The Mysterious Department of Public Design

Camille LeFevre investigates the so-called Department of Public Design and its cryptic "Interim Report on the Excavation of Zone 5," on view now at Form+Content Gallery. As details emerge she finds elements of the mystery are both solved and deepened.

So, what exactly is Zone 5? Those of us whose professional work and/or extracurricular proclivities lie at the intersections of art and architecture have been asking that very question, ever since something called The Department of Public Design (DoPD) began issuing missives on a project website and blog about its inaugural exhibition, Interim Report on the Excavation of Zone 5.

Back in May, the DoPD announced, via “Member Roehr” (that’s Michael Roehr, principal at RoehrSchmitt Architecture), that this so-called report is a project of a group of architects “interested in exploring new ways of working together that might leverage their particular (sometimes peculiar) skills and collective energy to new and unforeseen ends. The project itself is an effort to tease out that ever mystifying and primal relationship between things and meaning — how meaning imbues a thing; how a thing embodies meaning. This is a perennial question in our practice, and the question that holds the potential to open architecture well beyond itself.”

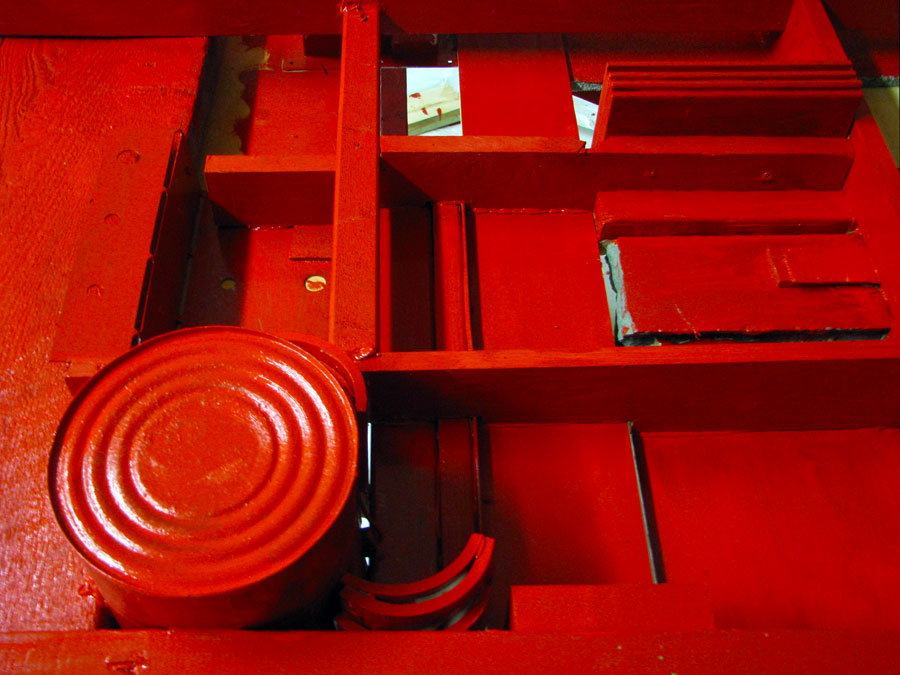

After that, things got far more cryptic in the DoPD’s communications. There were photos of “arcane assemblages” constructed of building materials and tools; pictures of supposedly “found” objects (a bird’s nest, planks with holes bored through them), artifacts (a computer keyboard, another nest, obscure objects), and “found” constructions (a composition of nail heads). There were mentions of a Council of Architects, purposefully and delightfully obfuscating memos, a picture of “the director” (a crow), announcements of hackings and “unauthorized” images and publicity, and images of red-saturated materials banged together.

On a recent Saturday evening, the shadow organization at last revealed itself at Form + Content Gallery in Minneapolis. So what exactly is Zone 5? Architects from five Twin Cities firms (Alchemy, ALTUS Architecture + Design, CityDeskStudio, Locus Architecture, and RoehrSchmitt/HLKB Architecture), in collaboration with curators Jay Isenberg (architect/artist) and Lynda Monick-Isenberg (artist/arts educator) having…well, having fun.

And if Roehr’s question on things and embodied meaning remains unanswered, so be it.

The “excavation” and “reassembly” are playful, investigative and well documented: Running along the gallery walls is a ribbon of photographs showing the participants in discussion, at work and in play. As observers, we’re simply along for the ride — or rather, we’re invited on walkabout into art history. Architect Garth Rockcastle‘s program note to the exhibition delves into architects’ perennial concerns with materials, waste, environmentalism and reuse, “detritus,” “collaboration,” “repurposing,” “ambiguity,” and the “monochromic” use of color — all of which have well-documented lineages in art history (which he traces, listing an artist for each code word above).

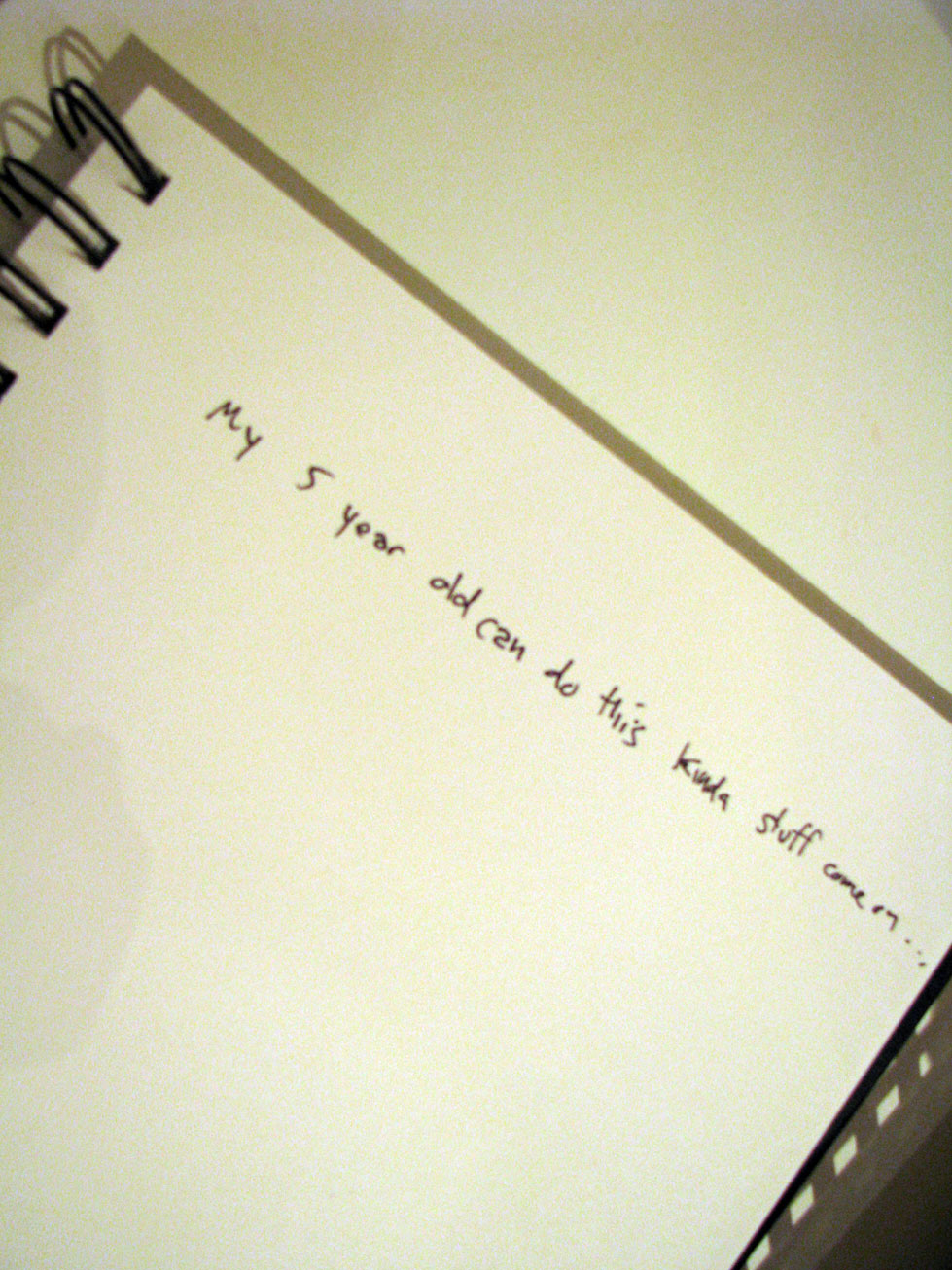

What is new in Zone 5, apparently, is summed up in this “unauthorized transmission” from the DoPD: “Rogue band of architects and troublemakers make things first and ask questions later in extended fit of parallel play.”

Cool.

The exhibition, or “catalogue,” is comprised of 12 “assemblages,” 10 “speculations,” and 15 “adorations.” Pieces hang from the ceiling like IKEA-gone-mad light fixtures, gatherings of metal or fabric material with objects strewn inside. They’re also installed on the walls as placards warning against crude and devilish intersections of flesh and metal (a fabric glove driven through with nails). Red hammers are strewn about the floor. Upended tree roots sit on top of metal poles, like piked heads wrenched from the earth. A child’s chair (constructed from a bent-plywood chair back, an inner tube and rope) is fastened to a plank bench — very Rauschenberg.

This is the stuff of our homes, our house projects, our gardens, our basements, our neighborhoods, reassembled to induce a sense of the uncanny and to declare, in a Duchampian sense, that art is what you decide it is.

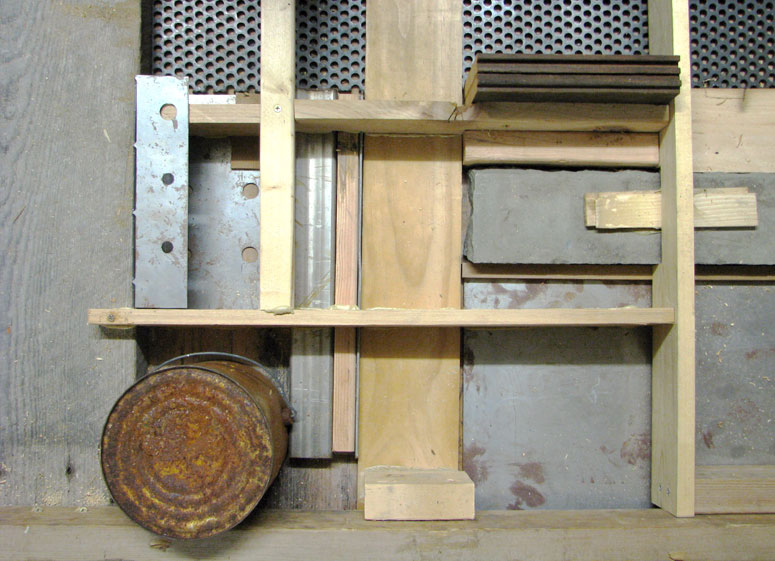

The acute materiality and quotidian nature of the works reflects the essence of what architects do: they make stuff. Hammers, nails, rope and wood; wire, metal mesh, rusted paint cans, cement board, paint brushes; windows and hinges; bird nest’s and tree roots; books and a knee-high plastic soldier. This is the stuff of our homes, our house projects, our gardens, our basements, our neighborhoods, reassembled to induce a sense of the uncanny and to declare, in a Duchampian sense, that art is what you decide it is.

Each of the works is numbered. None of them have provenance or authorship. In the middle of the gallery sits a large table to which everyone purportedly contributed. The table is a massive compilation of building materials, almost Nevelson-like, but unpainted — offering an archeological record of sorts, of group dynamics and creativity, or, like a George Morrison work, a record of a time and place.

About the enamel red: It’s luscious, alarming, and gruesome; it transforms a simple collage into a uniform cabinet of curiosities. The color also stands out in some of the photographs (see Monick-Isenberg’s shoes), which otherwise feature a lot of architects in black. As such, the color red is one of the group’s signatures, a warning to stop in your tracks and contemplate their decision to set aside the competitive nature of their personalities and their vocation, and to play together.

“What would happen if you gathered some of your most talented friends who were good at a lot of the same things that you were good at (and therefore competitors), and then tried to work with them on something that none of you might do alone?” asks one of DoPD’s “statements.” “This is not the way architects typically think.”

What occurred is this: “The group met for weeks in a vacant studio space, quickly dubbed ‘Zone 5,’ where they gathered while assembling the discarded and unused material and detritus of their profession,” according to another statement. “Talking loudly and simultaneously they began a furious process of ‘making’ that became the focus for their creative energy and passion for connecting, discussing, arguing and laughing.”

What resulted is an exhibition that both engages with art historical tradition and breaks with architectural stereotypes. What will they do next?

Related exhibition information: According to the blog for the Department of Public Design, “an ambiguous assortment of artifacts and materials recently uncovered in Zone 5 will be evaluated by the Council of Architects and presented in an exhibition of reassembly.” The show, curated by Jay H. Isenberg and Lynda Monick-Isenberg is on view at Form+Content Gallery in Minneapolis, through August 29.