One in the Hand – Zak Sally and La Mano Publishing

Matt Konrad sits down with former Low bassist -turned-comics impresario Zak Sally to talk comics, indie publishing, and the ins and outs of making a living at art without adding trash to the cultural pile

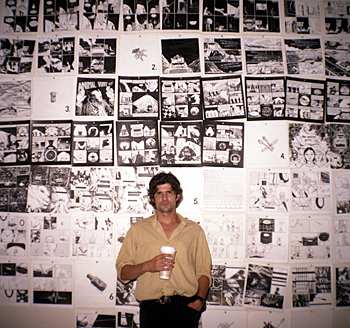

THE NORTHEAST MINNEAPOLIS BUILDING HOUSING THE studio and office of Zak Sally’s publishing concern, La Mano 21 , is maybe the most fitting possible home for the not-quite-comics, not-quite-prose, not-quite-cult, not-quite-mainstream artist at work.

It’s a block-square white brick rabbit warren that started life as a military installation, housing dozens of artists at work drawing plans for experimental weapons and aircraft; to get to Sally’s studio and what passes for the La Mano warehouse these days, there’s a long-ish hike down an alley, past a WWII-era watchtower, up a flight of stairs and through—no kidding—a blast door.

And while nothing that Sally is doing may have quite the dangerous impact as, say, a prototype of a laser ray, the fact is that La Mano is something of a grand artistic experiment in its own way. Sally, a quiet, thoughtful guy with a quick smile, is a long-time comics fan and creator of ‘zines—those photocopied, do-it-yourself publishing forays that indie-culture fans remember fondly. But he’s best known for his last gig as the bass player in the understated Duluth rock band Low . Nowadays, he’s attempting to bridge a whole lot of long-standing gaps: between books and comics, between do-it-yourself and professional publishing, and between working at a labor of love and making a living.

“The stuff that really, really turns my crank is the stuff that’s not one thing or the other, or doesn’t necessarily have to be one thing or the other,” Sally says over a cup of coffee in his studio, discussing the rigid genre divisions he’s trying to help overcome. “Culturally, those distinctions get really oversimplified. ‘Oh, this is a comic book, so it’s this.’ ‘Oh, this is a zine, so it’s this.’ I’ve never seen it that way, and I don’t think a lot of people see it that way.”

“I am a total nerd, I love the comics form so much, but it’s not like that’s all I read, or that’s all I’m interested in, and I think most people are the same way. So when the stuff comes up that’s more confusing, that’s when I get really excited. And I think the stuff coming down the pike with La Mano, if it happens, is pushing that a little bit more.”

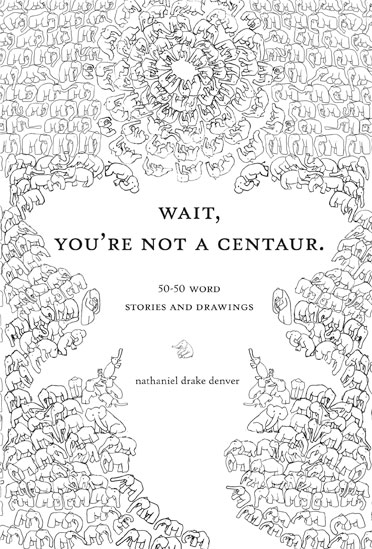

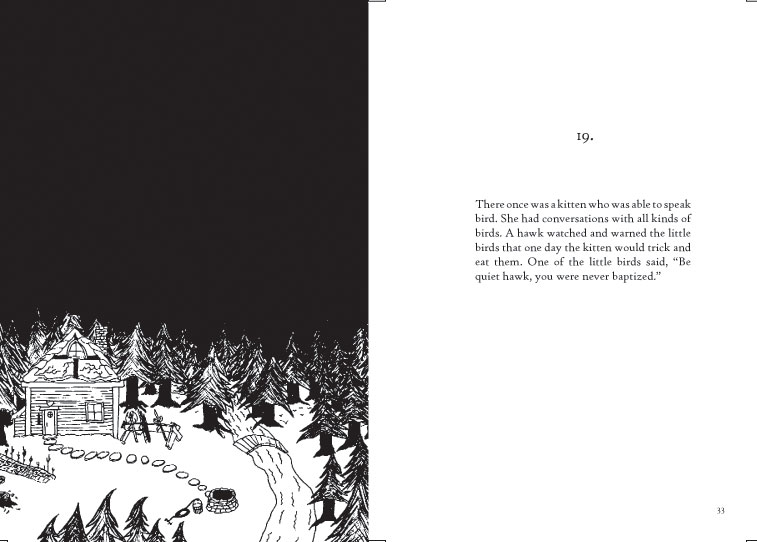

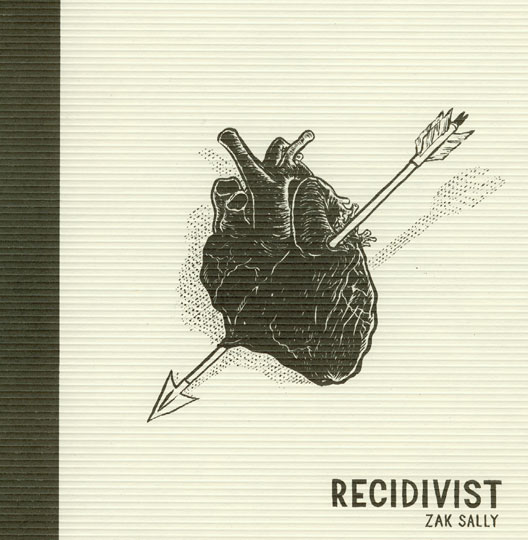

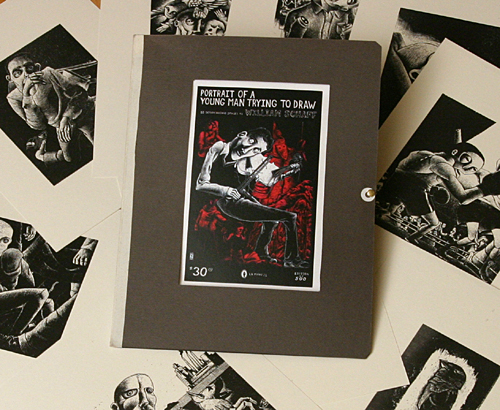

A look at La Mano’s current lineup, made up largely of former ‘zinesters and musicians, confirms the wide range of that path. First, there’s Sally’s own book, Recidivist , a collection of detailed, inscrutable mini-comics in which husbands may or may not keep wives chained in the basement and businessmen with animal heads wander into mysterious hospitals in search of a cure. John Porcellino ’s Diary of a Mosquito Abatement Man , by contrast, is a simply drawn autobiographical collection addressing the author’s work tales, health issues and relationship with nature. Another new La Mano offering, Nate Denver ’s Wait, You’re Not a Centaur , collects a bunch of surreal, speculative 50-word stories and pairs them with crude but fascinating line drawings.

In short, while most publishers would give anything to be known for a single narrow niche, Sally’s going the other way and striving to be pretty much unclassifiable—except insofar as he’s passionate about bringing to a larger audience the kind of good but odd work that tends to fall through the cracks.

“A lot of smart, savvy people—and this is changing—but ten years ago, you’d put a comic book in front of them [and they’d think] ‘this is a fuckin’ joke,’” he says. “Some people are not gonna take it seriously on some level. A ‘zine even less so. And that’s just not true. There’s stuff that has happened, and that is happening, in the ‘zine world that kicks the shit out of most literature. The same with underground comics—a lot of ‘em, the sheer quality is so much better. [Doing La Mano] makes me feel like I’m not just adding to the pile of garbage.”

It’s hard to argue with the quality of La Mano’s output thus far. Sally’s on a mission to get unknown good work out to a wider audience. Porcellino’s Mosquito Abatement stories are almost impossibly touching, self-aware, and vulnerable in the face of the natural world in the way of, say, Wendell Berry’s essays; Sally’s Recidivist work calls to mind underground legends like Chester Brown and Charles Burns with its mix of black humor, dark panels and unsolvable mysteries. When he recalls the process that went into its creation (he’s now retired from drawing the Recidivist strips), it becomes clear just how devoted Sally is to putting quality art into the world.

“[Recidivist] was awful,” he says, while discussing his new project. “While I was doing it, it was, like, either I’m gonna finish this thing and quit comics, or I’m gonna finish this thing and find a way to do something else, but I have to get it done. I finished it, and I decided I don’t have this compulsion to do that anymore.” His new project, incidentally, is a massive undertaking that Sally remarks mordantly “is probably suicide”—a multiple-installment, four-hundred page tale of a cartoon mouse, commissioned by Italian publisher Coconino for an imprint that distributes comics in multiple languages in six countries. Despite the size of the task ahead of him, though, Sally’s looking forward to it. “I kind of buried myself in [Recidivist], and now it’s done. Now I get to draw mice and ducks, thank fucking God. I’m now actually having a good time doing this.”

His sense of relief at enjoying cartooning again is palpable, especially given the sheer amount of work that goes into running La Mano—“I don’t have time to scratch my ass, I can’t write a grant proposal,” he laughs, mentioning the unexpected challenges that go along with moving from hobbyist to businessman. He also mentions ‘zine elder statesman Aaron Cometbus , the force behind the hugely (well, in context) successful Cometbus ‘zine.

“I asked him once how he did it, and he said ‘I just hustle.’ You just move your ass, constantly. It seems like that’s what you have to do, you can’t afford not to,” says Sally, aware as he looks around the La Mano office that, no, it isn’t easy. “That’s an artist thing. ‘Oh, if it’s good, people’ll find it.’ Bullshit, they will, you snotty bastard! Who do you think they are? For me, with other people’s stuff, especially, it’s just, like, ‘look at this! It’s amazing!’ You have to do that, and you have to do that in a way that’s honest. I might have had some of that artistic ethic when I started in Low, [but] you can only have that ethic until you do it. This is work.”

And, taking a look around the fortified compound that houses his office, it’s clear—from the pages tacked to the walls, to the stacks of boxes, to the space that his printing equipment recently outgrew—that Sally both understands and relishes the effort required to find a new way of distributing good art.

“My hope is that it can all be somewhere in the middle,” he says. “I’m a printer, but I don’t want to be a real printer; I’m a publisher but I don’t want to be a real publisher. Somewhere in between it all is where I’m ending up. And I like it a lot, except for being really fucking broke. I run into frustration, but I really like making these books, and especially the people I work with. People whose work I love personally, people I love personally—I love making that book be available. Turning that into a real thing that people can hold in their hands is one of the greatest feelings I know of.”

La Mano 21 titles are available, among other places, at Magers and Quinn Booksellers and Big Brain Comics in Minneapolis, and through www.lamano21.com.

Matt Konrad is a writer in Minneapolis. He blogs about life, culture, sports and whatever comes to mind at The Cash Box. (cashbox.livejournal.com)