The Escape Artist

Consider Samantha French's bright, Impressionistic paintings of a summer idyll: When so much contemporary art seeks to shock and surprise, to push boundaries, is such an unabashedly pleasant, familiar style of work still relevant to the conversation?

Last summer I when to Soo Visual Arts Center to see a show by Samantha French, a Minnesota painter living in New York. The paintings were bright and lively, mostly of young people underwater in swimming pools, happy, enjoying themselves. I immediately fell in love with the work but just as immediately wondered if it was really all right to enjoy such openly, exuberantly pleasant paintings. I was disarmed by the idea that her modern day Impressionist works were acting on me just as Monet said he wanted his works to, as a “balm for the modern soul.”

The work, and my quandary over it, stuck with me. And this summer I had the opportunity to visit Samantha French in her Bushwick studio. In case you don’t know, Bushwick is sort of the last bastion of inexpensive apartments and artist spaces in Brooklyn, although the neighborhood is currently undergoing rapid gentrification that is bringing with it skyrocketing rents. Still, one can wander the streets and get a sense for the way it was not so long ago. With its broken windows, heavily tagged warehouses and litter-crowded sidewalks, even now it’s a gritty, cinematic urban landscape that offers a striking contrast to French’s work — and perhaps some understanding into its raison d’être.

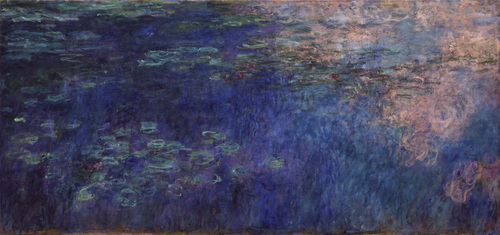

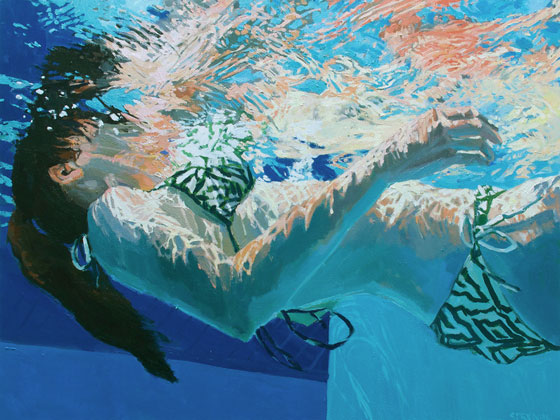

The paintings are figurative, the swimmers recognizable and, when reduced from their larger size to a snapshot on a computer screen, the images look highly realistic. But in person, at full scale on the wall, you can see the loose brushwork, the bold strokes and, around the edges where the water ripples and the light bends, a magical chaos surrounds those apparently tidy forms. These busy sections of abstraction are what originally drew me into the paintings and then kept me there, augmenting that initial attraction by rewarding prolonged study. The swimmers are moving through a distinctly Ab-Ex background – sufficiently recognizable as such that one gets the sense French’s paintings might offer a kind of visual history of 20th Century art, writ small. Of course, Impressionist works came first, foreshadowing Abstract Expressionism: look, and you see Monet’s water lilies often wander away from distinct forms into non-figurative, colorful chaos. And with French’s work, I similarly find myself studying the swirls and eddies, getting dreamily lost in the rippled green of the trees alongside the swimming pool. The art is doing its job.

Visual art is at an interesting historical moment. As Arthur Danto writes in his new book, What Art Is, “today art can be made of anything, put together with anything, in the service of presenting any ideas whatsoever.” When you consider French’s work and that of others like her, a particularly compelling question arises: In a time when much of contemporary art seeks to shock and surprise, both with its materials and its subject matter — always pushing forward to expand the boundaries of that elusive thing called “art” — what do we do when an artist chooses to work in a familiar mode, one we recognize and maybe even feel we already understand? I recently talked to someone in a graduate visual arts program; he said one of his fellow students paints very much like Rembrandt, or at least in the style of the 17th-century Dutch school. When it came time to critique his work, apparently, everyone was flummoxed, all his teachers and fellow students unsure what to say. One question they were no doubt thinking, if not speaking aloud: Can you still paint like that? Can such art really be relevant today?

Samantha French’s paintings have all the hallmarks of French Impressionism–the play of light, her use of water, the pleasure she unabashedly depicts and invokes. But the artist says she tries to keep art history out of her mind when she paints. While she is, of course, aware of the Impressionists, she says, she never sets out to try and emulate them. She’s not attempting to channel some turn-of-the-19th-century plein air painter capturing the French seaside. In fact, she tries to not let that past, or any other, invade her creative process at all, she insists. She says she’s focused on her own creative history, her own vision.

The moment is one of summer when you’re fifteen, filled with an offhand exuberance, a sense of possibility. It’s a moment that is quickly gone. French’s paintings let us linger over that fleeing moment, grabbing onto the light that dapples the bodies of swimmers and the swirling waters around them.

French grew up in the Brainerd Lakes area, surrounded by northwoods beaches that remained frozen much of the year. But when summer came and the waters thawed, they offered a playful escape to everyone who lived there (as well as many of us who didn’t). That moment, when spring becomes summer, and its impact on her youthful consciousness is what French is referencing in her work. It’s the escape from a harsh winter into a welcoming environment. She says she has always been drawn to the water that surrounded her growing-up years, that she spent countless summer days at the beach, many of her first paintings featured boats on local lakes, and the time spent there indelibly marked her imagination. Those years of growing up have been distilled into one image, someone underwater, swimming in a pool, and it has become the focus of her painting.

For the swimming pool paintings, French works from photographs. The impact of photography on her work is an interesting digression that I’ll only touch on here, but it’s noteworthy that she spends nearly as many hours taking underwater photographs as she does painting. Photographs freeze time in a way the human eye cannot: one can stop the rippling water, revealing a world we can never actually see, never hold on to, in the moment.

French takes photos numbering in the thousands in pursuit of an elusive goal: the image that captures what she calls a “specific moment of emotional time.” The moment, she says, is one of summer when you’re fifteen, filled with an offhand exuberance, a sense of possibility; it’s a moment that is fleeting and quickly gone, an experience much like going underwater, enjoying a cool respite from the hot, humid Minnesota air, but knowing you’ll have to go back up soon. It’s the sense you have, even in summer, that winter is just around the corner; or maybe, that the streets of Bushwick are outside. (I love the streets of Bushwick, as does French, and there is some incredible graffiti art in the neighborhood, but those streets stand in marked counterpoint to her summer idyll, nonetheless.) French’s most effective paintings let us linger over that fleeing moment, grabbing onto the light that dapples the bodies of swimmers and the swirling waters around them. In her images, we can sense the continuous movement before and after, we know what happens next but we want to stay with this as long as we can, like a kid who doesn’t want to get out of the pool.

And surrounding the swimmers are those bright fields of chaos; it’s her abstract world on the periphery that I get lost in. French says that she gets lost in these eddies of mark-making, too, where what is being represented is the distortion rather than the thing itself, the effects of water disturbed by the swimmer’s arms and hands. She says there is more freedom for her here in the margins, where she can focus on each individual mark she makes. Each brush stroke of color exists only for itself, outside the flow of time. She says these abstracted sections offer escape from overtly conscious intention and that they are the part of the painting she spends most of her time on. It’s time well spent because these obsessively worked sections are the secret to the impact of her work. Those swirling constellations of light and impossible paisleys of green trees and blue sky, the bubbles exhaled by the swimmers coming up for air, caught in the moment of making the very alternate universe into which they have escaped for a few seconds – these elements are crucial. In these celestial backgrounds, her swimmers become something more — secular icons of something elemental, the very picture of human joy.

And here again, we return to the Impressionists, to Monet’s “balm for the modern soul.” In a way, it’s as if French has independently come to the same place, albeit via much different geography and a hundred years later.

As much as French’s work offers sanctuary from the day-to-day grind of modern life, the paintings are an escape from much of contemporary art, too — a refuge from its oblique challenge and difficulty. We are at a moment in art history (perhaps already through it) that tends toward explorations of unaesthetic art — ugly art, if you will. This inclination, this way of seeing has been so dominant, in fact, that I questioned myself when I first saw French’s work. I wondered if such lovely paintings could have real emotional depth and meaning.

I am still fascinated by that first question: Can we paint like this now? But maybe a better one is: Why wouldn’t we? We play the piano in a variety of ways, why not paint according to a similarly generous palette? Perhaps a part of this historical moment in painting is a growing acceptance of these past modes as still-viable means of expression, the conviction that art-making doesn’t need to pursue endless novelty to create work that offers surprise and delight. It’s all just paint on canvas. Sometimes “the new” is just an illusion, anyway, a trick we play on ourselves.

The intention behind French’s works may be clear, the mode of their creation more familiar, but that doesn’t explain away or discount the complex human emotion, the mystery contained in them. There is no dogma here, no particular reading required — just an image, real emotion made manifest.