Remembering One’s Own: Answering the Call of Spirit

Poet and artist Ánh-Hoa Thị Nguyễn reflects on a project that began with a voice in a salt bath, and rippled through many art forms to honor the resilience and bravery of refugees.

If you quiet your mind enough, you will be amazed at what your body can sense in the flicker of a flame and the whispering waves of water.

In the early fall of 2017, a psychic friend of mine suggested that I take a salt bath to clear my body’s energy, which at that time was laden with worry from caring for a loved one living with cancer. I decided that since I was born in Vietnam and lived in the Bay Area for much of my young adult life that I would use Pacific sea salt instead of Epsom salt, which is called a salt because of its chemical compound, made up of magnesium, sulfur, and oxygen, getting its name from the town from the spring where it was originally found, Epsom, in Surrey, England.

As my head and limbs bobbed in the billowing bath, skin soaking in salinity, my half-submerged ears heard through the echoes of sea: a voice. It started as a hollow cry for help and then multiplied into a tide of wailing. The pleas that pierced my soul the sharpest were, “Don’t forget me. Don’t forget me.” At that moment a swell of tears streamed from the core of my nakedness and I sobbed and sobbed for the souls of spirits I could not save.

A few weeks after this experience I met with fellow artist, Sarah Peters, about her reccurring summer program The Floating Library, which is “a collection of artist-made books and printed matter aboard a raft, on a lake, accessible by boat.” As we bonded over veggie momos with spicy sauce at Everest on Grand, she asked me if I would be interested in collaborating with her as the Artist-in-Residence for her summer 2018 Floating Library at Lake Phalen in St. Paul.

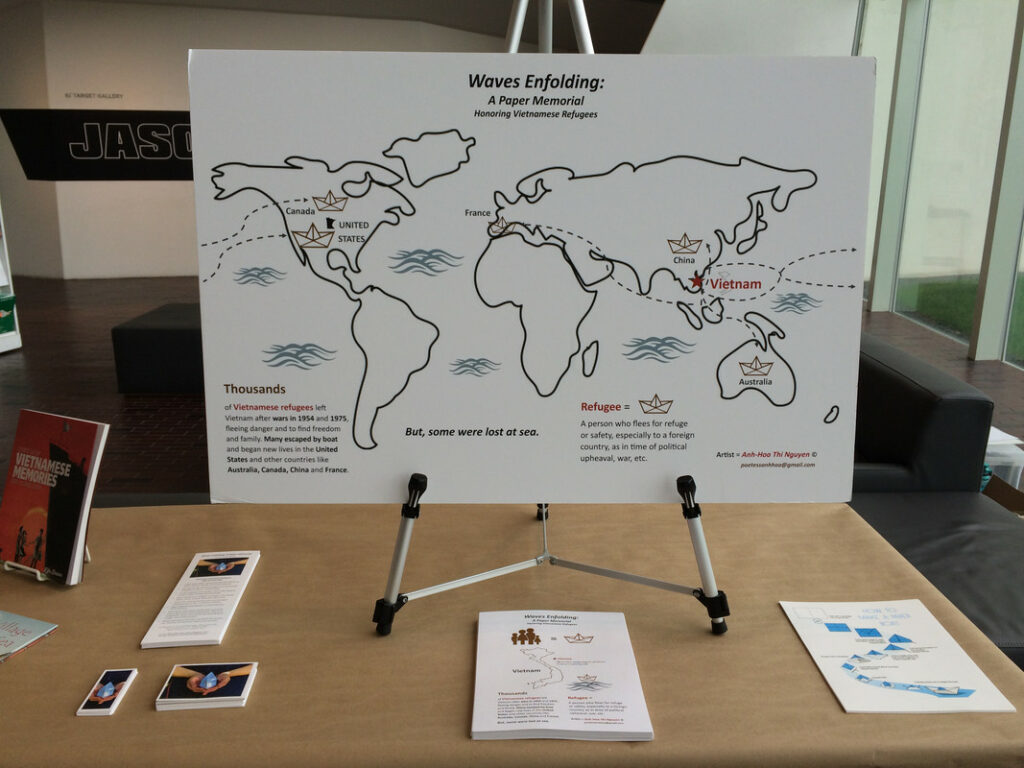

One of the requirements of my art project was that it had to relate to water, and I immediately thought of the voices I heard in my salt bath. I told Sarah that I wanted to do something to remember Vietnamese refugees that did not survive their escape from Vietnam. During our dinner I conceptualized my project “Waves Enfolding: A Paper Memorial”, with the goal to create a thousand paper boats to honor lives lost during the Vietnamese refugee waves of 1954 and after The War in Vietnam and South East Asia, 1975-1992.

“Waves Enfolding” began as a response to a spiritual calling to remember—and then expanded from a conversation with one person to conversations with hundreds of strangers, friends, colleagues, veterans, community members, politicians and loved ones from 76 locations in seven different countries, and the creation of over two thousand boats.

The initial concept for “Waves Enfolding” began with the theme of reflect and release. “Reflect” describes what water does, and this project was an invitation for people to look into themselves and discover how, like water, they reflect what is happening in their communities, and in effect, our society. The goal was to cultivate a ripple effect of these reflections. “Release,” a term associated with the casting of boats into the lake, evokes healing and the act of releasing losses, scars, grief and painful histories into the water, in order for them to dissipate.

It was important for me, as an artist and scholar, that I share the history and missing narratives of the Vietnamese diaspora with my communities, and over a four-month period, I invited the people of Minnesota to join me in numerous boat-making workshops utilizing portable artmaking stations, as well as a resource library sponsored by the Minnesota Humanities Center that offered access to books and films about the Vietnamese diaspora and refugee waves.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Photo courtesy of the author.

Photo courtesy of the author.

By sitting and folding paper together, participants created a representation of a person that was unaccounted for—father, mother, sister/brother, baby—while prompting a consideration of the refugee crisis that is currently taking place on other waters, in other boats. This project not only increased awareness and understanding of the multi-faceted complexity of the Vietnamese refugee experience, it created space for other diasporas, communities and children to connect through their cultures’ shared crossings and sacrifices.

The culmination of this project closed with a “Read and Release” healing ceremony and poetry reading on the shore of Lake Phalen, where some of the blessed boats were released into water.

Being a refugee is challenging, and often means that, as a refugee, you and your stories are invisible.

My parents, like many migrants and refugees today, faced intersectional challenges from being foreign and displaced, and endured racial prejudice and discrimination, poverty, lack of education and English language skills. Separated from their countries, they sacrificed everything—their homeland and their families—to protect their children. Like others who came to the shores of the United States before and after them in search of freedom, they had to make life or death decisions. Their resilience and bravery, and that of the lives of the lost refugees this project honors, makes me grateful and proud to claim my authentic self as a Vietnamese refugee.

This piece is part of the series by guest editor Sun Yung Shin.