their loved ones into the afterlife with all the necessities they might need for a comfortable existence – whatever that may be. We study their handiwork now as if it was artistic expression, although I doubt they thought of it that way. It was crucial that loved ones have possessions both to support their afterlife and to provide testament to their status. Obviously the more stuff, the better. Murals in the tombs represented journeys that the dead would take; hopes for their new lives borne by their loved ones.

Studio practice is a constant for Adu; she’s there most days. With her thoughts consumed by Kamal and his illness, she found herself exploring Egyptian imagery as a salve. The resultant paintings, at first harboring loss and anguish, gravitated over time into portals – narrative possibilities for Kamal. Inadvertently, Adu began painting Kamal a tomb full of busy, colorful tableaus that appear to represent avenues to explore. She hopes to have at least 500 for the exhibition. It’s as though Adu can’t bear the thought of Kamal having any fewer opportunities for adventure than he had in life.

Looking at these images crowded together on the wall, or stacked in piles on her studio floor, I can’t help but to see them as windows. I feel that if I step into any one of them a whole narrative will begin that I might get lost in and then maybe, after time, I would step out of another. They seem to be moving, alive with a rich palette of clay red, gold and black. They seem to speak to one another, a rich river of consciousness.

“In my mind you can tell your own story, but I’ve altered them to a degree that you can walk into that story and whatever it is when you step into that world, it becomes yours really… it lives but it is ever-changing, so in that sense it’s really not a fixed permanence, rather an ongoing scenario.”

In January Adu met with Kamal’s family in Egypt and with them spread a portion of his ashes in the Red Sea. It was the day after his birthday. She saw that part of him, his physical existence, slide away into the water, forever in flux. Our lives are a construct of reality, shifting and changing. We turn right down our path on one day, left the next. In paying her respects to Kamal, Adu celebrates life. We can’t possibly know what death will be, but we can acknowledge it as a beautiful and inevitable stage in the journey. Being with the work, looking at it, soaking it in, it is easy to become entranced by this poetic vision, irrepressible and insistent, not very practical, but ever so necessary.

Fables and Pyramids: Adu Gindy, Joy Kopps and Peter Weizenegger will open at the Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth on May 29 and run through August 5.

This article originally appeared on mnartists.org on May 14, 2007.