Local Talent, European Style: David Ericson at the Tweed Museum

Thomas O' Sullivan writes on David Ericson, a Duluth native whose work is the subject of a retrospective at the Tweed Museum in Duluth

“I only work with dead artists,” a distinguished historian of American art once told me. “They’re so much easier to deal with.” Honest or arrogant, she was unusual only in her frankness: her boast is something many in her profession subscribe to, but few are likely to admit. I’ve often had occasion to recall her words over my years of work in the dead-artists branch of the museum business, but I don’t agree with her. The silence that makes dead artists more amenable to scholarly manipulations can make them maddeningly unenlightening as sources of past wisdom. For better or worse, it leaves the last word to curators, historians, and journalists.

An exhibition at the Tweed Museum of Art at University of Minnesota-Duluth offers an exercise in listening for wisdom from history. David Ericson, Always Returning: The Life and Work of a Duluth Cultural Icon unfolds the stylistic development of a painter who largely ignored modernist fashions once he had found his direction. The show also offers historical perspectives into the phenomenon of “local artist,” interpretations that are worth pondering by members of the mnartists.org community who live that label today (whether it is self-proclaimed or applied by critics).

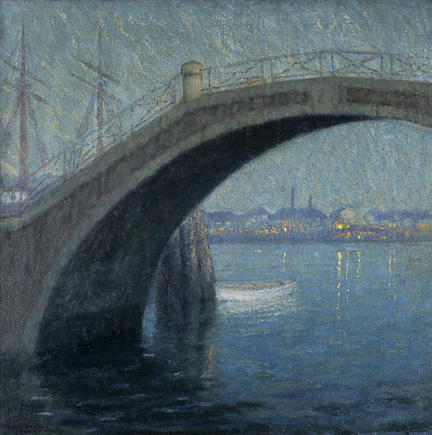

Easy on the eyes, Ericson’s small and mid-sized canvases from the 1880s to the early 1940s are comfortably bucolic or genteel in subject matter. His life story is the stuff of American legend. Born in Sweden, Ericson (1869-1946) was brought to Duluth as a boy and grew up on Park Point. He dabbled in watercolors while bedridden with an ailment that resulted in the amputation of his leg; by the age of 16 he won a gold medal in the Minnesota State Fair’s Fine Art Exhibition for a genre painting called “Salting the Sheep.” Duluth patrons sent Ericson to New York for studies at the Art Students League, the preeminent professional school of the day. By 1900 he was in Paris, refining his art in the ateliers of French masters and finally of James McNeill Whistler, whose pearl-toned reveries gave Ericson a lifelong aesthetic for his preferred themes of seaside vistas, quiet villages, and pensive sitters. Plein-air work in the south of France heated Ericson’s style to a boldness of palette and touch that was a veritable homage to French Impressionism; by the final decade of his life he had perfected a process of thickly worked surfaces glazed with transparent colors to achieve what he characterized as “a dreamlike quality.”

Ericson spent nearly twenty years of his life in Europe: living in France, traveling across the continent, painting in Venice. He owned a home in the Cape Cod artist’s colony of Provincetown, Massachusetts, and exhibited his paintings nationally to some critical acclaim. Ericson adopted the imperious Whistler’s style but not his attitudes: alongside his master, Ericson must have seemed utterly bourgeois. In Provincetown he seems not to have moved in the colony’s more adventurous circles, either artistically or socially, preferring a quiet salon of music and conversation at home with his wife and son and selected guests.

He accepted commissions for portraits of Duluth citizens and for altarpieces and murals, bringing the flavor of his tonalist and Impressionist modes to the best of his work for hire in northern Minnesota. But those same commissions made it possible to put some distance between himself and his Duluth roots, for years at a time. When a commission from Hibbing High School for six mural-sized canvases of American and local history paid him $9,000.00 in 1923, Ericson promptly left for an extended residence in France.

The cachet of foreign study and residence was enough to cement Ericson’s role as a de facto ambassador of culture to his home town. His exhibits in Duluth or other cities were noted with pride in local newspapers; he readily found teaching positions in the city. Duluth was clearly proud to have among its residents an artist who claimed acquaintance with not just Whistler but author Stephen Crane, the admired American Impressionist John Henry Twachtman, and other notables of early 20th century culture. How generously Duluth and its cognoscenti rewarded Ericson is another matter altogether. It is clear that he struggled for sales; in an uncharacteristic show of exasperation he wrote to the industrialist and art collector George P. Tweed (who never bought Ericson’s work), “You are of course buying names [i.e., famous artists] but even in that, I can assure you that mine stands as high as the best.”

The parameters of success in the arts are mysterious and rarely stated: for an artist, a musician, or a writer, the home town is often the place where you have to keep proving yourself. Had Ericson never left Duluth, even had he developed the skill and style that made “an Ericson” a valued commodity there, he would be an unlikely candidate for “cultural icon” status.

The dilemma neither started nor ended in Ericson’s day. A decade after his death Cameron Booth, another underappreciated veteran of the “local artist” conundrum, told a young Minneapolis student who was earning his tuition by painting ads on barns to go to New York for opportunities that would match his potential. James Rosenquist took his elder’s advice. Soon Rosenquist was painting billboards above Times Square to pay the rent, and applying his skills to canvases filled with fractured consumer-society images. His paintings became a canonical part of Pop Art, essential to modern art collections like those of the Walker Art Center and Weisman Art Museum.

George Morrison, like Ericson an artist with Lake Superior roots and ample representation in the Tweed collections, provides another case study in local fame awarded only after long and far-flung work. This paradox of earning attention at home by succeeding elsewhere will be familiar to all too many artists working in Minnesota today (and, no doubt, tomorrow).

Did “always returning” equal “never escaping?” In Ericson’s case, Duluth was a fixed point to start from, to return to, rather than a home place to illustrate or conquer or reject. His example gives the lie to our popular notion of artists as tortured souls whose price of fame is madness, suicide, or at least a severed ear. A Minnesota Public Radio reporter asked me why Ericson’s art looked so beautiful and often upbeat, implying that it lacked the authenticity of suffering. Only the artist could answer that with authority, and it’s too late to ask David Ericson now. Instead, we can accept the evidence of our senses as proof that he chose to paint pleasure, wonder, and dreams as his themes. The Aerial Lift Bridge, Duluth’s signature subject, is absent from the show; the bridges of Venice, rendered in Ericson’s brooding twilight style, resonated more strongly with him.

The Tweed’s intent in this exhibition is explicit its handsomely illustrated catalogue: “In celebrating the artist David Axel Ericson,” writes curator Peter Spooner, “we celebrate the extraordinary talent of a poor immigrant, a sickly local-boy-made-good who rose to become the cultural icon in the field of visual art for northern Minnesota at the end of the 19th century.” The choice of the term “icon” is telling. It calls up the memorial and devotional aspects of the kind of religious pictures that Ericson himself painted on commission for a Serbian Orthodox church in west Duluth. In our digital age, the term has the added connotation of an interactive shortcut to a world of wider associations, deeper meanings, and potentially endless contacts—a potential that David Ericson embodied for those who bought his paintings, took his classes, or just shared the streets of Duluth with a man who knew Whistler.

David Ericson, Always Returning: The Life and Work of a Duluth Cultural Icon is on view at the Tweed Museum of Art, University of Minnesota-Duluth, through January 15, 2006.