The Experience of Time: Interview with Susan Kismaric

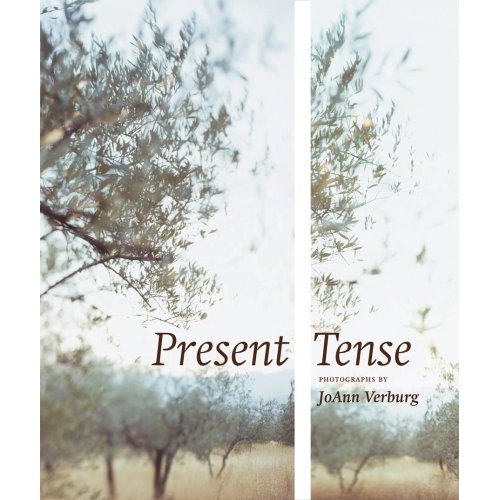

Mason Riddle interviewed Susan Kismaric, curator of "Present Tense: Photographs by JoAnn Verburg," opening January 12, 2008 at the Walker Art Center.

A handsome, articulate woman with graying hair, curator Susan Kismaric’s manner is relaxed and open. We spoke only one day after the Verberg show had opened at MoMA, on a very hot July afternoon. Her modest cubicle office, stacked with books and papers, has a window overlooking 53rd Street. During the interview, her fifteen-year-old daughter (who was leaving the next day for Norway) called with questions about how to do laundry and what to pack. At one point, Verburg, unexpectedly, stopped by the office to chat.

When did you first become interested in JoAnn Verburg’s photographs?

JoAnn first brought her work to show John in 1983. [John Szarkowski, Director Emeritus of the MoMa’s Department of Photography and a noted photographer in his own right, headed the museum’s photography department from 1962-1991. He died on July 7, 2007 at the age of 81.] We looked at her work – I think it was the first time JoAnn ever showed her work to a museum curator. We looked at some of her portraits – her series of heads. We bought the one of Mike Kelly and John Miller (With Michael and John in Minnesota, 1982) and the image of Sally Dixon and Ricardo (Sally and Ricardo, 1983).

She came back periodically over the years. Each time we bought a piece. John was very interested in her work. We hadn’t really seen work like she was making. In 1988 she came back and we bought a piece of Jim sleeping (Untitled (Jim Sleeping, Spoleto) 1988). [Poet Jim Moore is JoAnn’s husband] When she came back in 1993 she brought in her diptychs and triptychs. We bought 3 x Jim (1988), Still Life with Serial Killers (1991) and Secrets: Iraq (1991). By 1993 she had switched to color. And to photographing more of the domestic scenes. By the late 1990s she had started her olive trees series. We were lucky that in 2000 Clark Winter gave us Olive Trees After the Heat (1998), consisting of four images and, in 2002, Susan and Peter MacGill gave us Still Life with Jim (1991), a triptych.

From the beginning, what did you, or you and John find compelling about the work?

We immediately realized it was highly original, even though the work appears conventional on the surface, you know, portraits, still lifes, domestic scenes. In fact, they were highly unconventional. Also, the work was technically superb. We realized these were highly seductive images.

Can you describe exactly what you find so seductive? You and John obviously looked at many images.

It is this connection between the people, the subjects, and the images themselves. The images reveal how we define ourselves. Formally, they are very interesting photographs. But they are also very experiential. We had not quite seen anything like it. There is this idea of time in her work. What you are looking at is “in between” what has just happened and what will happen next. At the time, John Coplans was the only other photographer working in series like this. And there are similarities to Josef Albers’ collaged portraits done at the Bauhaus in the 1920s and 1930s. But, JoAnn’s are unique. There is this unique element of time in all of her photographs.

With JoAnn’s work, the viewer has this sense that something is about to, or has just happened. There is a sense of going forward or backward in time. It was very imaginative. And JoAnn has continued to do this. John recognized this immediately.

Do you think the viewer understands this?

JoAnn’s photographs give the viewer the option to enter the picture or not. These are not aggressive images. They invite you in without being aggressive. Whether the viewer is going to do this – to actually take the time to enter and think about the image – is another question. So much contemporary art – well, it either leads the viewer by the nose, or people are absolutely mystified by it. This is not JoAnn. JoAnn’s work allows the viewer to enter, if they are open to it.

Do you find other aspects of JoAnn’s work unique, besides the time element?

In the 1980s few photographers were working in series. Maybe Robert Adams. JoAnn’s work requires a concentration to understand it. She has given up an intellectual apparatus for an experiential one. There is also this impressive formal and technical technique. The work is not intellectual in a theoretical sense. It is very emotional work. If you are open to it, you get it. But they aren’t just pretty pictures. Her work operates on many levels.

What would allow someone enter the work or not?

JoAnn’s work raises a lot of questions. It is very accessible; it appears so recognizable at first, that you could pass it by. But you have to give yourself up to it. It is not aggressive. It doesn’t tell you how to feel. Serra, my god, is brilliant. But there can be a lot of anxiety for the viewer with Serra. It can be overwhelming. [The exhibition Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years is on view at MoMA through September 10, 2007.]

I like not always being overwhelmed. JoAnn’s work doesn’t overwhelm you. Her work is emotional if you take the time, but it is not overwhelming. It is not assertive. It is a slow experience. It is good not always to be overwhelmed.

Can you explain this idea of “experience” in JoAnn’s work – how you think of this “experience”?

It is a lot about JoAnn. It is about how she thinks about photography – the photograph. It is about her experience taking photographs. It is a very subtle quality. After RIT her knowledge of the technology of photography was very, very thorough. [Verburg received her master’s degree in photography in 1976 from the Rochester Institute of Technology]. As we go along in the development of photography, this kind of knowledge grows less and less important. Digital photography has taken care of much of that. An intern the other day asked me about JoAnn’s images of trees, the olive trees, assuming they were digital and this was how she got the quality that she did. When I said “ No. She uses a 5 x 7 camera,” he was stupefied.

There really is such a difference between film and digital, JoAnn’s work reminds us of that.

Yes. There really is such a difference. Film is just so much more visceral. You can just tell it.

With regard to this notion of “time” in JoAnn’s work, this sense that pervades her work, do you think it is different in the black-and-white images versus the color images?

I don’t know. I don’t know if there is a difference. No one has really discussed this difference between black-and-white and color. Color may make the image less abstract – we do live in a color world. JoAnn says color gives her images more dimensionality. I don’t know that I agree. I might think that it is the opposite. The light in her black-and-white images – that quality of light – it gives these images a much more sculptural quality.

Are there other photographers, contemporary photographers, who approach concepts of time in their work like JoAnn?

In JoAnn’s work there is this notion of the expansion of time. Her images describe a tension in time. Few photographers have done this. I think JoAnn’s work shows this possibility, this possibility of deciphering time. Maybe Philip-Lorca diCorcia. But he has taken it to the extreme, to the point that his images are very dramatic and cinematic. The light is all artificial.

Was organizing a one-person show of JoAnn’s work a risk, as it is not widely known?

No. It was not a risk. In fact, just the opposite. John [Szarkowski] and I had always admired her work – we had been buying it for the collection for more than twenty years. We are talking about a photographer with more than thirty years of experience. I felt it was time to do the work justice. There was no book. There was no major show. Yet, her work is unique. It was important to flesh the work out. To give it justification. No, this was not a risk. I was keenly interested in the work. I have been at MoMA for more than one-half of my life. I try to, as I think do all of the curators, here, organize shows of work I am interested in – work I believe in.

Once, many years ago, I was curating a show from our collection of images of children. Then I learned a very important gallery was doing a show of photographs of children. I questioned what I was doing. I was thinking of not moving forward with it. I talked to John about it. He said, “You can’t do a show if you think someone is looking over your shoulder. You need to do what you believe in.” I believe in JoAnn’s work. It is exciting. It is not well known. It is a woman over fifty who is doing unique work which has not been widely seen.

The qualities of her work are very different than the qualities in other contemporary photography. Her work is so experiential. This is missing from so much contemporary photography. No, organizing this exhibition was not a risk. Not at all.

Ms. Kismaric has been at MoMA since 1976 and has been a curator in the Department of Photography since 1986. She has organized numerous exhibitions, including Fashioning Fiction in Photography (2004), David Goldblatt: Photographs from South Africa (1998), Manual Alvarez Bravo (1997) and Self-Portrait: The Photograph’s Persona 1840-1985 (1985) among many other shows. She has authored numerous books and has been a visiting Senior Critic of Photography at the Yale School of Art since the early 1980s.

Present Tense will travel to the Walker Art Center where it will be on view from January 13 through April 20, 2008.

In the spirit of full disclosure, Mason Riddle met JoAnn Verburg in 1982/83 when she was waitressing at Monte Carlo restaurant and Verburg was a visiting artist at MCAD. They have been friends and colleagues since. She first wrote about Verburg’s work in 1986. In 2002, as director of the Minnesota Percent for Art in Public Places program, Riddle’s Mill City Museum artist selection committee commissioned Verburg to create a major photographic work on glass, which can be seen on the main floor of the museum.