Seeing Target Field

Michael Fallon offers a fan's eye view on artistic and architectural character of Target Field with a wholly subjective, sprawling, and entirely engaging assessment of the aesthetic, cultural, political and philosophical merits of the Twins' new ballpark

Making an informed assessment of Target Field is a daunting undertaking. And it’s not just because of the local hoopla surrounding the ballpark’s opening, during which it suddenly seemed, around April 1 or so, that every eye in the state of Minnesota was fixed on the place. Nor is it because of the weight of the outpouring of praise for the stadium that has been offered up by all manner of local and national observers over the past several months. No, the problem with assessing Target Field is that there are just too many ways to look at a ballpark, too many points of reference. To examine fully the sociological, economic, political, historical, practical/technical, athletic, artistic, architectural, even epistemological aspects of Target Field would require (approximately) 27 separate reviews, and this, of course, is the last thing anyone has time and space for.

What follows, then, is a somewhat incomplete and wholly subjective mass of observations about Target Field, made during its first month or so of operation over the course of four complete home ball games — three in April, one in May; three during the day, one in the evening; two with a four-month-old child in tow, two without; three victories and one defeat — as well as during one private backstage tour given to the writer by two gracious, charming, and knowledgeable young Twins’ staffers. If I’ve left anything out, I take complete responsibility for its lack.

I. Some Observations on How Target Field Is Experienced by Fans, and How the Place Functions as a Structure for the Playing and Viewing of Baseball Games

The first observation one is likely to make about Target Field is how intimate the place feels. Compared to most other major league baseball stadiums, Target Field is a cigar box. It is built on one of the smallest plots in the Major Leagues, an 8.5-acre footprint that is at the small end for ballparks — about the same size as Boston’s Fenway Park. Though unlike Fenway Park, Target Field’s structure is cantilevered up from its base plot, built up with pilings and modern ingenuity so that it mushrooms out over its surroundings, giving the structure more like 12 acres of room, or about 1,000,000 square feet. In comparison, the Metrodome — built at the apogee of the suburban-oriented, multi-purpose, massive stadium building trend — has a square footage of 1,200,000, while the new Yankee Stadium, opened the year before Target Field, is comprised of almost 1,300,000 square feet (but more about that in a bit).

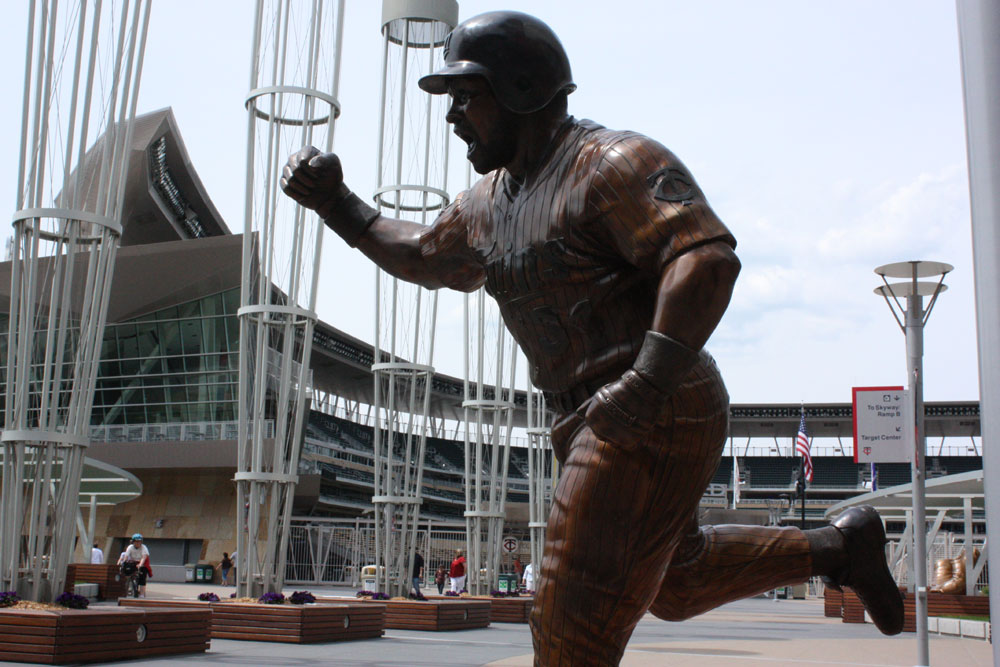

The sense of intimacy at Target Field isn’t merely a matter of the stadium’s modest size and tight layout. The stadium seems designed, first and foremost, with the human scale in mind. For instance, the main entrance — where the majority of fans will enter the game — Target Plaza, is akin to the front porch of a large Victorian house on a bustling city avenue: open and homey, flanked by other buildings, and comfortably filled with people. Target Plaza is the perfect place to meet someone for a game. “Meet me by the statue of Kirby Puckett in Target Plaza,” you might say to your friend. “You know the one of him circling the bases after his game-winning dinger in Game 6 of the 1991 World Series.” (Bronze statues of Puckett, Harmon Killebrew, and Rod Carew, each created by local artist Bill Mack, are sited just outside the stadium.)

Once met, your cohort and you enter through comfortably wide ticket gates and move into the great, open living space of the stadium, where people meander at ease, taking in the sights before settling into their seats for the game. Moving through Target Field, in fact, is akin to moving through a neighborhood — a quirky neighborhood, with any number of unusual points of interest. Since its plot is an odd and unevenly shaped segment carved out of the downtown, designers could easily have been bogged down in logistical problems. Instead, the design of Target Field turns a potential weakness into a strength, incorporating its odd spaces into the whole experience. For instance, an observation area beyond Target Plaza spills over the field behind the right field bleachers, hanging precariously over the field (!). Through all the games I attended, a haphazard tangle of fans stood behind this area, mingling, talking, sometimes even taking in the game — all the while, thoroughly enjoying themselves. Move down the first-base foul line a ways, and you find another open gathering area on the main concourse. In another part of the outfield, underneath the massive neon-lit replica of an old Twins logo, another observation area sits above the fence in dead center field. Further along, in the far left-field corner, a special Budweiser Roof Deck has views of the city on one side, the game on the other, and a fire pit smack in the middle. And directly underneath this area is the Captain Morgan bar area and observation deck, a place, I came to find out, that is optimal for an ad-hoc meat-market of the young and good-looking.

There are still more gathering spaces throughout the park — a new feature, and moneymaking enterprise for the team, that is much different from what was offered at the Metrodome. These include bars/grills named for Harmon Killebrew and Kent Hrbek, a tavern that gives tribute to local “town ball,” and several private clubs — the Metropolitan Club, the Legends Club, and the Champions club, each one more exclusive and lavish than the last. What connects all of these gathering spots, both private and public, are the wide, bustling concourses. The flow of people on these thoroughfares is almost constant, but it is hardly ever uncomfortable. This is a fun, walkable village, where you find a series of interesting gathering spots throughout as you wander through. It’s a place you feel compelled to revisit again and again. Though, to be fair, it may also be an annoyance to the baseball purist who finds the coming and going of the crowds a distraction to the raison d’etre — i.e., a game of good baseball.

As for the game experience at Target Field, if you spend any time at all in the stadium you will inevitably hear someone say these words: “Wow, there’s not a bad seat in the house.” Everything seems unrealistically close by. One reason for this is the stadium’s single design focus: for baseball games. This seems overly simplistic, but the fact is that the games we like to watch in America, in particular baseball and football, have vastly different viewing requirements. The field in baseball is an odd shape, with the origination point at the center of a diamond, and then a circular arc in the outfield on two sides of the diamond (but not on the other two). This off-kilter design requires seating that is angled toward the fixed point of the stretch between the pitcher’s mound and home plate, where all action on the field starts before it sprays out to all corners of the diamond and outfield arc. This is much different than the back-forth linear action of the football gridiron, something that designers of the Metrodome — and of the many single-purpose stadiums built between the mid-60s and mid-80s — seemed unconcerned about. Because Target Field is designed for baseball viewing only, fans no longer need to crane their necks or lean forward in their seats to watch the action.

The Metropolitan Club juts out like a glacial Fortress of Solitude, all cool blue glass and angular steel. The great canopy that is perched atop the roofless upper grandstands rises up from the structure like a Cylon Basestar. Meanwhile, the Kasota stone masonry that clads the structure lends a kind of homey, Planet Minnesota warmth.

Another reason that most seats are good at Target Field is thanks to its contemporary design, both in terms of building technique and seating layout. Modern stadium building techniques avoid the need for obstructing columns, beams, and joists, meaning that the 1,400 obstructed-view seats at the Metrodome have been reduced to (officially) fewer than 200 such seats at the Twins’ new home. Target Field’s seats, as a rule, also seem closer to the field. And from the outfield bleachers, where I’ve been sitting, stadium seats on the other side of the field (behind home plate) appear oddly close, as if just beyond the reach of my outstretched arm. This feeling, akin to an optical illusion, is the result of a key feature of modern stadium design, as practiced by specialized firms like Populous, who designed Target Field (along with new stadiums in San Francisco, Baltimore, and Pittsburgh). The seating structures in new stadiums today are built on a sort of catenary curve. Meaning, the rise of the stands at the bottom is very flat, curving upward very gradually until a certain optimal point is reached. From there, the stands suddenly curve upward ever more sharply. This yields several results. First, there are more lower seats in such stadiums than upper seats. In Target Field, 20,000 of its seats are in the lower deck, while 13,468 are in the upper (compared to 21,621 lower deck seats at the Metrodome, and 28,779 upper deck seats). And second, the higher-up seats, thanks to that sharp upward curve, are closer to the field than they otherwise would be.

Game experience aside, everyone will find something to enjoy about the stadium. Along with its quirky, neighborhoody feel, Target Field’s architecture, on the whole, is delightfully modern and occasionally surprising. In some places, Target Field resembles a giant space dock. Just off Target Plaza, for example, the Metropolitan Club juts out into its surroundings like a glacial Fortress of Solitude, all cool blue glass and angular steel. And the stadium’s single most distinctive architectural feature, the great canopy that is perched atop the roofless upper grandstands, rises up from the structure like a Cylon Basestar. Meanwhile, the Kasota stone masonry that clads the structure lends a kind of homey, Planet Minnesota warmth. Much of the stone is roughhewn, raw and textural, and variegated in color throughout — bringing to mind the great fin de siecle robber-baron mansions on Pillsbury Ave in Minneapolis and Summit Avenue in St. Paul. Inside the ballpark, from the vantage point of the stands, while viewing the game, the stone is still present, but it fades into the background. If I have any personal criticism of the architecture, and the experience of the stadium, it’s that the grandstand levels inside the park seem relatively unfinished. This is a small quibble, but most of what is visible of the structure from inside the park is the raw compressed concrete of the stands, the steel in railings and window frames, and the glass of private clubs. The dull grayness of these dominant features ends up overshadowing the warmth and beauty that is otherwise present throughout the stadium.

II. Some Observations on How Target Field Fits into Its Downtown Surroundings

Target Field is nestled tightly into a tangle of modern freeway tunnels, roadways, parking structures, and the old warehouses and other buildings in the North Loop/Warehouse District neighborhood. In a sense, the stadium seems to resemble a keystone, capping the downtown areas to the east of the Field, and providing a transition point to what lies to the west (a rolling swath of roads, warehouses, and light industrial buildings that used to be prairie). Because of how tightly the stadium fits into its location, Target Field’s confines are broken by several nearby buildings, and from certain spots in the outfield you can actually reach out and touch them. Meanwhile, behind the outfield, the downtown skyline is dauntingly visible, standing at attention like a battalion of Japanese movie monsters. It will take some time before it feels like Target Field was always meant to be in this spot.

From the looks of things during the first month of the season, however, locals have taken the new stadium in stride. Game time is now a flurry of activity and bustling crowds, making the Warehouse District feel like a pedestrian mall in a busy European capitol city. Considering the conflicting data about the economic effect that stadiums are said to have on their neighborhoods, it’s difficult to tell what the North Loop/Warehouse District will become in the long run, and how Target Field will influence its neighborhood. Development plans that cropped up, after the location and construction timeline of Target Field was announced, projected the construction of shops, condos, and other amenities in the area, but these plans stalled because of the economic meltdown in 2008. New stadiums built before the current bust times in Denver, San Francisco, and San Diego each had a marked effect on their neighborhoods, helping give rise to new condos, shops, parks, restaurants, and other new cultural activity. On the other hand, almost no development of any sort has happened around ballparks built in recent years in St. Louis, Washington D.C., and Houston. Indeed, Metrodome developers fully expected, after the 1982 opening of the facility, that all sorts of development would happen in its part of town — and we all know what happened with that.

Still, the economic slowdown hasn’t slowed down the crowds, nor has the lack of nearby parking. People are walking across the city, coming early to enjoy the stadium atmosphere, or they are biking to the stadium via the Greenway — making use of hundreds of bike parking spots around the stadium — or they are taking the light rail to Target Field Station. Currently, the rail comes from one direction, from the Mall of America and the Metro’s southeastern suburbs, but eventually lines will come in from the northwest corridor and the cross-town railway. A good initial sign of the positive impact of Target Field is in the fact that several nearby businesses have already transformed; Kieran’s pub has moved across the street from Target Plaza into an empty spot in Block E, and facelifts are apparent at Hubert’s Sports Bar (in the Target Center) and Champps (now called Smalley’s 87 Club). And many more nearby businesses have spruced up as well, adding sidewalk seating and decorated anew with Twins paraphernalia.

With all the crisscrossing rail lines and road lines running around and beneath Target Field, and marching squadrons of pedestrians coming from all corners of the city, the stadium fits into downtown Minneapolis perhaps not so much like the other new-retro downtown ballparks, but like actual, honest-to-goodness truly retro neighborhood ballparks, in honest-to-goodness walking cities — like Wrigley Field in Chicago, Fenway Park in Boston, Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Indeed, Target Field seems to resemble a great, lost treasure like Ebbets Field even more than the New York Mets’ Citi Field, which was purposely designed to resemble, at least superficially, the Brooklyn landmark that was demolished in 1960. Citi Field is located in a park, Flushing Meadows, removed mostly from the city, while Target Field, like Ebbets Field, is nestled into a busy city landscape. Ironically, Ebbets Field was doomed by its lack of room to grow and the dearth of parking on and around Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn in the 1950s, when the Brooklyn trolley lines were replaced by freeways and city dwellers began to escape the downtown areas to the newly developing suburbs. It’s a sign of the times, and a telling indication of how Minneapolitans want to live now that Target Field turns the pattern of the 1950s on its head, bringing the city masses right back to the downtown with the promise of a dazzling few hours in the city.

As if foreseeing that Target Field would become a city and regional showcase, the Twins made sure to take into account people’s expectations for the place. As a result, Target Field abounds with smart-design elements. For instance, Target Field goes to extreme lengths in catering to people with disabilities. Every gate in the park is wheelchair accessible, and 800 wheelchair-accessible seating areas have been set aside — in good, unobstructed areas of the park, with outlet boxes nearby to recharge wheelchairs batteries. Closed-captioning boards are available on the left and right field foul lines, and assisted-hearing devices are in every ticket window. Designers even went so far as to include some seats with removable armrests to accommodate larger fans. And I haven’t even begun to describe the environmentally friendly aspects of Target Field — the high-efficiency field lighting, heating and cooling systems, and interior lighting; the water-saving plumbing fixtures; the specially designed water filter system that captures runoff from the field for reuse; recycled building materials; and so on. It’s probably enough just to point out that Target Field is only one of two baseball parks to have been awarded Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Silver Certification from the U.S. Green Building Council.

It’s plain good oversight for voters to scrutinize public expenditures for such works projects. But one reason I have come to love the Twins, and a reason why I now endorse the public expenditure that became Target Field, is because the team exemplifies the best traits of Minnesota.

For all of these reasons, and more, Target Field is a fabulous addition to Minneapolis — so much so that even the most virulent opposition to its construction has been largely silent over the past few months. So popular is Target Field, that on March 22 the Twins announced the team had already sold more tickets, 2.5 million, in advance sales for this season than they sold during all of last season. So marked has been the increase to Twins attendance that, according to a Forbes.com article, without the Twins’ recent increase in attendance — from an average of 24,405 per game last year at the Metrodome to 38,382 per game this year — the attendance numbers for the league as a whole would be down two percent from 2009 (instead of being basically stable this year). With Target Field drawing significant numbers of fans to the game, and to the downtown Warehouse District, it seems likely at this point that the Twins will remain a boon not only to downtown Minneapolis, but to all of baseball.

III. Some Observations on What Target Field Represents, Symbolically, Not Just to Local Baseball Fans, But to All Minnesotans, Particularly in Light of the Public Controversies Surrounding Its Financing

By way of coming clean, I have to admit I’m a rather dedicated Twins fan, so it’s possible I may be ruining a hard-earned, long-standing reputation for even-handedness by writing such a glowing assessment of something I’m already prone to love. But in my defense, I was a Twins fan long before it was clear the team would have a new stadium, and I would have continued to attend baseball games at the Metrodome, as unfit as that venue was for baseball games, until I was too infirm to do so. I would also have embraced a new Twins stadium even if it had been rather poorly designed. So, this review is a product of my double joy at being able to wholeheartedly endorse the virtues of Target Field.

Certainly, the process it took to get Target Field built — more than ten years of lobbying efforts, the threat of a move to North Carolina in 1998, and a near-contraction in 2001 — was a challenge to the team’s values. Minnesotans are justifiably reluctant to throw public works money at construction projects intended to benefit only a particular audience. After all, it’s plain good oversight for voters to scrutinize public expenditures for such works projects. But one reason I have come to love the Twins, and a reason why I now endorse the public expenditure that became Target Field, is because the team exemplifies the best traits of Minnesota. “We’re from Minneapolis-St. Paul,” Twins president Dave St. Peter said long ago, when the Twins got widespread kudos for the design of the team’s spring-training facility in Florida. “We’re not playing in Boston, New York, or L.A. We’re proud of our on-field accomplishments, but … with the Twins it’s more of a grassroots approach. We’re more of a grassroots team.” Indeed, the team’s connection to the values of its fan base, and its willingness to listen to what people wanted in a new stadium, have been a large part of the success of the project.

Target Field is a reminder of what Minnesotans most value: Their neighborhoods, home-grown amenities, accessibility, thriftiness, long-term planning, patience, eco-friendliness, and all things local. Indeed, Target Field celebrates the team’s history, its locale, and the culture of the state of Minnesota. Throughout the park, inside and out, the Twins have made sure to decorate the confines with relics of the team’s history, and of the state’s history and culture. It starts from the very entry points, such as Target Plaza, where local artist Bill Mack has designed statues of great Twins players and moments in the team’s history, and where gate handles are in the shape of the state, and this ethos continues throughout. In the reception area to the Twins corporate office, there’s a whimsically colored, skewed, layered relief panorama of Target Field and its neighborhood by local artist Michael Birawer. In the private suites level of the stadium, in the hallways outside, the walls are decorated with a series of art exhibitions, more than 20 overall. These include a series of historic, early-century photos from the team’s history as the Washington Senators, a series of impressionistic portraits of the Twins’ managers, precisely drawn graphite montages by local artist Terrance Fogerty of key moments in the careers of Twins Hall of Fame players, mock baseball cards painted onto metal panels, and on and on. There is nearly as much art in Target Field, and as many styles of art, as you might find on one floor of a standard-sized museum.

The country would be much better off, if only other businesses, organizations, and institutions were as responsive to their constituents’ needs as the Twins have been. Indeed, it’s rare to find such socially responsible institutional values in our country today. The Twins’ values are put into sharp relief when you compare their approach to designing and constructing Target Field with several other recent construction projects of similar scope. In New York, the Yankees opened their new Yankee Stadium a year ago, but instead of creating an intimate urban park they built an incongruously large and bombastic structure that cost three times what Target Field cost — and they did so during a time of economic crisis across the city and around the country. Perhaps because of these factors — the exorbitant expense, the gaudiness of the structure, the attendant high ticket prices, even charges of graft and corruption in the construction crews (due to faulty cement that is already cracking) — reviews of the new Yankee Stadium have been, at best, mixed. And some reviews of Yankee Stadium, in eye-opening contrast to the glowing reviews of Target Field, are quite scathing.

Non-sports fans will often complain — and it’s hard to fault them when you see the sort of waste and greed and hubris on display at Yankee Stadium — that the public should not have to pony up for sports stadiums. At the same time, the Twins aren’t to blame for this; this sort of bargaining for dollars is just the way things are done in professional sports, and a team attempting to do things differently risks bankruptcy or being run out of the league. We’re fortunate that, to the Twins’ credit, the money for Target Field could hardly have been used any more effectively, intelligently, and thoughtfully than it was. You could easily compare the public money that the Twins used for the stadium (an amount estimated to be about $350 million, paid for by a 0.15 percent Hennepin County sales tax) to other large sums of money spent over the past few years on public building projects and conclude that the Target Field money was rather well spent.

For example, the Walker Art Center’s campaign for its recent expansion was for the amount of $92 million; the new Guthrie Theater cost a reported $125 million; and the new wing of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts cost a reported $50 million. While the sums used to shore up three local arts organizations are smaller than the money used for Target Field, I’d argue that none of these projects, once completed, exhibited the care and attention to the public trust that the Twins’ project did. Whereas the Twins vetted their designers carefully and chose a proven specialist to run the project wisely and frugally per the team’s Minnesota values, the Walker, Guthrie, and MIA each turned to top-name, out-of-state, avant-garde “starchitects” who were out of step with local values. As a result, all three structures suffer from a sense that they don’t care as much about their hometown patrons — namely, you and me — as Target Field does.

The Guthrie Theater, for example, with its long, sterile, and dark hallways, its endless escalators and frivolous bridge-to-nowhere, seems better suited to host airport passengers than theater-goers. Jean Nouvel, the theater complex designer, could have learned something from Target Field’s wide, inviting, and lively concourses, places where people actually want to move about and visit. I always feel I’m headed to baggage claim when I’m at the Guthrie, not to one of top regional theaters in country, and this is a shame. The Walker Art Center’s expansion also seems designed, by ubermodern Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, without people in mind. It starts from where they situated the museum’s new main entry-point — underground, in a dark and industrial hallway off an ugly parking garage — and it continues through the building’s confusing tangle of twisting, turning corridors and hallways and oddly shaped galleries. And as for the MIA, well, what good can one say about its addition? The new wing is a faux-classical structure of rather poor design that seems more appropriate to a small town library than a world-class urban arts center. The building’s chintzy woodwork, bland masonry, and pointlessly quirky geometry, sterile and boring exhibition halls, and lack of any kind of magic or gravitas indicate designer Michael Graves could have learned much from the simple elegance of a building clad in local, rough-hewn Kasota stone.

Symbolically speaking, then, Target Field is a monument to getting public works right by honoring the public trust and listening to what people want with an eye toward how visitors will actually use the space. As a result, Target Field shares many of our values: It is accessible, ecologically conscious, energy efficient, and it evinces a pride in local history and culture. The stadium is beautiful in surprising and modest ways — from the look of the local Kasota stone on its exterior to its interesting spaces and all the local touches of art and design inside. In sum, Target Field represents the best of Minnesota. It is a monument that everyone in the state can take pride in.

About the author: Michael Fallon has been hanging around the fringes of the Minnesota art scene for a good dog’s age, his career having run the gamut from exhibiting artist to arts writer for local and national publications and from exhibition curator to hard-working arts administrator. From these experiences he’s learned that people in the art world often take things too seriously. Michael believes one good solution for this is for artists and arts lovers to get together more often for happy hour, which is why he started organizing them a few years ago. See www.arthappyhour.com; www.facebook.com/art.happyhour; www.twitter.com/arthappyhour for details.