Massive Mint Competition: Altoids Wants You

"The 5th Annual Altoids® Curiously Strong Collection" has its Minnesota debut at the Soo Visual Arts Center, May 19 - June 19, 2003. Andrew Knighton speculates on what this all may mean. . . .

There’s been a lot of talk in the mainstream press in recent weeks about the ever-evolving relationship between business, money, and culture. Amidst that talk have been the inescapable laments about Texaco dissolving its sponsorship of the cherished Saturday Metropolitan Opera broadcasts, and the celebration, in the New Yorker, of the return to patronage spearheaded by the Dia Foundation; together, these episodes indicate some dramatic reconfigurations of the ways in which high-profile artistic production is funded and supported. But while such tectonic shifts in the funding terrain have grabbed headlines, a much less obtrusive initiative is suggesting new possibilities for cultivating and promoting visual artists at a more grassroots level. Playing Lollapalooza to Texaco’s Met, the Altoids®’ Curiously Strong Collection is a touring exhibition of “emergent” contemporary artists that fuses arts philanthropy with marketing gimmickry. The collection’s visit to Minneapolis is occasion for us to explore the future path in arts funding that it seems to chart.

Here’s how it works: in each of the past five years, Altoids has convened a curatorial committee comprising experts from around the country. For this round, the local scene was represented by the Walker’s Douglas Fogle, who joined a roster of curators that has in the past included such figures as Jeff Koons and David Hickey. Charged with identifying artists whose work is “curious,” “strong,” and “original,” this curatorial task force nominates and selects a small selection of emerging artists — this year there are twenty, with varying degrees of career exposure — and Altoids funds a nationwide tour of their work.

The Soo Visual Arts Center, slotted into the tour between its stops in Seattle and Miami, was selected, on Fogle’s recommendation, as the local host for the show. Soo Director Suzy Greenberg welcomed the opportunity, both because the show brings in national-caliber work on a scale that the gallery wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford, and because, save for the actual hanging of the pieces, much of the labor of staging and promoting the show is handled by Altoids. Above all, according to Greenberg, the Altoids Collection is distinguished from a “typical corporate collection” by the crucial role of the selection committee, which reflects the prerogatives of the art world and of the localities represented. The acumen of these art insiders is what shapes the show: “This is about respected curators,” Greenberg says. “And what impresses me most in all of this is the level of trust that Altoids places in these curators.”

The ample publicity machinery accompanying the collection is likewise a boon to the galleries and artists involved, generating a degree of “visibility” and “exposure” that is nearly unique to this project, according to Gigi Garcia Russo of Hunter Public Relations, the firm that has organized the initiative. Greenberg adds that “Altoids is not just buying the works, but is actually working for the artists,” touring their pieces around the country and introducing them to new audiences through active promotion. That promotion included a half-page ad in the City Pages which has attracted a different, larger crowd to the gallery.

We shouldn’t be surprised that there is something in all this for Altoids as well — this is, after all, a promotional campaign orchestrated to serve not only emergent artists and local scenes, but also the interests of the tinned-mint manufacturer. And thus, while the media kits issued by Altoids emphasize how the Collection is “designed to help emerging artists garner national recognition,” those issued from Hunter Public Relations — targeted at the PR industry and the clients it serves — tell quite a different story. There we find that the Altoids Curiously Strong Collection was developed “to help maintain Altoids®’ relationship with hip, urban, early-adopters in the face of massive mint competition.” One characteristic of that audience, as Soo’s Greenberg notes, is its indifference to corporate pitches: “the people we get here are smart; they aren’t so much interested in or influenced by advertising,” she says. Hunter therefore suggests that these desirable core users — “the highly educated and hyper-social” — are best reached more subtly, by Altoids “showing up in places that are relevant and important to their culturally engaged lifestyles” and through the generation of “media coverage in specific alternative and lifestyle media outlets.”

It is precisely the brilliance of the Altoids collection that it conducts a form of advertising that doesn’t feel like advertising, and is thus all the more effective with its target audience. Russo stressed how Hunter initiatives like the Altoids Collection, or the similar Curiously Strong Public Art project (which provides public permission walls for street art) are “totally unbranded. There are no artists creating works for us — we’re highlighting the artists and not ourselves.” But the apparent autonomy enjoyed by both the artists and the curating committee is belied to some extent by Altoids’ selection criteria, which stipulate that “most importantly, the work needs to reflect the Altoids curious, strong and original personality.” Forget those dusty cliches about the sublime and the beautiful, there’s a new regime of aesthetic evaluation in town. It is based upon the flavor of mints.

It was about a century ago that the basic strategy behind advertising shifted away from making claims about the usefulness of a particular product and toward promising that buying it would bring sex appeal, prolonged youth, familial harmony, and other, more intangible desires. But today’s marketing strategy is less about conveying a message than about fostering environments and scenes, and cultivating the specific types of individuals — in this case “the highly educated and hyper-social” — who inhabit them. Thus is created a unique demographic “effectively aligned” with the Altoids ideal, and which shares a standard of judgment conducive to profitable consumerism. It’s not surprising when SooVAC Administrative Assistant Emily Johnson observes of the Altoids-driven audiences for the show that “everybody asks if the work is for sale.” But these works have already been bought by Altoids, and rather cheaply at that (Altoids sets a price limit of $2,500 for works in the collection). Donating the work at the end of the tour spares Altoids the burden of storing and maintaining (or perhaps “caring for”) the works, except during the period when they travel around and build Altoids’ core demographic.

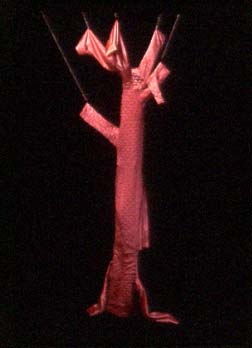

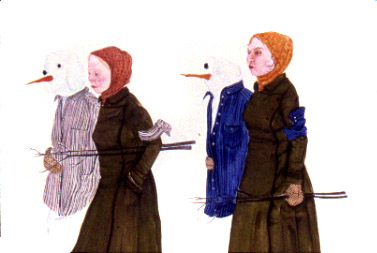

Even if you don’t accept the aesthetic integrity of interpretive categories like “curious,” “strong,” and “original,” you must conclude that Altoids has found itself a bargain; some standout works make the show something more than the unthematized curatorial hodgepodge it would seem destined to be. Local favorites David Rathman and Jay Heikes are represented here, as well as artists from Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, Miami, Portland, and elsewhere. While a number of the works drip with forced hipness or else flaunt an indifferent assortment of pencil scratches, glue blobs, and grease stains, the strongest works are as varied as their artists are geographically disparate. Jeff DeGolier’s Clevicsville is a collection of nine black and white prints, each with a small color insert (or two inserts, in one case), that record a desolate urban topography composed of nails, scrap, screws, and debris. The interplay of the larger panels with the smaller, color, ones at first suggests two different planes, but the arrangement of prints on the wall (one large square composed of smaller squares, each pocked by the square inserts) raises the possibility of subsequent levels of inserts, infinitely regressing in the inverse proportionality of their detail to their size.

Another play on space is conducted in Lordy Rodriguez’s Idaho, a fantastic map drawn on paper with colored inks, designating, at the geographically impossible convergence of Tennessee, Nebraska, and North Carolina, a region where the cities of Falcon Heights, Blaine, and Arden Hills appear just a stone’s throw from those of Scranton, Oakland, and Leavenworth. William Cordova’s large ink and pencil drawing (No More Lonely Nights) presents an imagined utopia of a different kind, depicting, in the middle of a vast white space, a hot air balloon loosely freighted with an array of consumer goods (sport and stereo equipment, furniture, clothes and bedding). Adrift in the midst of so much alienating negative space, Cordova’s balloon reads as a cautionary lesson about the false promises of transcendence made by consumerism.

There is also much to be said for the charm of Patrick Jacobs’ Living Room Corner, #11, a small eyepiece in the wall that beckons you to peer through its convex lenses onto a miniature replica of a room’s corner, its hardwood floors and baseboard molding naked save for a few mild rays of light. Jacobs uses paint, mirrors, and light to not only heighten the voyeuristic effect, but also to stir up confusion about how the effect is achieved. Being unable to distinguish between wood and paint, one is flummoxed by the simple illusion that questions whether what one is looking at is actually what it says it is.

Being jarred in such a fashion by the reality behind a carefully-manipulated appearance is, in a way, the story of this entire Altoids Collection. Its market-niche publicity, intended in no small part to stimulate media buzz, generates a catch-22 in which attempts at criticism only magically further its agenda. It is almost possible to ignore, in the thrall of the show’s redeeming qualities, that contemporary art stands ready to join “boutique” hotels, “alternative” music, and the other neglected love children spawned by the lusty union of business and culture. Altoids’ radical and aggressive strategy demonstrates the truth of the Adornian warning that “something is provided for all so that none may escape,” and, looking over the roster of Hunter’s other clients, one can hardly help but feel that the future possibilities of such marketing micro-strategies are all but infinite. Perhaps next year will witness a Pepperidge Farms Puff Pastry Soft Sculpture Series, if not a somewhat less savory sponsorship, of Serrano’s Piss Christ by Swanson’s Broth. What is certain, however, is that you — artist, art lover, critic, reader of this feature — are now one of the “over 120 million highly targeted impressions” that Hunter’s website boasts of having generated through the Altoids Collection, and that this curious marketing strategy has only just begun to prove its strength.