Kitchen Lab: Food as Catalyst of Community and Culture

Heavy Table editor and CHOW.com columnist James Norton digs in to the recent Kitchen Lab residency on the Walker's Open Field, at the intersection of design, public engagement and cuisine, where food and culture meet "collectivist action."

Last Thursday night, under a bright blue sky that faded into a classic summer sunset, guests wandered up a steep green hill into the solemn embrace of the Walker Art Center’s Sky Pesher. In that space was a wooden trunk, practically begging exploration. When they opened the box, guests discovered dried herbs, tea cups, a ceramic pot — a sensory treasure, plants awaiting the alchemy hot water might bring. A young girl, confronted with these raw materials and some enclosed recipes for how to create tea from fresh and dried plants, unexpectedly offers: “I just want to make mine up.” And that’s precisely the kind of free-thinking response to make both a parent and Kitchen Lab designer beam with pride.

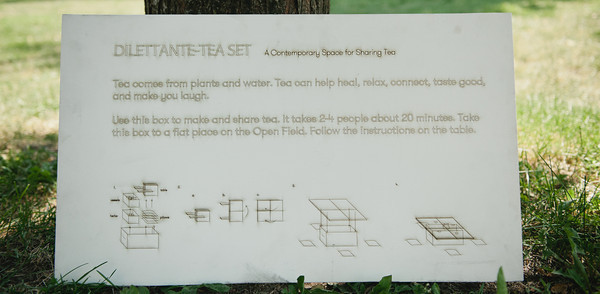

The goal of provoking interaction and discussion through the shared experience of food was central to the Walker’s recent two-week program, “Kitchen Lab: A Mobile Hearth of Collectivist Action.” The series of discussions and workshops was driven by a collective including local educators and students, Walker staff members, and Betsy and Carl DiSalvo, a married pair of scholars from the Georgia Institute of Technology (GIT). In Betsy’s words, the interactive projects culminating from the team’s residency were intended to provide much more than, say, a way to make a beverage; the tea kit, for instance, was created to be a device that could help people explore the way food binds, unites, and divides us.

About the Dilletante Tea Set, Betsy explains further, “The [collective] got pretty playful with it. [We] started to investigate tea culture and what it means to drink tea and… boy, it’s really contentious – who knew? There are strong cultural ties to how people use tea … I think it’s a great demonstration of how food can represent these much greater social ties.” In Asian countries likes China and Japan, tea can (when contrasted with luxe coffee culture) signify unpretentious (or dull and working class) refreshment, just as it signified civilization and upper class aspirations in the West during the heyday of the British Empire.

The tea set, as presented by Kitchen Lab, is open-ended, simple but not impersonal: a collection of cups, a tea pot, a number of dried herbs, an assortment of hand-written recipes and a fold-out tabletop with simple, culturally-unspecified instructions for how to make tea.

In the end, the Kitchen Lab residency on Open Field (running from June 18-29) was many things: A light-hearted meditation on the personal ways we experience food, a vehicle for public discussion, and a way for the DiSalvos to pursue their research — Betsy’s in GIT’s School of Interactive Computing, Carl for the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture.

“We do a lot of projects like this that ask the question: ‘How can you bring together people to create something that wasn’t here before, and do it in a public way?'” explains Carl. In essence, the work of this residency project draws from three nested conversations, all of them complex: The initial conversation between the DiSalvos and the Walker which spawned Kitchen Lab; the conversation between the 14 members of the collective, from which came decisions about bringing in the featured speakers and creating the exhibits that defined the project; and the conversation between Kitchen Lab’s collective and those members of the public who came to explore its tastes, its sounds, and its emergent dialogue.

In addition, “Kitchen Lab brought together researchers, museum staff, educators and students for two weeks to ask: What kind of tools can we build for the Walker Arts Center so they can have food-based arts programming for Open Field?” says Carl. “I’ll take data from a survey we’ll send out in two months to map the relationships that have evolved from this program,” says Betsy. “Who did the participants meet, have they kept in touch with those people, have they reinforced existing relationships?… [I’m trying] to really start a map of the learning ecology around art practice and social practice art.”

That the Lab was comprised of and driven by a group representing a diversity of experience is no accident. “We’ve been inviting in a lot of divergent perspectives,” says the Walker’s Susy Bielak, who serves as associate director of Public and Interpretive Programs. “Part of the work we do at the Walker is [thinking about what] tools foster engagement and participation, especially with Open Field. There are a lot of research goals, but all of the projects that have emerged over this two-week period have participation written into them.”

Weaving together gastronomy, more general sensory and tactile experiences, opera, agriculture, history, and activism over the two-week course of events — the DiSalvos and their collective allowed for many points of public access, but effectively steered a wide berth around controversial issues.

True to mission, last Thursday night’s series-concluding event centered on facilitating public engagement and exploration, driven by miniature, self-contained, interactive exhibits in the form of modestly sized white wooden trunks. It’s easy to see how, broadly speaking, the boxes could serve as prototypes for the sort of interactive exhibits the Walker might incorporate into upcoming seasons of its public art programming.

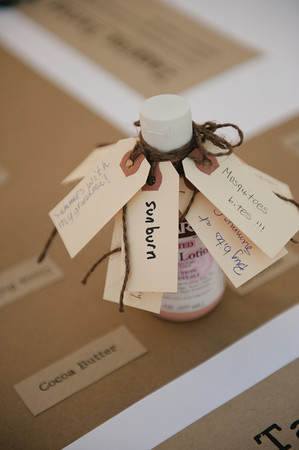

One Kitchen Lab box contained the aforementioned tea kit. Others included a City Pantry “of scents and memories” containing bottles and jars holding strongly-scented foodstuffs; a portable “sink” made from a two-liter bottle, surgical tubing, a bowl, and clamps; a solar oven used to melt chocolate and marshmallows for fondue; and a collection of kitchen curios and ephemera. The appeal of using white trunks as a starting point for the collective’s output is obvious: beginning with what could fit in the box provided welcome limitations to the scope of the group’s goals, but without imposing other hard constraints that would inhibit a creative stream of ideas.

Kitchen Lab’s free-flowing, diverse but unobtrusive approach to programming offered participants a welcoming environment, free of sharp edges — for better and worse. Given the residency’s ambitiously sprawling agenda, qualitative research goals, and soft, open-ended focus, Kitchen Lab’s creators may have passed up opportunities to challenge and engage the audience in favor of gentler experiences and more inclusive conversations. Weaving together gastronomy, more general sensory and tactile experiences, opera, agriculture, history, and activism over the two-week course of events — the DiSalvos and their collective allowed for many points of public access, but effectively steered a wide berth around controversial issues. Even the lab’s tea ceremony, borne of the realization that food can provide cultural challenges and divisions as well as nourishment and camaraderie — avoided specific references to any given cultural practices; even the set’s instructions advise that they constitute merely “one way to make tea.”

Given that questions of food regularly roil the headlines — on inequality of access to healthy fare, controversies over obesity and personal choice, the passage of the Farm Bill, concerns about the safety of genetically modified crops — there was ample opportunity for the series as a whole to dig in aggressively to one or more of these live-wire issues. Kitchen Lab’s experiments could have challenged guests to fundamentally reassess their relationships to food. Instead, the overall program took a more amorphous, genial, and broadly ranging approach.

This kind of inclusivity is, of course, at once a strength and weakness when mounting an ambitious, publicly accessible series of programs with a heterogeneous team, working under a tough deadline: You get many viewpoints, but not much point of view. Or, to use a metaphor more directly applicable to the subject matter, you get many tastes, but not much bite.

One of the most promising aspects of this residency is what it might lead to next, the threads of possibility begun here that might unspool later, in still more meaningful public engagement at the Walker through food — via Open Field or other. similarly interactive programming — mixing the edible, the intellectual, and the soulful. A casual observer couldn’t walk through the Kitchen Lab’s culminating event last week without grinning broadly at the level of invested engagement generated by the project’s various interactive kits. Guests passed objects back and forth, asked questions, described things; they ate, talked together, and generally used the boxes created by Kitchen Lab as starting points to explore and discuss, just as intended.

What’s more, the cross-generational appeal of the exhibits was immediately evident; many attendees brought their children, and those children brought their energy, new eyes, and curiosity to Kitchen Lab’s wondrous assortment of cunning little objects and activities. As a result, on that warm summer evening last week on Open Field, the place hummed with happy noise and purposeful motion.

According to the DiSalvos, future food-driven collaborations with the Walker are in the cards for them, and it will be compelling to see how such projects unfold in the course of time — and almost certainly stimulating to the appetite, to boot.

Related links and information: The Kitchen Lab residency on Open Field at the Walker Art Center ran from June 18 – 30. Read first-hand reports from members of the collective behind these experiments in social engagement through food here, on the Kitchen Lab blog.

Read Sarah Nichols’ and Susy Bielak’s interview with Carl and Betsy DiSalvo for the Walker magazine: “Why Food Now? A conversation on food activism’s moment.”