Life in Tom Arndt’s Minnesota

Mason Riddle offers a thoughtful critique on the retrospective of Tom Arndt's extensive body of work in light of the ongoing exhibition, "Home: Tom Arndt's Minnesota," on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through August 23.

I HAVE NOT ALWAYS APPRECIATED ALL OF TOM ARNDT‘S PHOTOGRAPHS. At times, I found certain of his images to be too emotionally blank and, ultimately, too ordinary to be compelling. Viewing the work, it was as if a clock began to tick in the back of my mind, reminding me it was time to get on with it, to find something more exciting to observe – wishing, for heaven’s sake, that he’d find more dynamic people on whom to turn his lens. But my perception of Arndt’s work has changed over the years. I now recognize the telescopic power of his eye, even if I’m still not particularly keen about certain works. I also realize, where I once did not, that his vision is about that abstract notion: time, the recording of time, and the patience required of the viewer, literally, to see.

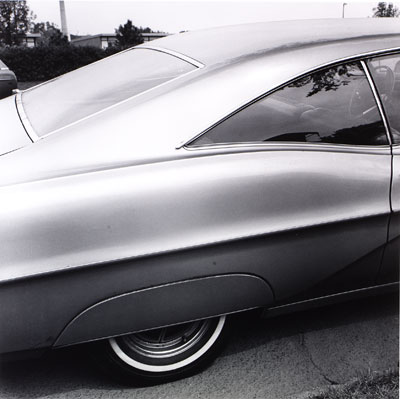

Black and white and of modest scale, Arndt’s images are an iconic window into a world of everydayness. His images are records, each as if a page torn from a visual diary, which reveal in excruciatingly bland detail the normalcy of the subject at hand, usually people. Arndt is also known, of course, for landscape photographs and his images of political conventions, both of which offer up either more beauty or more animation; but, largely, Arndt documents the most ordinary of people and events, a chronicle effortlessly conveyed in his exhibition of 80 images, Home: Tom Arndt’s Minnesota, currently at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The accompanying, handsomely designed book by the same title gives a more complete overview of this subset of the photographer’s body of work, featuring 157 photographs and essays by Arndt, Garrison Keillor, and George Slade that effectively construct a context for the images.

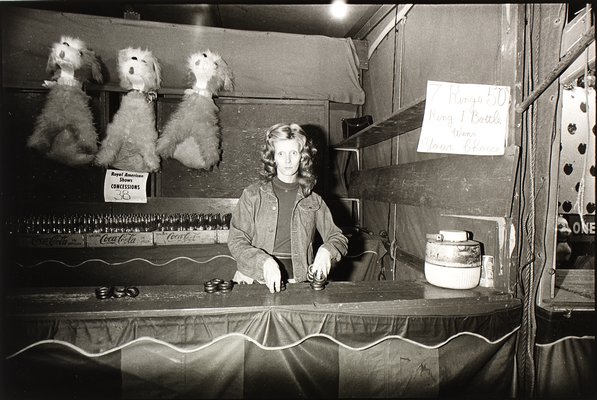

Born in 1944, Arndt has been taking photographs for over four decades. His documentary work is part of a lineage that includes August Sander, Robert Frank, and John Szarkowski; and Arndt, in fact, worked with Frank at one point and held the same staff photographer job at Walker Art Center, as did Szarkowski. At times, Frank’s influence is palpable, as in the homage-like photograph Two women and the flag, Payne Avenue, St. Paul, 1982. Time, itself, has honed Arndt’s eye: he’s become adept at framing the essence of a particular subject, and this talent for distillation is exceedingly evident in the photographs of his native Minnesota. Though ostensibly indiscriminate — whether it is an image of an aging couple with an accordion on a double bicycle, a farmer in a barn of horses, small town parades, Minnesota dragway fans, guys drinking in a dimly lit bar, a carnie at the State Fair, professional wrestlers, or his Aunt Fud’s birthday party -Arndt’s images are, in fact, highly discriminating, visually locking in on the idiosyncratic beauty and irony of the normal.

______________________________________________________

Arndt’s subjects usually inhabit the other side of the socio-economic divide — people whose days are marked by hard work, little luxury, and few breaks.

______________________________________________________

In many instances, Arndt’s images are powerful. Take Man with bow tie, Sixth and Hennepin, Minneapolis, 1975; Freedom, Minneapolis, 1975, Young People, Jordan High School, Minneapolis, 2007; The Perfect Women, Minnesota State Fair, St. Paul, 1973; or Deep Throat, Rialto Theater, Franklin Avenue, Minneapolis, 1974. These photographs are potent not only in composition, but also for the information they contain. In a culture possessed with the attractions of consumption (at least until very recently), whether of things or personalities, Arndt’s work is singularly unconcerned with such things. His subjects are society’s persistently uncultivated; they are anti-bling. Rather, Arndt’s risk has been to find the significance in the insignificant. Underlying these seemingly banal images, a careful viewer can mine a reservoir of information – about the politics of the day, racial tension and harmony, the steadfast hand of poverty, the fruits of hard work, and the power of friendship. Occasionally his images fall flat upon close examination, but rarely.

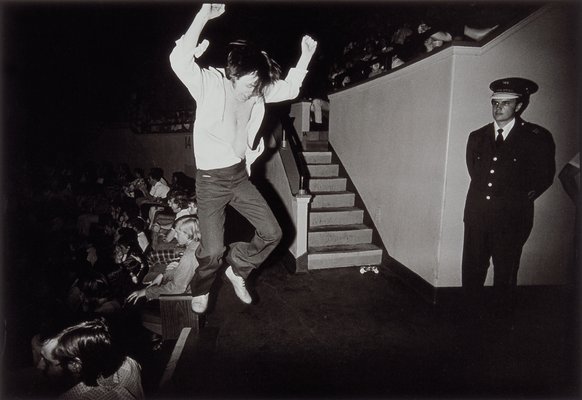

Arndt’s work also exists as an historical portrait of the state, recording the changing dress and habits of Minnesotans over the years and the changing urban landscape of Minneapolis’ Hennepin and Franklin Avenues, or Saint Paul’s West Seventh Place. Viewing Man outside Moby Dick’s, Hennepin Avenue, 1974, who does not mourn the loss of the raucous bar’s seediness or its legendary Whale of a Drink? Is it not a more legitimate face of culture than the current architectural monstrosity occupying Block E, between 5th and 6th Streets on Hennepin? In each image of a rock concert or sporting event, such as Rolling Stones concert, Metropolitan Sports Center, Bloomington, 1972; or Twins game, Metropolitan Stadium, 1975, I search the crowd for familiar faces, even though I did not even live here then. When I saw Leon‘s Dad, St. Paul, 1970, I realized this was the father of my friend, a man who died before I ever met him.

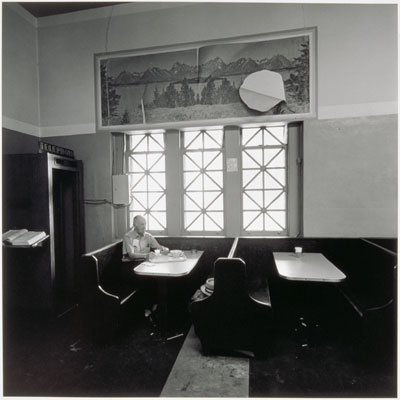

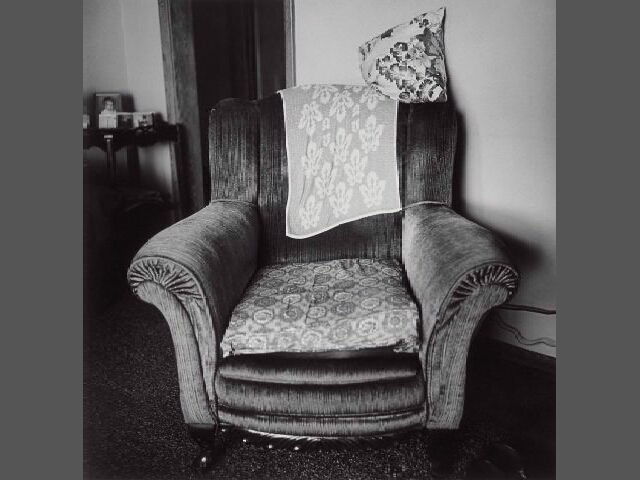

Arndt doesn’t shy away from grittiness, either; his work is often grim. His subjects usually inhabit the other side of the socio-economic divide — people whose days are marked by hard work, little luxury, and few breaks. His subjects’ lives appear more uneventful, even tragic, due to Arndt’s insistence on even grey skies. Seldom are the sun and clouds seen in his exterior images, and his backdrop of dim, uninflected light casts a bald pallor over these scenes. Interiors are stark, illuminated only by emotionally unmanageable light sources – near blinding light shooting through a window into a dark afternoon bar, or motionless figures backlit by a glaring bank of windows. Arndt’s photographs feel hermetically sealed, airless tableaux that allow no emotion. There is not room to exhale. The images are grim and unyielding because what could become sentimental is never given a chance.

______________________________________________________

Viewing Arndt’s photographs is like reading a book, very slowly, isolating and focusing on each word, one at a time. But, in the end there are sentences, paragraphs, stories, and meaning.

______________________________________________________

A subtle but perceptible shift in Arndt’s photographs is evident in his more recent, more composed portraits of young people, athletes, and families. In tenor they are closer to Arndt’s earliest photograph in the show, Family Moment, Minneapolis, 1965. While certainly not buoyant, these recent subjects convey a more positive visage, whether it is Mother and child, Dale and Maryland, St. Paul, 2007; Young people, Jordan Neighborhood, Minneapolis, 2007; or Young couple, Central Avenue, Minneapolis, 2007. In a striking image — Two guys, South High School, Minneapolis, 2006 — two young dudes project the expected cool of their age, but it is a cool seemingly absent of anger or alienation. In the image, there is, perhaps, a little more oxygen in the air.

Arndt’s photographs also reveal how Minnesota, as a state of varying cultural landscapes, has left its own imprint on the world, a visual trail of its activities. Viewing Arndt’s photographs is comparable to reading a book, very slowly, isolating and focusing on each word, one at a time. But, in the end there are sentences, paragraphs, stories, and meaning. Someone voiced the opinion, in a recent discussion, that Arndt’s work was of little merit and that the inclusion of Keillor’s Forward was merely a thinly-disguised publicity stunt. Hearing that, I realized, again, that Arndt’s work is not for everyone. The photographs’ ordinariness can be difficult to embrace or to penetrate. That Keillor and Arndt have been friends for more than 40 years, or that their equally intimate ties to the state have similarly guided their professional careers, were both facts obviously lost on the dissenter.

Tom Arndt’s photographs could be thought of as a visual equivalent to the writing of Sinclair Lewis, another Minnesota native, whose novels Mainstreet (1920) and Babbit (1922), among others, also addressed daily, small-town life in America. In 1930, Lewis won a Nobel Prize; in his Nobel lecture, Lewis expressed regret that “in America most of us – not readers alone, but even writers – are still afraid of any literature which is not a glorification of everything American, a glorification of our faults as well as our virtues,” and that America is “the most contradictory, the most depressing, the most stirring, of any land in the world today.” It would seem that Arndt has substituted Minnesota for Lewis’s America.

*****

Exhibition details:

Tom Arndt’s Minnesota will be on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through August 23 in the Harrison Photography Gallery.

About the writer: Mason Riddle is a critic and writer on the arts, architecture, and design. She is the current president of the Visual Arts Critics Union of Minnesota.