The Digital World Has Made Performers of Us All

The best writing online does more than put beautifully turned phrases on a screen — it performs ideas in digital space. It takes advantage of the distinct contours of the web, making use of the full range of tools at hand in this new medium.

I won’t blow your mind, I assume, if I say that writing for a digital space isn’t the same as writing for print. We are discussing issues around digital constantly —Superscript, right? — trying to figure out just what the hell we’re all doing online, and how we might continue to create substantive work on a platform where the thing that makes money and gets discussed is a listicle of our favorite celebrity butt moles.1

Central to those concerns are the questions: What exactly is this digital space? How is it different, how is it significant, and, specifically, how is this medium new, exciting, and important for the craft of writing? I think the answer to many of these questions is this: Writing for the web is a performance. Sure, I want to read the New York Times online, and I’m fine with the fact that it’s basically the same thing I’d get in print. 2 But the best writing in digital spaces, the writing that sticks in your mind like a blow dart, offers something more — it performs.

The digital world has made performers of us all. And writing online that doesn’t perform is just writing for print that happens to be manifest in the form of pixels. When a writer is performing ideas in a digital space, they have a toolbox that includes most of the tools available when writing for print in addition to those that take advantage of what’s possible online. Largely, writing for the web entails not a removal of assets, but an increase in the possibilities for the performance. For instance, in digital spaces the writer can link to other places on the internet, sending the reader on a scavenger hunt or pushing them down a worm hole in time. Even within the act of linking, the writer must decide: should the linked page supplant the page the reader is on? Or, should that clicked link open into a new tab, telling the reader, Hey, stay with me now, but later, you should totally check this out. You’re going to love it. If you’re using the digital space to its full capacity, that’s a decision you, the writer, should make.

The writer can add music. Or a video. Or a GIF. They can find ways to play with the manner in which the reader receives the information: Should your piece have its own site; does it need a reliable name in the header like “Mn Artists,” or does it belong on a personal blog? Or, is it an immersive experience? Something that requires a little more work to dig into? Maybe you construct it for Apple Watch, or build a text for anachronistic technology such that it must be heard on a Zune.

And that’s just scratching the surface.3

I can argue forever about why digital writing is a performance, but the important part is, as a writer, realizing that it is a performance. And to perform well, we need to understand what kind of tools are at hand. Thinking this way opens up the range of possibilities available online that allow a piece of writing to achieve its goals more effectively, revealing more innovative paths to the desired end. I’m going to touch on a few of these possibilities, but my list is by no means exhaustive, nor is the manner in which digital work may exist static. It’s growing and evolving daily.

Performing, Literally

One way of doing this is actually to perform the writing. Think of podcasts. No one would argue that a show like Serial would be more compelling as a blog post. And it’s not just journalism that stands to benefit. Podcasts like We’re Alive or The Leviathan Chronicles rethink fiction as a performance, turning written narratives into multimedia experiences, complete with actors, sound effects, and scores. The two shows I’ve written for in this vein — The Locals and Radio Happy Hour — took the performance aspects of such writing even further. The shows are both narratives intended for podcast, but they are recorded in front of a live (drunk) audience and so retain that in-the-moment flavor. From the sound of a squeaky door to spontaneous, drunken laughter, its inclusion in the show is a decision the writer is making in aid of a performance. Twenty years ago, if you wrote a comedy script, you sent it off to a producer, an agent, an editor. Now, in most instances, writers build a show like these from scratch— from writing, editing and posting the finished podcast to finding the actors and musicians whose contributions enrich it. Every piece of this process can be within the writer’s control and is, in turn, a part of the craft, a part of the writing.

Even more blog-like writing can successfully take this form, when the writing demands it or can benefit from it. Take Cory McAbee’s Smallest Star podcast. Particularly, the early episodes took the form of a rambling blog post, diatribes on everything and nothing that hinged on the enactment of the writing to create a sort of performance art morning zoo.

I played with this form of writing as performance, myself, stepping away from podcasts, in a piece of video intended for digital distribution called STRIKE TWO.

I first wrote a literal, words-only translation of Sergei Eisenstein’s silent film Strike (1925), but decided to perform it in front of a camera, after the fashion of a vlog, rather than treating it as a static publication. Moving still further into performance, the sequel will soon be performed live in a gallery and streamed online, with a live score from Morricone Youth.

That leads us to still another way that artists and writers make the digital space compelling through performance — events. Transatlantic Poetry does a great job of this. They put together live readings with poets on opposite sides of the globe. Sure, the event is archived, and you can watch it on YouTube later, but the real-time conceit is compelling. I want to “be there” while these are read. I want to see it happen. I want to see it performed.

This is something we played with at InDigest, too, when we put together an event in 2012 for the Mayan Apocalypse called “The Last Reading on Earth, Ever,”. We invited writers to bring apocalyptic poems and stories into video form. None of it was live, but it was time-sensitive, intended as a marathon reading for the day of an apocalypse that never came. Some writers read their work into the camera, some made art video versions of their writing, and then some, like Joseph Bates, channeled Orson Welles and brought a whole new angle to the prompt, creating something that might not have a home anywhere else but in a digital space like this.

Playing in Time

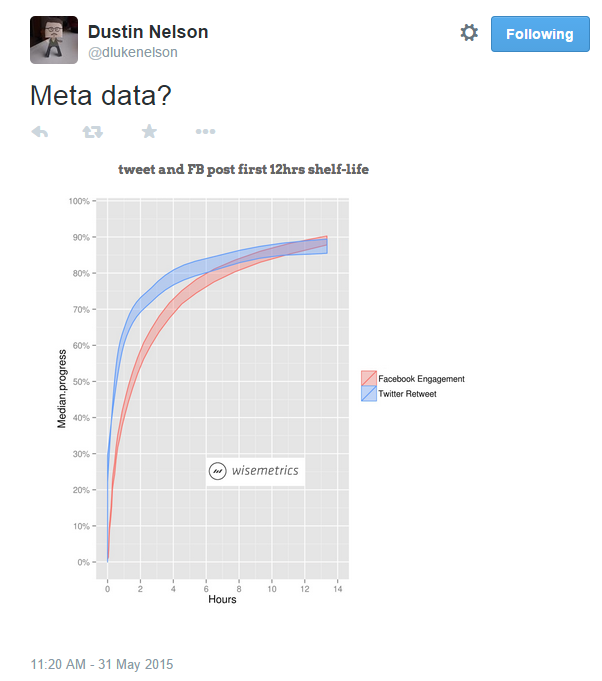

Moving forward from digital “events,” let’s think of time more broadly, as material. Time is essential to performance. It’s central. Yet, there’s a funny relationship between time and the internet. At first glance, writers were thrilled about the internet, because work lives forever. Then, as the internet was flooded with writing and information, we realized that the writing might “live forever” in the sense that it can be found, but whether or not it actually will be is a different story entirely. It’s tough to make something stick online when 300 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute. Some research suggests half of a tweet’s engagements happen in the first 24 minutes. For a Facebook post, it’s an hour. Blog posts tend to not be seen again after 27 days.

In that sense, “forever” is kind of temporary. Realizing that, we went to war. Writers are now required to know how to battle the natural tendency of “content” to disappear. They have to know about keywords and SEO. Make it shareable. Share it yourself. Write evergreen content. And so on.

So, how about this? I say, don’t fight it. Embrace the tendency of digital content to disappear. Indeed, force the writing disappear. It’s a project I’ve tried: Publishing a poem and then removing one word every day until the poem disappears. It’s a living thing. Why not intentionally let your writing recede from view the way it’s going to anyway? Play with its ephemerality. One brilliant example is the Finnish video artist and poet J.P. Sipila’s “Sleight of Tree.” It was a web installation the writer would update from time to time — new parts would enter, some pieces would move, others would vanish entirely. The process of the poem’s shifting was laid bare, but also provided a sense of urgency in the viewer, a desire to process its evolutions.

Video, At Large

This won’t blow your mind either: Make a video. Most writers don’t give video much consideration, thinking that they can’t learn the tools or that it’s excessively complicated. But producing moving images is not only possible, it’s never been easier. That phone in your pocket, or the device you’re reading this on? You can construct an entire video on there. Or you could head over to an incredible resource like archive.org (thank you, Rick Prelinger) and build something out of archival footage. You’ve written a poem? Make it a videopoem. Or remix something if you don’t have a poem — remixing! yet another possibility — and build a videopoem out of someone else’s work. The Poetry Storehouse is full of poems being shared through Creative Commons for just such collaborative projects. Working on an essay? Does it really work best as a traditional piece of writing, or is there something to be gained by putting it in video form? Look at the work of John Bresland, take “Mangoes” for example, which was shot and edited on an iPhone. The emotional weight of a videoessay like this is another great example of what’s possible when the writing is performed. Bresland’s text here isn’t meant to sit on the page. It wouldn’t work as well.

I’m Not Going to Get Through All This

The possibilities are endless. Look at the comics of Stephen Halker – like ”The Check Heard ‘Round the World” – and see a great comic book artist doing something online that would be simply impossible in a static medium.

You could:

Use Periscope to write a live video essay.

Write code that lives as a poem, but has a second life when implemented.

Turn poems into GIFs.

Writing a memoir in GIFs or building an immersive environment for a short story is no substitute for writing well, but writing well in collusion with intelligent use of the vast performative possibilities of the digital landscape brings text-based work to a new level. Think of a film. A good script is something special. A good script in the hands of a good director, with a good cinematographer, with a cast that understands the roles, is something extraordinary. The writer in digital space just has to perform every job on this set. It’s a daunting task, maybe, but also thrilling and alive with possibility.

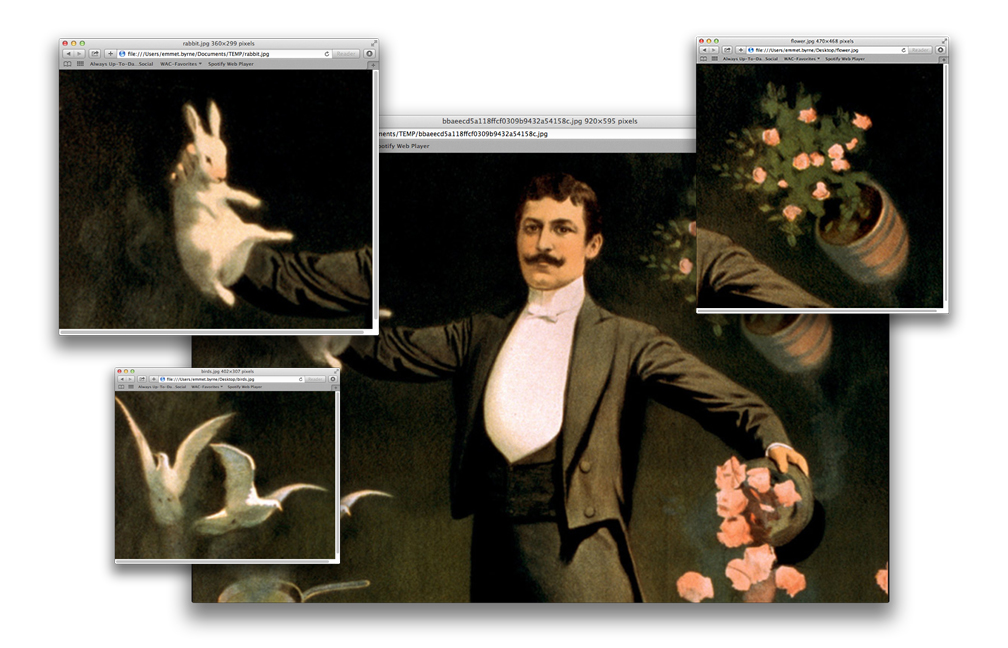

The internet is fucking magic. Act accordingly.