Paj Qaum Ntuj / Flowers of the Sky

On the multivalent meanings of the term "Flowers of the Sky"—landscapes of desire, the cost of dreams, and the great green exodus

There is a Hmong business in the Twin Cities called Paj Qaum Ntuj. Flowers of the Sky. Nao Her makes decorative joss paper arrangements for funerals. She first folds the papers into gold and silver boats and then arranges them in 3D structures of hearts, stars, jars filled with ornate towers, and upon request: horses, houses, and ships of varying sizes. These structures are tokens of love for the deceased. Before the burial of the bodies, they are burnt as offerings so that they might accompany the beloved into the Land of the Ancestors.

Previous to my knowledge of the business, I understood Paj Qaum Ntuj to be the actual flowers of the sky. I recall a Thai film I experienced as a child: a movie in which a beautiful sky maiden is captured by a human man and turned into his wife. After he breaks her heart, she journeys back to the heavens. He chases her there on the wings of a mystical horse. He finds her in a garden collecting the early morning dew from the petals of white flowers. I understood Paj Qaum Ntuj to be like the ones in the movie: big and bold and bountiful, in glorious bloom.

I should say here that for me the Sky is a real place, though it exists beyond a measure of geography. It is the space of ancestral reunions. It lives somewhere between the American notion of heaven and the Hmong understanding of an Afterlife. It floats above the highest clouds; it is individual and it is all-encompassing at once, a moment that lingers and loves endlessly, a generous figment of time that continuously gives and forgives as a site of eternal belonging. It is a place both fragile and strong, very much like the most elusive of flowers that bloom across the spaces we know, the places we cannot inhabit, and the landscapes of our most verdant wishes and desire.

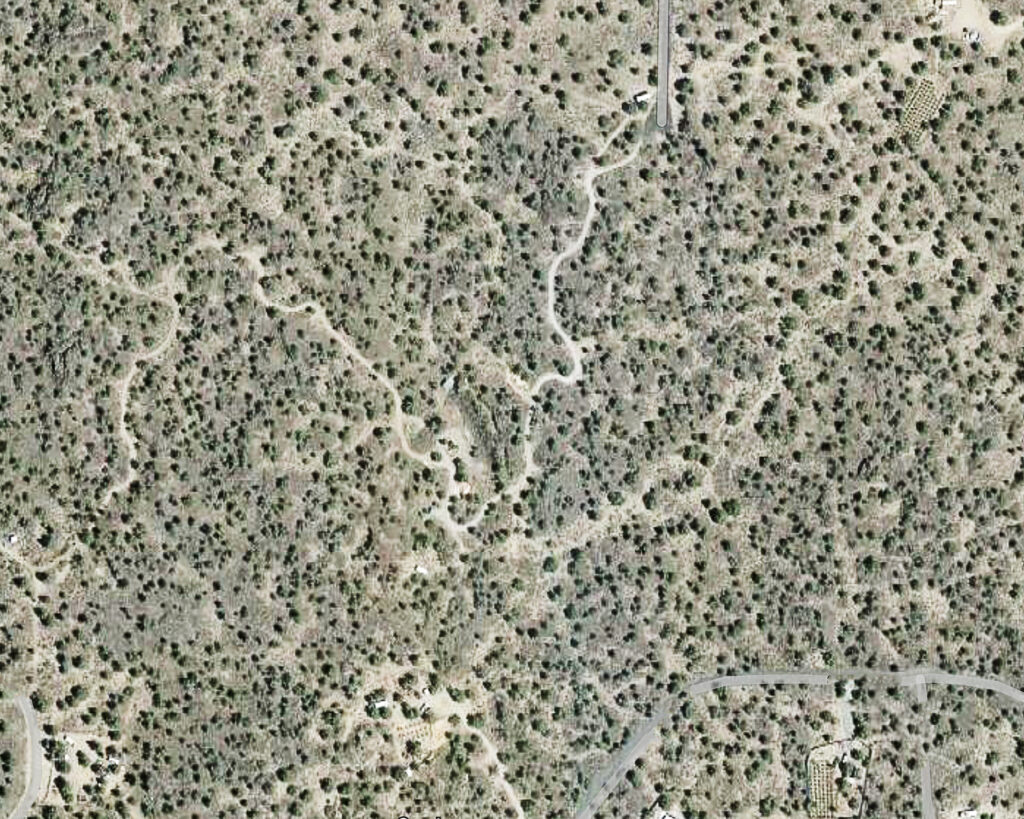

I was quite comfortable with the notions from my childhood and the practical existence of the business until two years ago, when I learned the new and popular definition of Paj Qaum Ntuj as cannabis flowers. New winds were blowing across my community. Whispers abounded. How many do you pick in a day? How much do you make? Do you sell it by the pound? And where do they sell it to? Guns. You carry? They carry? Everyone carries. Friends and neighbors disappeared one by one, fueled by a need to harness their fates beyond the confines of the capitalist clocks, swayed by the power of the whispers. People living from paycheck to paycheck, elders and other disabled folk who were unable to find employment, individuals without English proficiency and the young and enterprising, individuals who believed in their own industry, all started moving to previously unknown territories in California, Oklahoma, and Oregon, among others.

I had been in the United States since I was six; the landscape of my world was Minnesota. I’d seen the movies and read the articles about the different movements and marijuana, the medical reports and the cultural headlines. I understood the changing nature of our laws and perspectives. I worried about the people who were leaving Minnesota behind, taking out their life savings, and dreaming big dreams. I remember the seduction of the gold rush stories and then the tragedies that resulted from prohibition, seen how the changing laws of this country could make a good person bad, could turn a vulnerable community into the potentially powerful. I knew the continued injustices against newer groups for attempting to leverage their fates beyond the circumscribed.

And yet: there was nothing I could do or say in the wake of the strong storms blowing my people in different directions. The only thing I was going to say was, be careful—but those of us who’ve been paying attention, we know that no amount of care accounts for racist and prejudicial practices and institutions. The only other thing I was going to say was, Asian hate is real—but how would that be new to anyone I knew and loved, everyone who had survived so much hate to get here, to this country already? The truth was simply: I knew very little beyond the parameters of my own life, my artistic pursuits, and the more important matter was the simple fact that we all needed inspirations and ideas, a way of believing that the happy endings of our lives were still possible. My community was poor. According to the U.S. Census we are among one of the most impoverished in this nation, the most linguistically isolated. Besides, we carry a long and proud history of tilling the land. If the green rush was a plausible pathway forward, wasn’t this—like the other rushes in history—a tremendous turning point in who we might one day be?

In the pursuit of Paj Qaum Ntuj, we were left with dreams. Both for those who traveled in search of them and those who stayed behind. The dream that one day we would be together again, in a place where we were respected, where we were loved. The dream that we would one day soon have enough financial clout to warrant some care from those who did not know us or love us. The dream that all the dispersing would just bring us together again, tighter and closer, than we were before.

In the pursuit of the Paj Qaum Ntuj, we were all just left with the nightmares. There were reports of Hmong cannabis farms getting bulldozed in Siskiyou County. Others of lava fires destroying Hmong pot farms in Weed, California. Individuals dying from carbon monoxide poisoning in an effort to stay warm while tending to the farms. Young people were shot and killed by other forces and police alike, among them Soobleej Kaub Hawj, a 35-year-old, shot and killed on June 28, 2021. It became clear in the great green exodus that the dispersal would be permanent.

There is a saying in Hmong about the separations caused by the earth and the sky. Those who adventure in one direction cannot turn back to the other. What begins as choices become decisions and these are the true markers of one’s life trajectory; our decisions decide who we walk with, who we race by, who we wait for, who we carry, who we fail, and how we fall.

The proliferation of Paj Qaum Ntuj at funerals has grown significantly over the last few years. In the last two years, the presence of COVID-19 and its harsh and disproportionate impact on our community has touched every Hmong family and altered our numbers and our hearts. Funerals have always served as gathering grounds for community. Now, we sit staring ahead at the gold and silver joss-papered flowers alongside the bodies of our loved ones. We sit beneath the glow of the electric lights that bring out the yellow in our skin, the pallor beneath our eyes, the streaks of our tears. Paj Qaum Ntuj, like that of my childhood, grace the photographs of the deceased. They stand sometimes on stars leading toward the clouds, and at their feet the flowers bloom in wild abandon.

Pao Houa Her’s exhibition Paj qaum ntuj / Flowers of the Sky is on view at the Walker Art Center July 28, 2022–January 22, 2023. >> more information